In the search for the missing AirAsia Flight QZ8501, the Indonesian government can call on an array of devices and technology that may help find the jet that disappeared from radar Sunday with 162 people on board.

The technology ranges from beacon locators to long range aircraft to submersibles, but the longer they wait to use them, the more difficult the search will become, experts say.

Early reports indicate that the AirAsia plane disappeared in a stretch of the Java Sea that is only 130 feet deep, on average, versus the 13,000 feet depth where Malaysia Airlines Flight MH370 -- which disappeared in March with 239 people on board -- likely went down.

"Just because it's shallow water doesn't make it a cakewalk," David Gallo, director of special projects at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, told NBC News.

"Just because it's shallow water doesn't make it a cakewalk."

Planes that crash underwater are often found with beacon locators, devices that are dragged underwater by ships looking for pings from the plane's Underwater Locator Beacon. In shallow water, tidal currents can distort those pings and make smoothly dragging the beacon locators a challenge.

"If the currents are strong, it makes it very difficult," Gallo said. For the planes circling above, visibility in shallow water can be poor thanks to sediment from the nearby land.

On the plus side, the Java Sea is filled with ports, which makes access to the potential crash sites easier for search teams.

Indonesian authorities told The Associated Press that it has 12 navy ships, five planes and three helicopters searching for the missing jetliner. Singapore has committed two C-130 jets and two beacon locators to the cause. Australia and Malaysia have volunteered resources too.

Indonesia has not requested help from the U.S. Navy's Seventh Fleet, according to a Navy spokesperson. The fleet used infrared camera-equipped MH-60R Seahawk helicopters and a P-3 Orion aircraft, which can fly for nine to 10 hours straight, to search for the missing Malaysia Airlines plane.

The Seventh Fleet said in a statement that it would "stand ready to assist in any way that's helpful."

Singapore said on Monday that it would volunteer a robotic submersible. So far, no other countries have committed submersibles to the search.

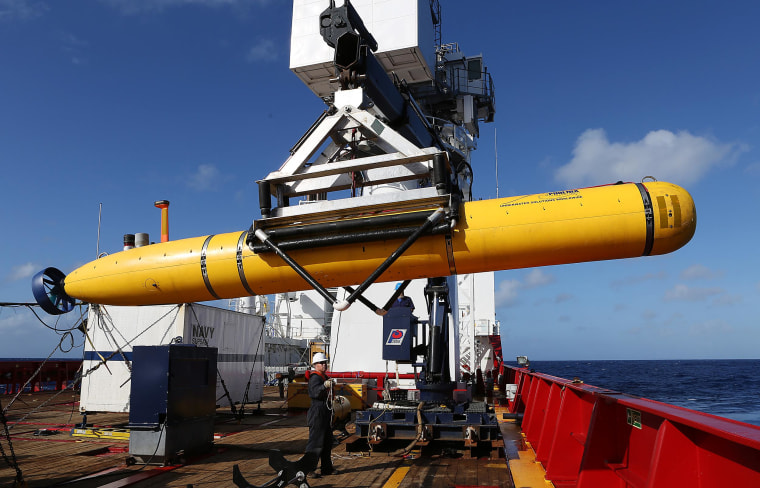

The U.S. Navy-owned Bluefin 21— which is capable of providing recorded video footage and 3-D sonar maps of the ocean floor — was used in the search for the missing Malaysia Airways jetliner.

Another option is a submersible like the U.S. Navy's Orion, which can descend 20,000 feet and provide live video from the depths of the ocean.

Submersibles

Even though the Java Sea is not deep, the search could benefit from the use of submersibles, Gallo said. He pointed to the Remote Environmental Monitoring UnitS, or REMUS, which are small drones ideal for searching shallow waters.

Their size means that multiple drones can be launched from a single boat, which is makes them convenient for covering large swaths of ocean. The search area in the Java Sea stretches 120,000 square miles, or about the size of New Mexico.

The region's recent stormy weather and sediment dredged up by tidal currents could make spotting signs of wreckage from above — whether from aircraft or satellites — much more difficult.

When a commercial plane crashes, its emergency locator transmitter (ELT) should automatically turn on, broadcasting a signal that can be picked up by passing airplanes. The problem? They can sometimes malfunction, especially when involved in a violent crash.

It's also hard for airplanes and satellites to pick up the ELT signal when the downed plane is underwater, former National Transportation Safety Board investigator Greg Feith said on TODAY after the Malaysia Airlines jetliner went missing.

That is why submersibles are so important, Gallo said. Overall, however, it's the leadership behind the search that will make the biggest difference. Every wasted hour means a growing search radius, as currents carry debris away from the original crash site.

"It's almost like an orchestra," Gallo said. "You can have the right instruments, but you need the right talent and organization to make it work."