The worst part for registered nurse Anja Wolz is when the children come in. She wants to comfort them, but it’s almost impossible to cuddle a child when you’re wearing a full body suit, a hood with a visor, two pairs of gloves and rubber boots.

Wolz, emergency coordinator for Medicins Sans Frontieres (MSF or Doctors Without Borders), is working at one of her group’s emergency care centers in Sierra Leone, where more than 900 people have been infected with Ebola and where about 400 of them have died.

“It’s the children who distress me most,” Wolz writes in a commentary published in the New England Journal of Medicine. “In the confirmed-case tents, I cared for a 6-year-old boy and his 3-year-old sister. Their parents and grandmother had died from Ebola,” she writes.

“When the boy died, we tried to console and calm his sister, but the PPE (personal protective equipment) made it difficult to touch her, to hold her, even to speak with her. She died the next day.”

“It’s the children who distress me most."

MSF and the World Health Organization agree that the Ebola outbreak in West Africa is out of control, getting worse, and that there is not nearly enough help. More than 2,600 people have been confirmed infected and more than 1,400 have died, but WHO and MSF both also say that the official count is far less than the actual numbers.

Many people are dying and never being counted. “Every day sees deaths in the community that are surely caused by Ebola, but they are not counted by the Ministry of Health because the cause has not been confirmed by laboratory testing,” Wolz writes. “We need to be one step ahead of this outbreak, but right now we are five steps behind.”

MSF has started expressing outrage.

“In its first week, MSF’s Ebola newest management centre ... in the capital Monrovia, is already at capacity with 120 patients, and a further expansion is underway,” the group says in its latest statement.

“It is simply unacceptable that, five months after the declaration of this outbreak, serious discussions are only now starting about international leadership and coordination,” Brice de le Vingne, MSF Director of Operations, adds in a statement. “Self-protection is occupying the entire focus of states that have the expertise and resources to make a dramatic difference in the affected countries. They can do more, so why don’t they?”

“We need to be one step ahead of this outbreak, but right now we are five steps behind.”

One problem is that the three countries affected — Sierra Leone, Guinea and Liberia — had tottering health systems to start with.

“The outbreak is spreading rapidly in Monrovia, overwhelming the few medical facilities accepting Ebola patients. Much of the city’s medical system has shut down over fears of the virus among staff members and patients, leaving many people with no health care at all, generating an emergency within the emergency,” MSF continues.

WHO says more than 240 health care workers have been infected in Guinea, Liberia, Nigeria, and Sierra Leone, and more than 120 of them have died.

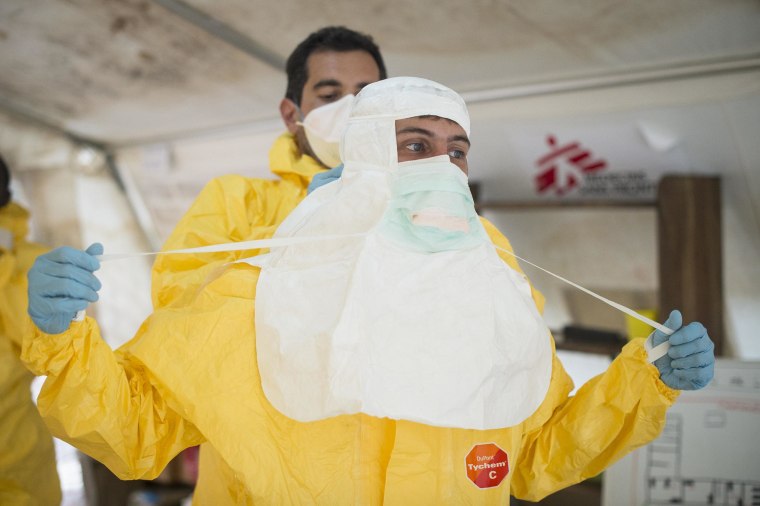

And it’s taking a toll on a personal level. Wolz described the cumbersome system health workers use to protect themselves — putting on layers of plastic garb from head to toe, a process that can take several minutes. It then must be taken off in careful reverse order to protect against contamination.

“No one should wear the PPE for longer than 40 minutes; it’s unbearable for any longer than that, but it’s easy to lose track of time, so we have to monitor our colleagues,” Wolz says.

And the situation makes it difficult to care for patients in the way that nurses do best, with plenty of touching and reassurance. “We have a psychologist, a counselor, and health promoters to help and support patients, but there are just too many of them. There’s also a tent for the most severely ill patients,” Wolz writes.

“I try to spend more time there than in the other tents, if only to hold patients’ hands, give them painkillers, and sit on the edge of their beds so that they know they’re not alone. But spending time is always difficult — there are so many patients waiting for help.”

WHO says it was forced to temporarily pull back some workers in Sierra Leone after one, a Senegalese epidemiologist, was infected and evacuated to a special hospital in Hamburg, Germany. And the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention pulled out a staffer who had a “low risk contact” with another infected worker.

“The CDC staff person is not sick with Ebola, does not show symptoms of the disease and, therefore, poses no Ebola-related risk to friends, family, co-workers, or the public,” the CDC said in a statement. “Ebola is not spread by persons who do not have symptoms of disease.”

Meantime, WHO confirms there is a separate and unrelated outbreak of Ebola virus in the Democratic Republic of Congo, with 24 suspected cases and 13 people dead so far.