Fazul Rahim is a reporter and producer with NBC News in Kabul. He will be joining the United Nations next month. Here he reflects on the anniversary of the 9/11 attacks that triggered the invasion of Afghanistan, and why, in spite of everything, there is reason to hope.

KABUL — My littlest, Maryam Setayesh, was born on Sunday — a full three weeks late. The children at home were delighted, and her birth was met with raucous celebrations.

Her older siblings weren’t planned, but my wife Fatana and I thought carefully before having a sixth. So in spite of my wife’s cesarean, the birth was the most joyous moment of our lives.

But within hours of her delivery two attacks tore through Afghanistan’s capital, killing 41 and forcing me to question our decision. I asked myself: Why had I taken responsibility for another life in this messy corner of the world?

It would be easy for me to sink into despair now, 15 years after the Sept. 11 attacks that triggered the U.S. invasion of Afghanistan and lifted the expectations of millions of my countrymen.

Related: Full coverage of the 9/11 anniversary

These are the reasons to despair.

When the Americans launched the war here on Oct. 7, 2001, Afghans throughout the country hoped this spelled an end to two decades of war and misery. But it hasn’t turned out that way — and the Taliban now controls more territory that it has since its ouster.

Kabul — long an oasis of relative calm — is increasingly under attack. The government is divided and riven with corruption. Many Afghans have given up hope and we now make up the second-largest group of refugees trying to get to Europe.

Monday's blasts came almost two weeks after gunmen attacked the American University of Afghanistan in Kabul and killed 14 people — truly the country’s best and brightest. Some of those killed were close friends.

It was one of the hardest stories I've had to report in my 15 years as a journalist here. I graduated from the school last year with high hopes and infinite optimism for the future. And on Monday, I found myself reporting on an institution that had become a second home for me — while also texting and calling friends who were trapped in classrooms. Some did not make it; others are still in the hospital.

But after a sleepless night I chose joy over despair — not for the first time.

One of the things I find fascinating about my country is that no matter how seemingly difficult the situation, we seem to get back to normal fast.

That is probably a good trait, and one I’ve had to employ many times.

I used it during my childhood when war forced my family from its home 12 times before I finished high school. I needed it when I lost my childhood best friend Younis to a stray bullet in Kabul. I employed it during multiple mortar attacks on my house.

It was there when three Uzbek militiamen beat and tried to kidnap me as I walked home from school. I don’t know what they wanted — maybe it was because I was Tajik and from another ethnic group. They may have wanted to kill me. Maybe they wanted to rape me.

But I was saved when a rival militiamen found us and forced the gunmen to hand me over.

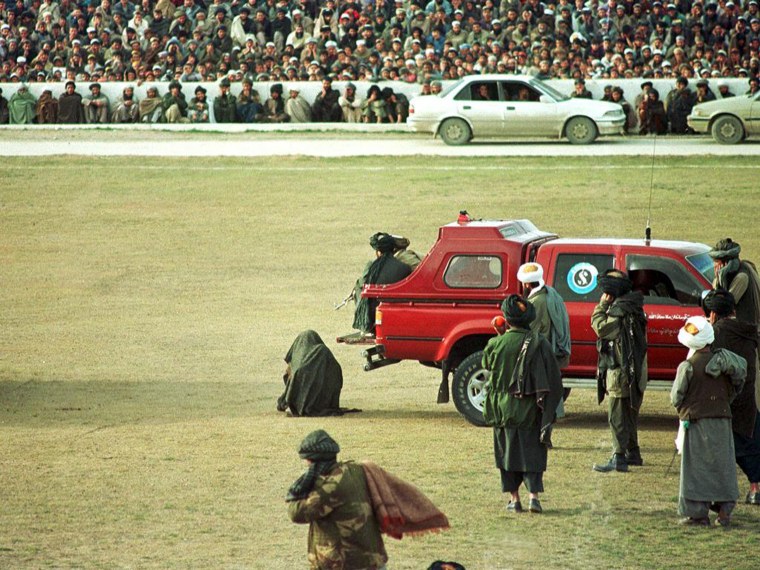

I needed my resilience when I spent three nights in a Taliban cell a couple of weeks after the militants swept into Kabul on Sept. 27, 1996. Some of us hoped these “Islamic warriors” would impose peace on a country torn apart by war.

But as fierce men in turbans and shaggy beards beat me with electricity cables and demanded “Where are the weapons? Where are the AK-47s?” I did lose hope in them.

Then I was thankful for freedom when a family friend helped buy my release.

"We underestimated the Taliban’s resistance"

So I survived high school and was admitted into medical school. This was huge deal — like going to Harvard — and I was overjoyed in spite of the fact that around me the Taliban was raiding homes and taking people to jail. Life was looking up!

But my medical career was cut short in 1998 when a classmate took me aside and said: "Don’t go home — if you go out that gate they will catch you."

"They" were a gang of Taliban with a list of 15 students to be rounded up — my name was No. 2.

I managed to escape and stayed away from Kabul for a year-and-a-half, but snuck back once to get married to Fatana in 1999.

I took my bride back to my family's village in Panjshir Valley, an entirely Tajik area surrounded on three sides by the Taliban.

Life was tough, but our expectations were very low. So in spite everything, we were happy. At first I mined emeralds but soon I was asked to teach at the village school. There was an opportunity to launch English classes in the village for kids whose only educational options before had been through mosques or religious texts.

The remote and conservative community welcome the new opportunities, though the local mullahs didn't like it and some began preaching against my classes.

So, I invited 20 or so to come by told them: “Show me a religious fatwa that says ‘English is against Islam' and then I will stop the classes.”

They couldn’t show me — so I didn’t end my classes.

A moment of true despair came on Sept. 9, 2001 — two days before the 9/11 attacks on the U.S. — when Ahmad Shah Massoud, the anti-Communist leader leading resistance against the Taliban, was assassinated by al Qaeda. I can honestly say his funeral was the saddest day for us.

But the realization a few days later that al Qaeda — which was being sheltered by the Taliban — had attacked the U.S. brought us hope.

“This might have some effect on us,” people said. “If Taliban are involved in this attack, America is going to do something about it.”

People knew Stinger missiles very well — the U.S. weapons had helped defeat the Soviets 15 years earlier. They knew the might of America. So there you go: More hope and resilience in the middle of despair.

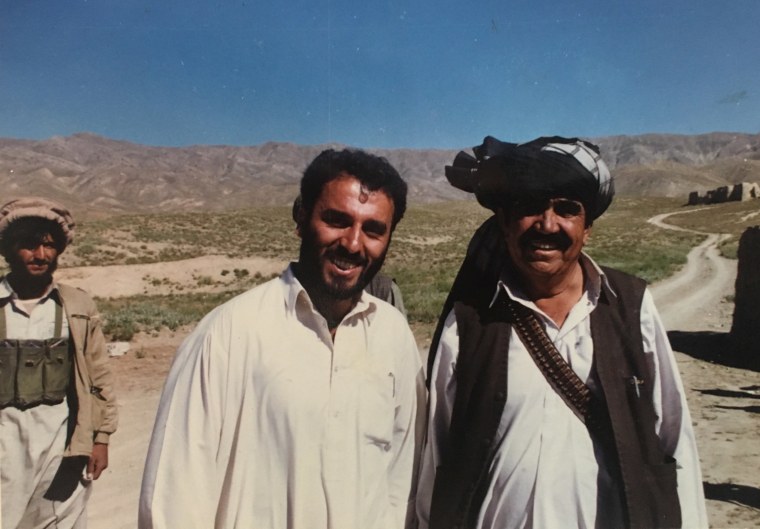

Soon life began to move very fast. Foreigners began to flood into Afghanistan — not soldiers, but journalists. They brought more money than any of us had ever seen. I began working for them.

When the U.S. launched airstrikes on Oct. 7, 2001, we thought our bad days are over, that the Taliban was done and Afghanistan had started a new chapter. We were certain it was the start of a new era of peace, prosperity and stability.

But things have not worked out that way.

We underestimated the Taliban’s resistance, and neighboring countries' desire to meddle in our affairs.

Related: As U.S. Draws Back, Afghan Women's Future in Doubt

We did not count on the alienation that many Pashtuns felt — the Taliban is a predominantly Pashtun movement and many did not feel part of the “new” Afghanistan.

Finally, we couldn’t foresee the invasion of Iraq in 2003, and America turning its attention away from Afghanistan.

So I’ve decided I’ll always be ruled by hope and worry.

The hope I feel is lodged in the new generation — the young people who have been exposed to ideas and the world. Nobody can turn back the clock on them.

My little Maryam is one of this new generation. And for her it is my duty to hold out hope for Afghanistan.

— As told to F. Brinley Bruton