First water, then red ink: The nightmare of Hurricane Harvey’s deluge of Houston could be exacerbated by the cost of recovery.

Experts say the unique nature of Harvey’s devastation means affected residents — and FEMA’s already-broke flood insurance plan — will be the ones reaching into their pockets to rebuild.

The early figures are fluid and likely to change, probably increasing as the extent of the damage becomes more clear. And early estimates of aggregate losses already vary widely, depending on whether the figure includes insured and uninsured property damage, or indirect impacts like lost worker productivity and economic output.

Texas Gov. Greg Abbott said Wednesday his state could need upwards of $125 billion from the federal government to help it recover.

A preliminary analysis by catastrophe-modeling firm RMS estimates that wind, storm surge, and flood damage could collectively total between $70 billion and $90 billion. Moody’s Analytics put the estimate this week at between $45 billion and $65 billion in damages to homes, businesses and public infrastructure, according to chief economist Mark Zandi. “I’m sure that’s going to go higher, but that’s our current estimate,” he said, adding that this figure does not include up to an additional $10 billion in lost economic output.

For residents of Houston and other waterlogged communities, the more pressing questions pertain to insurance: What’s covered, and who is responsible for those losses.

The state’s big insurers have been going into action. State Farm tweeted on Monday it was adding “hundreds of staff” to help customers file claims, and Allstate tweeted on Wednesday “We're moving into the areas affected by Harvey, ready to help start the recovery process."

Collectively, the two insurers have more than one-third of the homeowners insurance market share in Texas, according to Morgan Stanley.

Most Homeowners Aren't Covered

But this might not hurt these insurers as much as might be expected — and individuals could find themselves with far less coverage than they expected. While most comprehensive car insurance policies cover flood damage, as a rule, homeowners’ policies don’t cover water damage resulting from floods; if wind shears off a roof and rain pours in, that damage is typically covered, but overflowing rivers or reservoirs or storm surges are not.

And those waters are responsible for the lion’s share of Harvey’s devastation. “Harvey is primarily a flooding event,” said Robert Hartwig, clinical associate professor of finance at the University of South Carolina and consultant to the Insurance Information Institute.

A small percentage of flood policies for homeowners are through private-sector insurance providers, but most are written through the National Flood Insurance Program, which subsidizes premiums paid by homeowners and businesses.

“Longer run, the program’s rates need to more truly reflect the actual risk that’s being assumed,” Hartwig said. But raising premiums, as well as other tactics, like redrawing flood plain maps or implementing more restrictive zoning to limit the number of vulnerable properties, inevitably face pushback from real estate and construction interests, along with local officials who want to add, not subtract, taxpaying home and business owners in their districts.

Since only homes with federally backed mortgages in FEMA-designated Special Flood Hazard Areas are required to carry insurance, a lot of Houston homeowners in low-lying neighborhoods are likely to find themselves without any financial safety net at all.

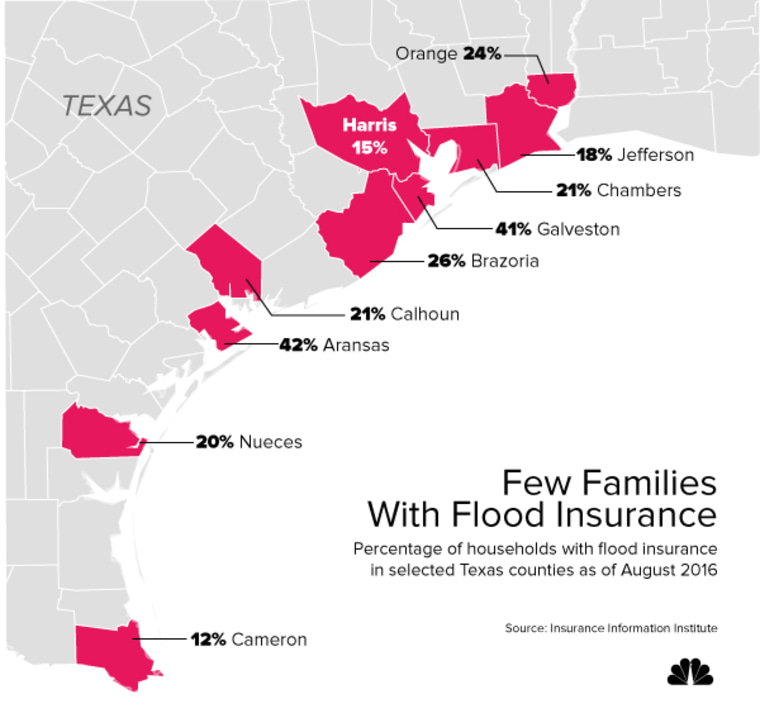

Real estate analytics company CoreLogic found that less than half of the homes and businesses at moderate-to-high flood risk in the Houston metro area are within an SFHA. Harvey’s waters spilled out over those boundaries many times over. Risk analysts estimate that only between 15 and 20 percent of homes in the Houston area were covered by flood insurance when Harvey inundated entire neighborhoods with water, which means much of the individual losses will be borne directly by homeowners.

New Storm Norm Has Led to $25 Billion Debt for Flood Program

Even as development has pushed further into low-lying areas, the nature of major storms has changed. “Many of the most severe events in recent years have tended to be very wet, with heavy rain and storm surge being the defining characteristics. This looks like the new norm,” Hartwig said. “It’s the principal reason why the NFIP is $25 billion in debt today.”

The beleaguered NFIP has two important deadlines coming up, and the impact of Harvey is likely to weigh on how lawmakers respond.

Its most recent five-year reauthorization is set to expire on Sept. 30. Congress can reauthorize it or extend the current reauthorization; although members of both parties have talked about the need to overhaul the money-losing program for years, political hurdles abound.

According to RMS, some half a million NFIP policies ultimately will be affected by Harvey. “Losses to the program will be very significant — potentially the largest event to date,” the company said. The program has a $30.4 billion borrowing limit from the U.S. Treasury; access to additional funds requires authorization by Congress.

Related: How Many Billions of Dollars Will Harvey Cost?

Steve Ellis, vice president at Taxpayer for Common Sense, said it’s likely that claims related to Harvey could easily top the difference between that figure and the program’s existing $24.6 billion debt, forcing an already dysfunctional Congress to confront a political quagmire.

“The borrowing limit issue is something that will be part of the discussion. It’s really hard to argue that everything is fine in the program,” Ellis said. Adding Harvey to a list of budget-busting storms that include Katrina and Sandy — an average of one every four years — makes it harder to call these weather events outliers, he added.

“The federal government cannot afford to pay subsidized insurance year after year and not incorporate those changes into their statistical databases,” said Jim Blackburn, co-director of the severe storm center at Rice University, who says lawmakers need to be persuaded to come to grips with changing weather patterns, for economic, if not environmental, reasons.

“We’re looking at a different reality as far as rainfall events in Houston,” Blackburn said. “This storm just blows any concept of the 100-year floodplain away… if FEMA doesn’t get a handle on a reasonable 100-year floodplain, then that whole program is absolutely doomed.”