On birthdays and holidays, Russell Mercer and his family gather around a small stone at Mount St. Mary Cemetery near their home in Queens, New York. Etched into the slab is the name of his stepson, Scott Kopytko, a firefighter who died in 9/11.

The marker reminds them of the man they lost, but also what is still missing.

There is no grave underneath, because no trace of Kopytko has been found.

Related: Full coverage of the 9/11 anniversary

"If you have remains, you know that he came back to your family. You know a place you can stand and talk to him," Mercer, 69, said. "But I'm talking to the wind, that's who I'm talking to. There's nothing there."

Fifteen years after the attacks on the World Trade Center, the remains of 1,113 victims — 40 percent of the 2,753 who died — still have not been identified.

That absence of physical evidence agonizes many 9/11 families.

Some describe the missing identifications as equivalent to a great vanishing, similar to the thousands lost in the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami, or the disappearances of political dissidents in Argentina's Dirty War.

The victims are undoubtedly dead, but there is no bodily proof.

The void is like a ghost, "intangible, lingering, the opposite of something that is concrete and tangible," said Chip Colwell, senior curator of anthropology at the Denver Museum of Nature & Science who has advised families of 9/11 victims. "That leads to ongoing pain and suffering for many of these families."

Remains are a key part of the grieving process, giving mourners something specific to remember the person they've lost, Colwell said. They are symbols — something to visit and make part of a routine.

Many of those whose loved ones have been returned to them have found a level of closure that many of the others have not.

The identification process itself has been tumultuous: called off in 2005 due to the limits of DNA technology, only to be restarted a year later, when the discovery of more remains triggered a new search effort that uncovered even more. Families unsuccessfully tried to block the city from moving trade center debris to a landfill, arguing that the material could contain body parts. Later, additional remains were found amid freshly removed debris.

The need for something physical to mourn has driven some families to find unorthodox alternatives. That includes the case of Lawrence Stack, a New York Fire Department chief who donated blood — part of a bone marrow drive for a child with cancer — before perishing in the towers' collapse. His family discovered the vial. In June, they held a proper Catholic funeral Mass.

Other families say they choose to believe that their loved ones are among the unidentified remains stored at a repository underneath the World Trade Center site, adjacent to the 9/11 Memorial Museum. Instead of a grave or crypt or urn, these families visit the site's "reflection room," where they find some level of comfort.

"This is a place I have to go, because that's where they took their last breath," said Monica Iken-Murphy, whose husband, Michael Patrick Iken, died in the trade center's south tower. "That was the only place I felt connected with Michael. Others feel the same way; they have no other place to go."

She held a memorial service for her husband at St. Patrick's Cathedral a month after the attacks, and became a vocal advocate for 9/11 families, even as she remarried and had two daughters. She founded two preschools named after her first husband. And she became an active proponent of the museum and repository, which opened in 2014, arguing that it could serve as a monument for those who had nothing.

"I wanted to make sure their remains were at a final resting point," Iken-Murphy, 46, said. "Even if they're not identified, they're still there. I get solace there. I can go any time. And that has helped the healing process."

Charles G. Wolf has also found peace at the repository, where he stops at the name of his wife, Katherine Wolf, who died in the north tower, and remembers her as he would at a gravesite.

He marked her death in October 2001 at the Cathedral of Saint John the Divine, but struggled for years as he longed for a part of her to turn up. The vacancy still hurts, but the repository makes him feel more connected to her, he said.

He visits the site several times a year, including her birthday and July 4 — and the anniversary of the attacks.

"I don't know if any of Katherine is in there," Wolf, 62, said. "But I walk into that museum and I feel like it's partly mine. There's a feeling of ownership."

He hopes that one day his wife's remains will be identified — so he can put them in a niche at St. John the Divine. "I don't wait for it. I don't expect it. If it happens, I'll deal with it," he said.

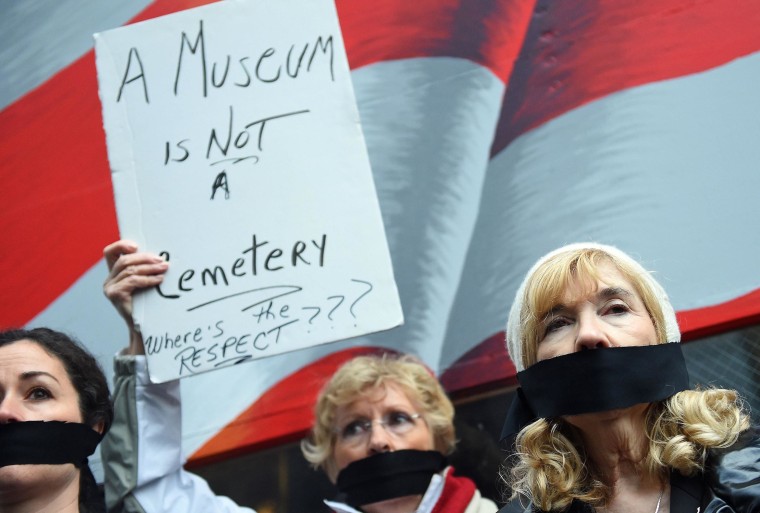

But there are many families who fought the city's decision to move the remains to the repository. Some of them say the unidentified dead deserve an above-ground memorial like the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier in Arlington National Cemetery — separated from the museum, which they call crass.

Sally Regenhard is among them.

Her son, Christian Regenhard, was a probationary firefighter who died responding to the attacks.

Keeping remains at the repository is painful and insulting, she said. "The room has no sanctity, no religiosity, no atmosphere or respect like an interfaith chapel would."

Unable to find peace there, Regenhard, 69, said she remembers her son by keeping portraits, mementos and posthumous medals in her living room.

Her grief would be different, she said, if there was something of him.

"There's an unreality. There's a feeling you can't accept what happened because you have no tangible truth of what happened," she said. "It's very disappointing. Devastating. Depressing.

"It's a pain in your heart that you constantly live with."

Mercer, too, opposes the repository and museum. But he also considers himself fortunate to have places that memorialize his stepson: the cemetery stone, and a small piece of land at a three-way intersection near the family home that has been renamed in his honor. He keeps the plot clean and outfitted with American flags, and explains its meaning to curious passersby.

He believes that one day his stepson's remains will be identified.

"You have to be positive," Mercer said. "If you don't, you're going to drive yourself crazy. Maybe it won't happen in my lifetime, maybe my daughter will get it. But I think they will find him."