Daddy was coming back, of that Wyatt Paterson was certain. Wyatt didn’t know where his dad was, exactly, but he knew his faith would be rewarded.

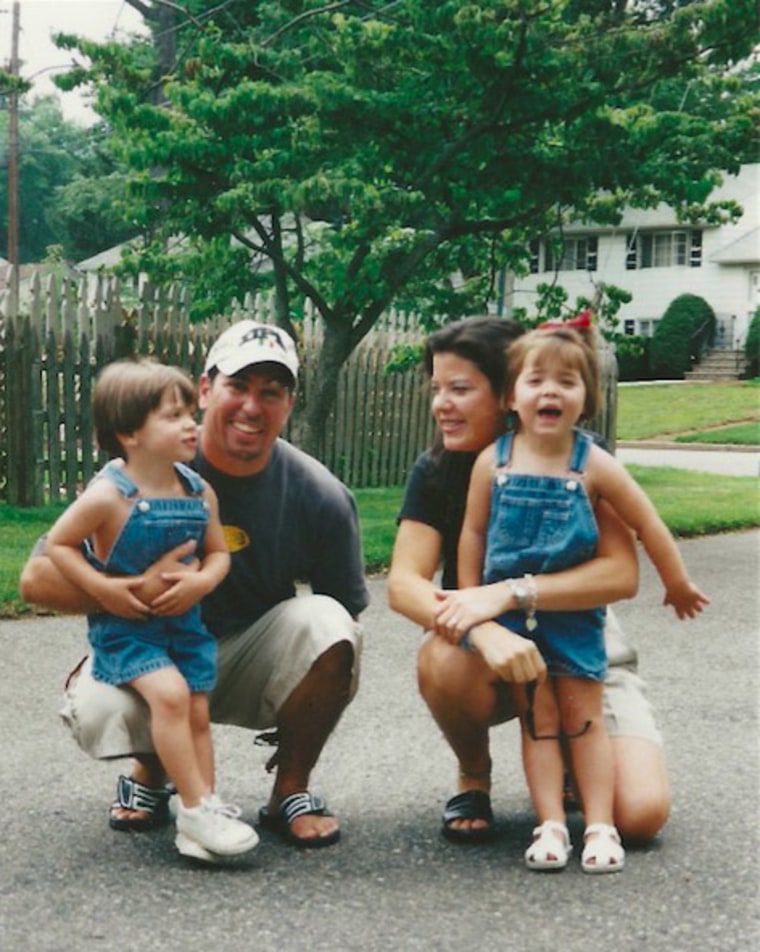

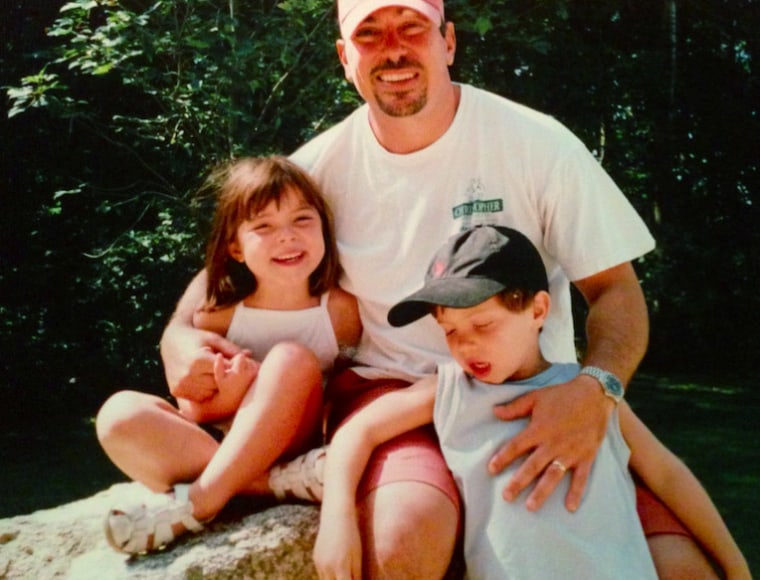

Wyatt, who is developmentally disabled, and his twin sister Lucy were 4 years old when the World Trade Center towers fell, killing their father, Steven, and thousands more. After September 11, Wyatt began to sit and stare out the window of his New Jersey home at the same time his father had always returned home from work.

Through the U.S. invasion of Afghanistan, the passage of the Patriot Act and Osama bin Laden’s Houdini act at Tora Bora, Wyatt took up sentry there. Through President Bush’s “Axis of Evil” speech, the establishment of the 9/11 Commission, and the invasion of Iraq, he held vigil. It was not until the spring of 2003 — around the time Bush was landing on an aircraft carrier to declare “Mission Accomplished” in Iraq — that Wyatt gave up his post. His doctors would eventually diagnose Wyatt with the worst case severe post-traumatic stress disorder they'd ever seen.

Related: Unidentified Remains Leave a Lingering Void for 9/11 Families

Wyatt's twin sister Lucy's sole memory of that time is of her mother Lisa and a few relatives gathered in Wyatt's room, the pall that would hang over them all for years already cast. Lucy's reaction was markedly different from her brother's. She tucked the news away, engrossing herself with friends and play. As workers at Ground Zero began to sift through the rubble that held her father’s remains, Lucy was compiling her own prodigious mound, entombing her pain beneath it. Behind her happy-go-lucky facade, she was struggling to fill the void left by her father’s death.

Lisa Paterson probably “shouldn’t be here.” That, at least, was the conclusion drawn by the doctor tasked with assessing the scope of the psychological damage inflicted by the tragedy-piled-upon-tragedy arc of her life. She was abandoned by her biological mother, then adopted into a loving home - only to be left fatherless at age 11. As a teenager, she lost her brother to drug addiction and a subsequent overdose. After her husband's murder, she was forced to raise her young twins as a single parent, unable to pull her son from the chasm of his grief.

“People with a lot less trauma often end up either in prison, or with a serious drug addiction,” says Dr. Richard Guild, Lisa’s psychologist for more than a decade.

That the Patersons survived is a testament to the near infinite capacity of the human race to endure suffering, but also to hope. That they thrive is due in no small part to the vow Lisa made a few days after the towers fell. “This will not break me,” she swore to herself. She simply would not allow the same fighting spirit that had first attracted Steven to her to die alongside him. And she would not allow the men responsible for the attacks, who had already taken so much, to hold her children captive in despair.

“My job,” she says today, “was not to let those terrorists ruin my kids.”

More than 3,000 children lost a parent on 9/11. And while the traumas inflicted on other family members and first responders was no doubt felt as deeply as any, for the children of 9/11, theirs is a distinct kind of pain.

“It’s not a badge of honor," says Terry Sears, executive Director of Tuesday’s Children, the response and recovery support organization formed in the aftermath of 9/11: “It’s almost like ‘I’m different,’ and no kid wants to be different.”

While not a mental health professional, Sears has observed a complex layer of emotions in these children and young adults. Parents and professionals are not always able to easily discern what is normal adolescent behavior, and what is attributable to 9/11. The high-profile nature of the event, Sears says, is also a contributing factor. Dr. Abba Cargan, Wyatt Paterson’s pediatric neurologist since he was an infant, concurs: “I don’t know if there’s anything comparable — most people don’t have their trauma broadcast day in, day out.”

“If your first real view of the world is your parent being murdered, it’s very hard to put that in its place,” Sears says.

For a developmentally disabled child like Wyatt, it would prove to be spectacularly difficult.

By the age of two, Wyatt had taught himself to ride a scooter and routinely batted balls all over the house — a skill that thrilled his sports-obsessed father. But he was also exhibiting worrisome signs of impairment. His speech development lagged behind that of Lucy’s and other peers. He would throw tantrums for seemingly no reason. His doctors were quick to rule out autism, but his symptoms perplexed them.

In early 2000, Wyatt suffered the first of two grand mal seizures. One night at dinner, his head suddenly dropped forward into his dinner plate; an atonic seizure common in epileptic children. His doctors eventually managed to get the seizures under control, but the hundreds of epileptic episodes he suffered in the interim had left him with irreversible brain damage.

A few days before 9/11, the Patersons were enjoying a family day at the beach, and Steven was feeling especially hopeful about the future. Wyatt had been seizure-free for months, and after a long legal battle with the school district, he was about to join his sister at preschool. Steven assured Lisa that everything was going to be OK.

“Do you trust me?” Lisa remembers him asking that day.

“Yes,” she affirmed.

The morning of Tuesday, September 11, 2001, was clear and bright, a gorgeous late summer day in the New York area. Steven had been sick with a fever and headache the night before, and sleep had done little to help. Despite Lisa’s protestations, he dutifully trudged in to work.

His job as a trader for Cantor Fitzgerald was a demanding one, and mornings were especially busy. Steven called when he got to the office around 7:30 a.m., as he always did. He gave Lucy and Wyatt pep talks about their second day of school, and talked about what games they would play that night.

When the phone made its way back to Lisa, she asked how he was feeling. “Worse,” Steven conceded, finally agreeing to leave around lunchtime, and to stop and see his doctor on the way home. He asked Lisa to have his watch repaired — part of a matching set they had picked up on their honeymoon.

“I love you,” Lisa said just before hanging up

“I love you,” Steven replied.

Those were the last words they would ever share.

Lisa left the house minutes before the first plane struck the North Tower, where Steven worked. His watch was strapped to her wrist beside her own as a reminder to drop it off for repair. It would be a year before she could bring herself to take it off.

Shortly after she got the kids to school, the radio station had breaking news of a “small plane” striking the World Trade Center. Back at home, she tried calling Steven at the office, and got a strange busy signal. Then she turned on the TV, and began to scream.

Her husband’s death was overwhelming, ruinous, final. But it would also reveal other traumas long left untreated. Lisa calls her abandonment as a day-old baby “the initial wound that has tempered everything in my life.” She was tormented by imaginings of Steven’s final moments.

“I hated the idea that he thought, ‘Oh my God, her worst fears are coming true. I’m leaving her,’” Lisa said.

Before she could tend those wounds, however, there was the not-so-small matter of tending to her four year-old, now fatherless twins.

Related: Obama on 9/11: 'Americans Will Never Give In to Fear'

Wyatt’s mind was simply incapable of fully processing his father’s absence. He would fixate on photographs of Steven, begging him to come back. Placing them on the floor, he would try and jump into the photographs to join him — much as he’d seen done with sidewalk chalk drawings by the characters from a favorite movie, “Mary Poppins.” He would ask for his father dozens of times a day, every day.

“He didn’t have the same understanding another child would have had regarding 9/11,” Cargan, his pediatric neurologist, says. “All of the emotions are in there, but his ‘news feed’ is different than ours.”

When nothing brought Steven back, Wyatt would have regular, often epic tantrums. Lucy, an otherwise patient child, would sometimes default to her own screams: “Make him stop! Make him stop asking!” All of this went on for nearly a decade.

With hindsight, Lisa observes that Wyatt mourning “so openly and furiously and without inhibition, the way we all wish we could when someone we love dies,” helped pave the way for her own eventual emergence from grief, and Lucy’s.

“There’s a bit of, ‘Get over it already, it’s been ten years, it’s been fifteen years,’” says Guild, Lisa’s therapist, alluding to a small but stubborn refrain regarding victims of 9/11. That sentiment was amplified by a 2006 book written by the right-wing political commentator Ann Coulter, in which she wrote of the widows who pushed for the creation of the 9/11 Commission: “I have never seen people enjoying their husband’s deaths so much.”

Related: 'The Forgotten 9/11': Returning to the Pentagon 15 Years Later

Lisa has observed another disturbing pattern with regard to victims of 9/11. “Some teachers don't understand why the 9/11 kids are still grieving, or just starting to. These kids weren't living it in real time, necessarily, and now their young brains are trying to process it all,” she says.

For years, Lisa sent a form letter to Lucy’s teachers, changing only the name and date, informing them that there was a 9/11 child in their classroom.

“School should be a safe place for me,” Lucy contends. She recites a series of wrenching incidents throughout grade school: A third grade teacher who had pinned a photo of the twin towers up in the classroom, a classmate who taunted her because her father had died on 9/11, and a senior year high school teacher who had the class watch a video on PTSD, complete with scenes from the worst day of her life.

As her children came of age, Lisa did her best to dole out information about their father’s death in an age-appropriate way, parsing what she knew into little bits of emotionally digestible pieces. “Lucy was probably ten years old,” Lisa says, “when she very pointedly asked me, ‘What happened to Daddy in that building?’ How do you tell them that the boogeyman is real?”

As a high school student, Lucy took part in “Project Common Bond,” a Tuesday’s Children program for young adults who have lost family members to terrorism or violent extremism.

“Everyone focuses on 9/11 because it’s an American tragedy,” Lucy points out, “but there are people from all over this world who have this common connection.” She is pursuing a degree in studio arts and psychology, and is thriving. But that September day still casts a long shadow.

“I consider myself a very happy young adult," she says, “but it chipped away a little piece of me. It’s almost like losing a limb, and having to relearn everything you knew before.”

For her twin, Wyatt, reaching that final stage of grief — acceptance — took nearly a decade.

“Grief is not something you ‘get over,’” Lisa insists. “It’s something you go through.”

Wyatt’s neurologist says the entire process was different for Wyatt.

“He sort of bought into his own script to finally understand that his father wasn’t coming home," Cargan says. "As horrific as this whole experience has been for him, he hasn’t been soured by it. He’s still trying to enjoy life, and to move forward.”

What helped Wyatt’s transition was finally finding a place, after eight schools and countless therapists and unsuccessful methods, that allowed him to blossom. That place? A working farm in Pennsylvania that caters to intellectually and developmentally disabled (IDD) adults. The farm is an example of an “intentional community” designed as a cooperative with a common purpose, and of the kind of place advocates say the U.S. needs more of to address the rising number of adults with special needs. The first time Wyatt walked onto the farm, the dogs flocked to him, and he’s never looked back, Lisa says.

Asked why he liked it there so much, Wyatt floored his mother with his reply: “Daddy’s in the sky there.”

Lisa is moved by the author Brene Brown’s summary of the healing process: “When we deny our stories, they define us. When we own our stories, we get to write the ending.”

She is writing hers in part by helping students write their own beginnings. Motivated by a private conversation with President Obama at Ground Zero after Osama bin Laden was killed, she started her own business helping high school kids with college essay writing and other writing workshops.

Just this week, Wyatt began life at a new farm in Duchess County, New York, one that Lisa hopes will be a long-term home for him. Securing Wyatt’s future has been a source of near-constant anxiety for her, but she worries too about other victims of 9/11 who have fallen through the cracks.

"There’s this feeling that kids are so resilient, and I don’t think that’s necessarily the case," Lisa says. "What they don’t realize is that the only way through grief is by telling your story, and having it heard.”

She has forged the kind of life with Lucy and Wyatt of which she knows Steven would be proud. She points to this Jackson Browne lyric as a template for her post 9/11 world:

"Forget what life used to be/You are what you choose to be/It's whatever it is you see/That life will become."

"That's me after 9/11, says Paterson. I've chosen to create the life I want."