Donald Trump’s unlikely rise from reality star/businessman to presumptive Republican nominee may seem like a bolt from the blue, but it is directly tied to a long-term demographic trend: The rise of disenchanted blue-collar voters as a force in the party.

The 2016 campaign suggests the power of those voters has reached a critical mass and may be ushering in a remade Grand New Republican Party.

Looking back over the last 25 years of election results, a two-part story emerges for the Republicans: The decline of the party in upscale suburban areas that are becoming more populous and the rise of working-class whites as a force in the party in areas with shrinking populations.

The story can be seen in swing states around the country, including Ohio, where the Republicans are holding their convention this coming week. And two counties in the Buckeye State, Franklin and Monroe, offer some of the strongest evidence of this shift.

Franklin County is home to Ohio’s state capital, Columbus. In the past 25 years, its population has grown from about 748,000 to more than 1.2 million and its politics have moved leftward.

In the 1992 presidential race, Franklin went to President George H. W. Bush by two points. He beat Bill Clinton in the county 42 percent to 40 percent. But by 2012, Franklin went for President Barack Obama heavily. He beat Mitt Romney by 23 points – 61 percent to 38 percent – in the county.

Some 130 miles east, Monroe County sits on the Appalachian eastern border of the state. Since 1990 its population has declined, but its politics have moved to the right.

In 1992, Mr. Clinton trounced Mr. Bush in Monroe – 56 percent to 24 percent. But 20 years later, in 2012, it went for Mr. Romney by 7 points over Mr. Obama – 52 percent to 45 percent.

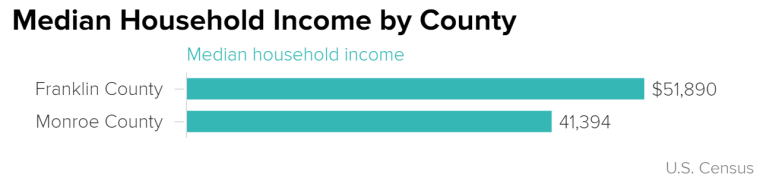

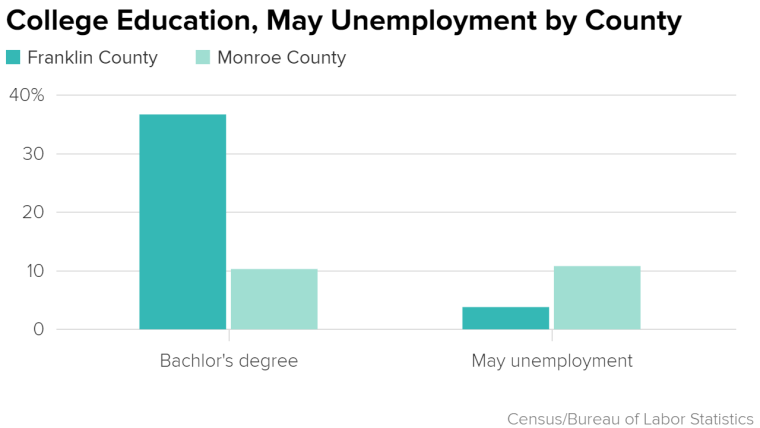

The two counties are remarkably dissimilar in income, education and employment.

Look at those numbers and you see one place that’s doing quite well, Franklin. And one that’s not only struggling in terms of unemployment but that also does not look especially well-positioned to grow, Monroe.

And they voted very differently in Ohio’s March 15 GOP Primary. Ohio Gov. John Kasich won Franklin and its wealthier better-educated voters, with 61 percent of the vote.

Donald Trump trounced the state’s sitting Republican governor in Monroe, 51 percent to 24 percent.

That deep split is at the heart of the Republican’s 2016 fight. It’s also very much about the GOP’s future.

Trump’s campaign relies heavily on the vote of people who have been largely left-behind economically and to some extent culturally. They are voters who believe trade has cost them jobs and who don’t see a bright future ahead.

Monroe is full of voters experiencing that reality. The county is largely rural, but it took a huge economic hit when the giant Ormet Aluminum plant closed for good in 2014.

RELATED: Mike Pence's Traditional Conservatism Cuts Both Ways for Trump

The plant recently employed more than 1,000 people in the area and fed the county’s tax base. It’s now an empty hulk. It’s no wonder that Mr. Trump’s anger, talk of building walls to keep out immigrants and raising tariffs to keep out imports resonates in Monroe and places like it.

But the story is very different in Franklin, which thrives in the 21st Century knowledge economy. Columbus, the state capital, ensures there are jobs for policy experts, lawyers and lobbyists. And Ohio State University is a big institutional employer that works with the research and technology sectors. In fact, throughout the last recession and the recovery, Franklin was consistently below the state and national unemployment averages.

That’s not a great environment for Mr. Trump’s message. The county is not “losing” in the new economic reality. It’s one of the “winners.” Even the bad times for the U.S. economy don’t feel as bad in Franklin – and the current times feel pretty good.

This divide between voters in the “Franklins” and the “Monroes” is at the heart of the GOP’s political earthquake in 2016.

Franklin and counties like it are big, densely-populated metropolitan hubs. They are where the voters are – and they are growing. You need to win a lot of places like Monroe and drive up the vote in them to extremely high levels to make up for every Franklin you lose.

In short, the GOP needs better showings in the suburbs if it’s going to win statewide and national races.

That’s why the 2016 campaign right now is about a lot more than just winning the White House for the Republican Party. It’s about where the party is headed in 2017, 2018 and all the years after.

We’ll be devoting more time to what these changes mean for the GOP in the days and weeks ahead, but for now the broader message is “this is not your father’s Republican Party anymore.” It been shifting over the past two decades and 2016 may be the year the sliding tectonic plates created the earthquake that remade the party.