The head of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency's water office told lawmakers Wednesday that Michigan authorities broke federal rules requiring them to add anti-corrosive materials to drinking water pumped into Flint homes, triggering a lead-poisoning crisis.

But critics also accused the EPA of covering up what it knew about that misconduct while Flint residents continued drinking the tainted water.

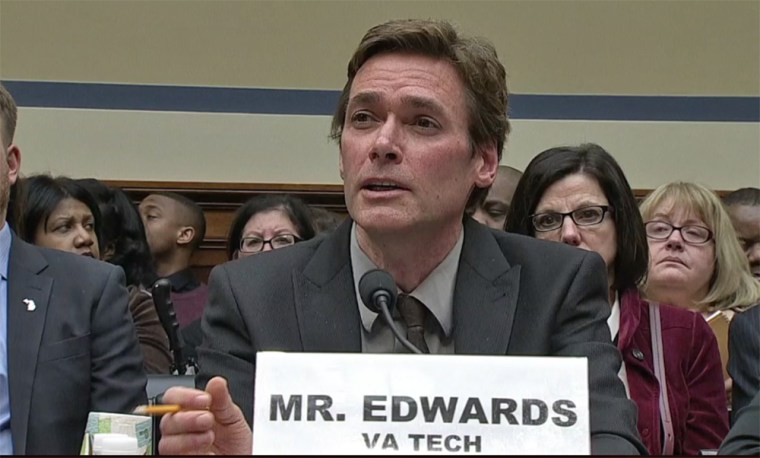

"If it's not criminal, I don't know what is," Marc Edwards, an engineering professor at Virginia Tech who helped uncover the pollution, told a House Oversight Committee hearing on the crisis.

Blame ricocheted around the room for hours, as lawmakers, a researcher, a Flint mother and government officials debated failures by Michigan's Department of Environmental Quality and the EPA to deal with lead from corroded pipes that began leaching into city homes following the city's 2014 cost-saving move to start pumping water from the Flint River.

The unfolding crisis, now under criminal investigation by state and federal authorities, caused elevated levels of lead in the blood of thousands of Flint children.

The EPA's water official, Joel Beauvais, said the Department of Environmental Quality first said corrosion treatment wasn't needed for the river water, then "resisted" demands to follow rules requiring it.

The state agency's new head, Keith Creagh, didn't fight that characterization. "We were minimalistic and legalistic in our behavior," he said.

But Beauvais, too, came under withering criticism from lawmakers who asked why the EPA didn't tell the public after one of its workers reported high concentrations of lead in a Flint home in February 2015.

"I don't know the answer to that question," Beauvais told chairman Jason Chaffetz.

"You can't come to a hearing without the answer to that question," Chaffetz shot back. "The crying shame here is, when they knew there was a problem, they should have told the public."

Lee Anne Walters, the mother who'd called the EPA to her house, recalled her lonely crusade for answers, ultimately finding Edwards. Tearing up, she said her son is suffering from anemia and learning issues as a result of lead poisoning.

"The city and MDEQ still told people the water was safe, while the EPA watched in silence," she said.

Michigan Gov. Rick Snyder said Wednesday he will propose $30 million in state funding to help pay the water bills of Flint residents facing an emergency over the city's lead-contaminated water supply.

Conspicuously missing from the hearing was the state-appointed official who ordered the city's fateful switch in water sources.

Lawyers for the official, Darnell Early, have said that he didn't get the subpoena from the committee in time to travel to Washington, and that he was too busy dealing with another crisis: deteriorating conditions in Detroit public schools.

Chaffetz vowed to ask U.S. Marshals to "hunt him down" to make him testify.

"This is a failing at every level," Chaffetz said.

The crisis dates to the city's unusual decision, under leadership of Early, to save money by switching from Detroit's water system to the Flint River. The river water ate away at old pipes, delivering lead-tainted water to customers. A chorus of residents and scientists raised warnings, but government officials insisted for months that the water was not dangerous.

“There was a continuous effort to try to minimize this problem as if it did not exist.” Flint Congressman Dan Kildee told the panel.

Since late last year, when the crisis boiled over, the city's people have been drinking bottled water, with help from donated home filter systems. The Flint River water still is not drinkable, officials said.

Edwards said he'd been warning the EPA for years of the weakness of federal laws meant to prevent such disasters from happening.

"All we learned is that the agencies paid to protect us from lead in drinking water can get away with anything," Edwards said.

He described the situation in Flint — the misguided switch, the sloppy testing, the slow government response — as "part '1984' and part 'Enemy of the State.'"

Edwards added, "And I am personally shamed that the profession I belong to, the drinking water industry in this country, has allowed this to occur.”

Melissa Mays, a mother of three, was among dozens of Flint residents who took an overnight bus to attend Wednesday's hearing.

“It’s nice to see we’re not the only people yelling at these people anymore,” she said. “Lawmakers, respected people, are saying this is wrong, this is criminal, this has got to stop.”

Mays, 37, said she hoped the next hearing would include the people accused in the cover-up, including Early, and workers from MDEQ and EPA.

“Until they’re there under oath, it’s just not enough,” she said.