World

Migration in the Americas: Searching for a better life

Puerto Torro, Chile: Southernmost town in the world

Human migration, the movement of people from one place to another, is an age-old cycle throughout the world. Photojournalist Kadir van Lohuizen traveled from the southern tip of South America to the far reaches of Alaska on the North American continent to explore migration in the Americas. What he found both met and defied stereotypes, which he reported on a website and an app called Via Panam.

Here, fisherman walk the dock in Puerto Torro, Chile, the southernmost settlement in the hemisphere, located on Isla Navarino, just north of Cape Horn. In its last census in 2002, the hamlet recorded just 36 people. A ferry serves the town once a month.

Migrating south to the tip of Chile

Navarino Island attracts labor migrants. Its windswept grasslands are perfect for sheep and cattle ranching. Most inhabitants in this region are from the north. They work as gold diggers or as seasonal laborers in the wool industry, which has become a vital part of the Chilean economy. During the shearing season they travel from one ranch to another to shear sheep.

The arrival of immigrants had dramatic consequences for the native population like the Yaman, the Ona and the Alacaluts, who inhabited these areas for thousands of years. Most of them were killed by the settlers, starved to death or expelled from land that now belongs to multinational companies like Benetton. Only a few communities survived.

Punta Arenas: Finding economic opportunity in prostitution

Prostitutes from the Dutch Antilles in a brothel in Punta Arenas, Chile. The presence of mainly male laborers in industries like ranching and fishing led to the growth of brothels in this southernmost city. Women come from as far away as Colombia or the Dominican Republic to try to make some money.

Attracted by Bolivia's tin industry

The Siglo XX mine in Bolivia opened in 1900, attracting thousands of workers from all over. But after tin prices fell and the market petered out, the government closed the nationalized mine in 1986. The workers formed cooperatives and took it over. Today a few thousand people work again in this mine.

At an altitude of 13,000 feet, with no elevators and no electricity, work in the mine is dangerous and workers’ life expectancy is not higher than 45 years.

•Experience the entire journey, from Chile to Alaska, at the 'Via Panam' website or by downloading the app for iPad. .

Bolivia: Making the most of coca's resurgence

German Almanza and his wife Eusebia Olivera live in Ayopaya, Bolivia, and work as coca farmers. They have three children, one of whom is pictured.

Traditionally coca leaves are chewed, but they are also the most important ingredient in the production of cocaine. For decades poverty-stricken farmers and their families, generally from the highlands, have been migrating to the tropical Chapare area to make a living in the coca fields.

After years of repression, coca farmers were allowed to grow their crops again when Evo Morales, himself a former coca farmer, took office as president in 2006. The government takes a zero-tolerance attitude toward the production of cocaine, but does promote cultivation of coca for personal use such as in tea or traditional medicine.

Peru: City dwellers turn land upside down for gold

Peru is the world’s fifth-largest producer of gold and the Peruvian Amazon contains most of it. The gold rush attracted an estimated 40,000 miners looking for luck, most of them from Cusco.

Protected forest is being turned upside down and huge amounts of mercury are polluting the land and the rivers and endangering people's health.

This is an illegal gold mine in the jungle close to Delta 1, which was once a small hamlet of six houses but now is a town with about 6,500 inhabitants – mostly miners and prostitutes.

Much of Peru’s mining is illegal but the Peruvian authorities do little to stop it.

Peruvians caring for Chile's children

Since the late 1990s Chile has been a popular destination for Peruvian guest workers who can earn more in a week here than they could in a month in Peru.

Many pay the equivalent of a month's wages to get across the border illegally. The Chilean capital of Santiago alone has more than 80,000 Peruvian immigrants. The vast majority are women who leave their own home and children behind to work in the homes and take care of the children of someone else. Almost all the money they earn is sent back to Peru.

Haydee Bercera, 40, works at a household in the outskirts of Santiago. During the week she lives with the family; on the weekend she stays with her sister Norma, who also lives in Santiago.

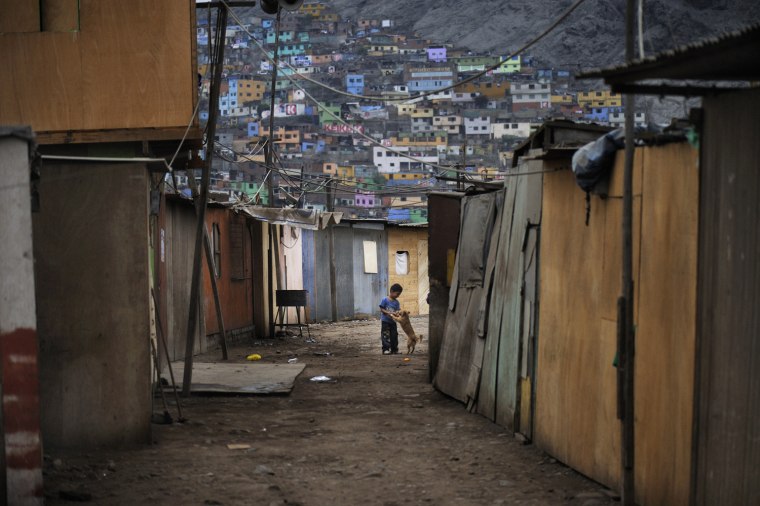

Preserving a way of life in Peru

A boy plays on a street in Cantagallo, Peru. In 1986 the first Shipiba indigenous people from the upper Amazon in Peru came to Lima, fleeing from the Sendero Luminoso (Shining Path, the Maoist guerilla group). They founded the shantytown of Cantagallo in the north of Lima along the Pan-American Highway. Although they’re in a very different environment today, the Shipiba try to keep their culture and language. Women sell their self-made textiles and handicrafts in the streets of Lima.

Bolivia hopes for salt flats windfall from batteries

The Salar de Uyuni in Bolivia is the largest salt lake in the world. The salt layer is at least 130 meters (425 feet) thick. Recently the biggest lithium reserves in the world were found in the salt layer, which could be very promising for Bolivia's future.

Bolivia started a pilot project at the site in April 2011. When the plant goes to full production it will employ hundreds of workers from all over the country.

The Bolivian government has decided that the exploration will stay in Bolivian hands. It is also planning to start producing lithium batteries for electric cars.

Peruvians find work in Ecuador's fields

Telesforo Ventura, 32, in foreground, and his brother Elmer Ventura, 45, work in their rice field.

Elmer came to Ecuador from Chiclayo in northern Peru with his son, his wife and his brother. They are renting the field and hope to start a new life in Ecuador. Elmer returns every six months to Peru to see his family. Many Peruvians migrate to Ecuador to work on banana and rice plantations.

Some work for the owner of the plantation while others have managed to rent their own piece of land.

Black minority among Indian cultures in Ecuador

Ecuador is famous for its indigenous Indian cultures, but it also has a sizeable black minority. A segment of this population has lived far off the beaten path, in the Chota Valley in the Andes of northern Ecuador.

The valley's residents are descendants of African slaves. Tradition has it that a slave ship on its way from Panama to Peru in the 16th century sank off the coast of Ecuador, and dozens of castaways led by a Jesuit priest fled into the mountains. They settled there, creating several black enclaves in the middle of the Quechua Indian population.

Blacks make up about 8 percent of Ecuador’s population. Most of them live in the coastal province of Esmeraldas.

Fleeing Colombia's violence

“The only risk is that you'll want to stay.”

That's the slogan the Colombian government uses in seeking to attract foreign tourists. But for an estimated 3 million Colombians, the situation couldn't be more different. Violence between guerrilla groups, the army, paramilitaries and drug cartels have forced Colombians to flee. Driven from their villages and farms, they end up in the slums surrounding big cities throughout the country.

Twenty-two people, including a family that fled their home after a son was killed by armed men, live in this one-room house.

Every month around 120 Colombians ask for asylum in the border area with Ecuador.

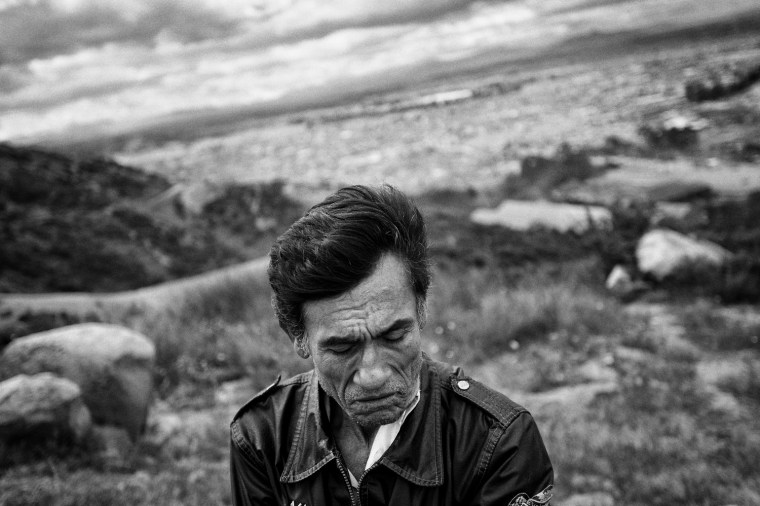

Internally displaced in Colombia

The armed conflict in Colombia has been going on for nearly half a century now. The FARC guerrilla movement and the paramilitaries carry on an unending struggle for the control of territories where there are mines and where coca, the basic ingredient for cocaine, is grown. Some inhabitants of the countryside, often the poor or farmers, are merely in the way. Some are driven off their land and become refugees. It is estimated that Colombia has at least 3 million internal refugees.

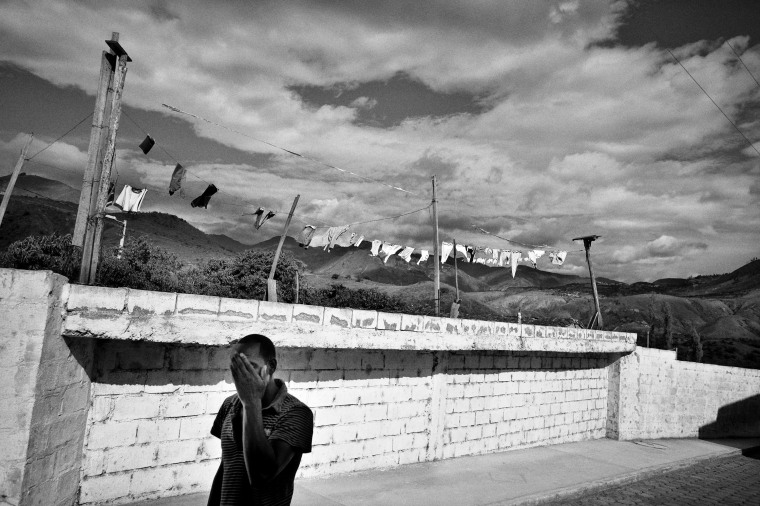

This man is from Barranquilla. He once lived on a farm with his brother. “One day armed men, they were paramilitaries, came and attacked the farm. My brother was killed and I fled to Bogota. I live here alone in Altos de Florida.”

Altos de Florida (Soacha), a suburb of Bogota, has the highest number of refugees in the country.

Fleeing from rising sea levels in Panama

A lobster diver works off Kuna Yala, Panama. The region consists of a long, narrow strip of land and an archipelago of 365 islands, of which 36 are inhabited. Due to the rising sea level, the Kuna, an indigenous tribe, have had to evacuate to the mainland because the islands become too dangerous to live on.

The houses, built of reeds and palm leaves, are no match for storms and rising water. In the past, flooding was comparatively rare; today the residents regularly have to contend with the surging water. In time, they will have to abandon all 36 islands.

Chinese find a home in Panama

Panama is home to the largest colony of Chinese in Central America. The first 1,600 immigrants arrived in 1854 and worked on constructing the first railway connection between the two oceans. In the 1980s, when China opened its borders, a second wave followed. The estimated 200,000 Chinese now living in Panama have acquired considerable economic power.

Here, Susana Ho de Shiao and one of her daughters are seen in the office of Supermercado El Pagoda. They are originally from Guangdong Province, China. Susana came with her grandmother and two brothers in 1984 to Panama. They ran three bakeries before they started Supermercado El Pagoda. They have four children and live in an affluent area in Panama City.

Lured from Nicaragua by Costa Rica's economy

Nicaraguan construction workers in San Jose. Costa Rica has the highest number of immigrants per capita in the world; about 10 percent of the population are immigrants, many from Nicaragua. La Carpio and Tejarcillos are areas in San José where many Nicaraguans live.

•Experience the entire journey, from Chile to Alaska, at the 'Via Panam' website or by downloading the app for iPad. .

Nicaragua: A haven for American retirees

Central America is a favorite destination for moderately wealthy North American retirees.

In looking for quieter and less expensive places to spend their golden years, some have chosen to settle in Nicaragua. It is the second-poorest nation in the Western Hemisphere – but also one of the safest.

Kathy Aley, 64, from Newport Beach, Calif., is among the transplants who have started a second life on the tranquil bay of San Juan del Sur. “I came in February 2001. I need the warmth and the slow life. In the U.S. money and beauty are the power, but I am looking for something else. I left because of the greed and the selfishness in that country,” she says.

From Middle East to Honduras

More than 200,000 of the 6 million people living in Honduras have roots in the Palestinian territories. They are almost all Orthodox Christians, and many hold important positions in trade, industry and politics. The Palestinians in Honduras maintain their Arabic culture, keep up frequent contacts with their families abroad and are very involved in developments in the Middle East. Most have been economically successful and travel back to their homeland regularly.

Here, children play outside the school of Fr. Jorge Faraj, who runs the country’s only Orthodox parish in San Pedro Sula.

Faraj says his grandparents came to Puerto Cortez in Honduras from Beit Sahour, a Palestinian town east of Bethlehem, in 1923. His uncle brought more family members over. “In 1993 we created a school here to preserve the Arab language,” he says.

US influence in El Salvador

El Salvador is often referred to as the most Americanized country in Latin America. It has also one of the highest rates of murders per capita in the world. As El Salvador began to recover from the 12-year civil war, which ended with a peace accord in 1992, U.S. authorities began to deport thousands of gang members to the country, leading to an explosion in gang violence.

Salvador's economy is heavily dependent on “remesas” -- money that Salvadorians in the U.S. send to their families in El Salvador.

Exporting violence and gangs

The Quezaltepeque prison near San Salvador was originally designed for 200 prisoners but currently houses nearly 900. Most are members of two gangs, Mara Salvatrucha, or MS-13, and 18th Street.

When the U.S. stepped up deportations of immigrant criminals in the 1990s, the expelled gang members brought their brutal habits with them to El Salvador, Guatemala and Honduras, countries with weak law enforcement and an inadequate prison system.

Salvadoran family divided

(L to R) Carmen Elena, 26, Irving Ernesto Rosales, 23, Nancy Jasmin Rosales, 15, and their father Ernesto Rosales Guillen, 47, at home in San Salvador. Their mother left in 2005 for Los Angeles to find work, because the family wasn't managing financially.

More than a quarter of El Salvador’s population was displaced by the fighting and many chose to resettle in the U.S. The mass migration began during the country's civil war in the 1980s and continues to this day, fueled by overpopulation and poverty. After the fighting ended in 1992 many of the refugees were sent back to El Salvador, taking American culture with them. Many of the Salvadorans who remain in the U.S., legally or illegally, have also never broken the ties with their homeland.

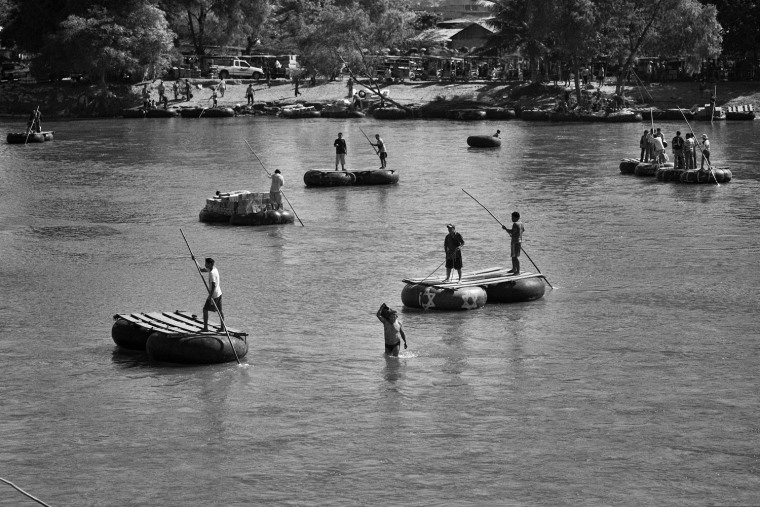

Central Americans move north

Rafts are used to transport local people, migrants and goods across the Suchiate River between Guatemala and Mexico. For Central American migrants, Mexico is the first real obstacle in their journey northward. Mexico requires visas for most and has stepped up border control under pressure from the United States.

Mexico is gateway to US for many

Traveling the length of Mexico is the first hurdle that Central American migrants have to overcome in their journey to the U.S. They cross the country by bus, on foot, or by hitching rides on freight trains. It is a dangerous trip. They run the risk of being coerced by human traffickers. They are regularly robbed and murdered and the females raped as they travel on the margins of safety. Between 100,000 and 200,000 illegal Central American migrants are picked up and expelled from Mexico each year, but many more slip by on their way to the border with the U.S.

Building a border to migration

A new border fence between Mexico and the U.S. is constructed at Douglas, Ariz. The 18-foot fence replaces a much lower one that was less secure. The boundary between Mexico and the United States does more than separate two countries. For many it is the difference between wealth and poverty, hope and hopelessness.

The U.S. has invested heavily in building a secure fence along the border, yet the flood of migration from Mexico continues.

From Mexico to the US and back

Mexican women who have just been deported by the U.S. arrive in Mexico. A doctor treats the blisters on their feet, which many have from walking for days through the desert. The bag is from U.S. Homeland Security and holds their personal belongings. In 2011, the United States deported nearly 397,000 people – the most since the formation of the Immigration and Customs Enforcement agency in 2003.

In Southern California, a mini-El Salvador blooms

Sonia Vanegas Munoz works as a domestic worker in Beverly Hills, Calif., earning $10 per hour. Sonia left El Salvador in 2005 for Los Angeles to find work, because the family wasn't managing financially. She left behind her husband and three children.

An estimated 1.8 million Salvadorans live in the United States, many of them illegally.

Los Angeles and its suburbs are home to more than 300,000 Salvadorans, the largest community from this Central American country in the United States. The migrants, often without residence permits, find work as unskilled laborers; cleaners or nannies for American families in more affluent suburbs.

Iraqis live in America, not always by choice

In the San Diego area there are an estimated 60,000 Iraqis. El Cajon, a town outside San Diego, has the highest number and is often referred to as “Little Baghdad.” Most came here to flee war; the first who arrived were the Kurds during the first Gulf War in 1991. Their numbers rose rapidly after the American invasion of Iraq in 2003.

In recent years more signs in Arabic have been sprouting up along streets for new Iraqi shops and restaurants. The Baghdad Cafe in El Cajon, shown here, is a popular teahouse.

A work force from south of the border

Jorge and Hilda Soto’s children arrive home from school. Jorge came in 1990 from Mexico to the U.S. He worked on a farm in California before coming to the Yakima Valley in Washington state to work on a dairy farm. The Sotos hope to start their own farm one day.

Most Mexican migrants to the United States settle in the border states such as California and Arizona. But some go farther north, and end up in Washington. There they satisfy the demand for cheap labor on livestock ranches and farms growing fruit. On many of the farms almost all of the workers are Mexicans -- some legal residents of the U.S., others not.

Carving out a life in Canada

Canada is acclaimed for its respect for human rights, but in recent years the government has been criticized for doing little to improve the social and economic situation of its indigenous peoples. In February 2012, a United Nations panel questioned why Canada has not made more progress in closing the gap between First Nations communities and the rest of the country.

Trevor Angus, 42, is originally from Kispiox reserve and belongs to the Gitxan tribe. Angus has found success as a wood carver and recently had his first group exhibition at the Vancouver Art Gallery.

In Canada there are more than 630 recognized First Nations governments with a total population of about 700,000 people, of which half live in British Colombia and Ontario.

Making a living at the end of the road in Alaska

About 250 so-called “ice road truckers” travel Alaska’s Dalton Highway each day between Fairbanks and Deadhorse. They bring supplies to the oil companies in Prudhoe Bay.

Deadhorse is the end of the Pan-American Highway at 70 degrees north latitude and 148 degrees west longitude on the coast of the Arctic Ocean. The town’s residents are almost all migrant workers from the U.S. and Latin America who work in the oil fields. The population includes a few dozen full-time residents and up to a few thousand part-timers, depending on oil production.

The oilfields are being leased and are mostly based on native land. •Experience the entire journey, from Chile to Alaska, at the 'Via Panam' website or by downloading the app for iPad.