Seven times, Tommy Arthur has escaped death. With his eighth execution date less than a week away, he phoned from an Alabama prison to talk about the increasingly slim chance that his lethal injection will be called off yet again.

"Until I take my last breath I’ll have hope," Arthur, who has been on death row for almost 35 years, told NBC News on Friday. "I don’t know how to quit. I don’t know how to give up."

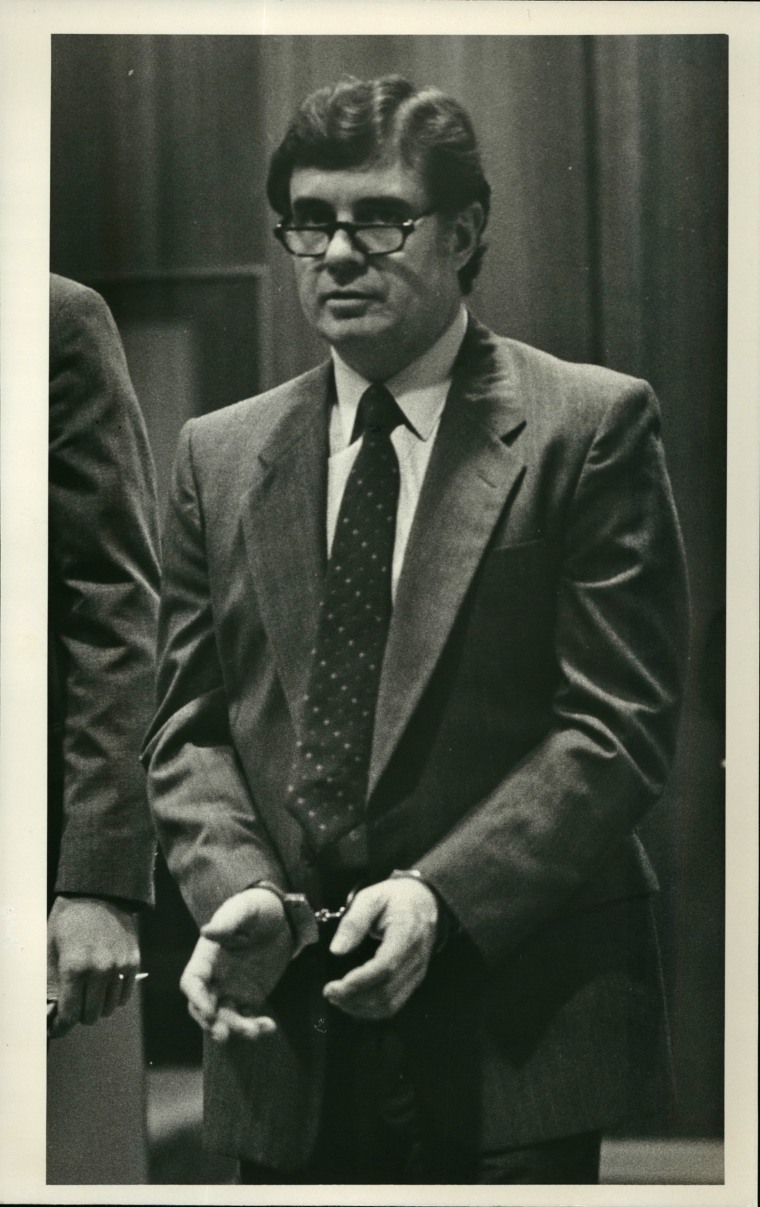

He has the paperwork to prove it. Sentenced to death for a 1982 contract killing he insists he didn't commit, Arthur has filed a mountain of challenges, many of them successful — at least in the short run.

The U.S. Supreme Court halted his last scheduled execution six months ago but later declined to take up his case. More recent appeals have been rejected, and while Arthur's attorneys are continuing to fight, the prospects for another reprieve are growing dimmer.

Related: Supreme Court Delays Inmate Tommy Arthur’s Seventh Execution Date

Alabama Gov. Kay Ivey last month shot down a request for new, enhanced DNA testing of a wig from the crime scene, which Arthur, 75, contends will prove that someone else is responsible for the murder of Troy Wicker. She's considering a request to test a hair he claims was collected.

"There is evidence in the evidence box that can be and should be DNA tested and they are not doing it," he said. "I asked them, 'Please don't let Alabama kill me without testing it.'

"Honest to goodness," said Arthur, who was found guilty by three different juries, "I did not commit this crime."

Related: Death Sentences Drop to 40-Year Low, Report Finds

Arthur's odyssey through the justice system began in 1977. That's when he was sentenced to life for fatally shooting his sister-in-law through the eye. He joined a work release program, and according to court records, began an affair with a married woman named Judy Wicker.

By prosecutors' account, Wicker offered Arthur $10,000 to kill her husband, Troy. Arthur dressed up as a black man, in an Afro wig, and shot the sleeping man through his eye, prosecutors say.

Arthur and Judy Wicker were convicted at separate trials. Although she initially claimed she had been raped by a burglar who shot her husband, she later changed her story and testified against Arthur at his retrials.

Arthur's first conviction was overturned because the court found details of the earlier killing were improperly disclosed during the trial. His second guilty verdict was tossed over a statement he gave to police without a lawyer present.

At Arthur's third trial in 1992, Arthur was convicted and sentenced to death again — after telling the jury he wanted a capital sentence because, he said, it would give him better tools to appeal the verdict.

The third conviction stuck — and the Alabama Supreme Court set execution dates in 2001, 2007, 2008, 2012, 2015 and 2016.

Each time, they were postponed, once after a fellow inmate claimed in writing that he was the real killer, only to clam up on the stand during a hearing where Judy Wicker again swore Arthur was the gunman.

Arthur is now the third longest-serving death-row inmate in Alabama, where the legislature just passed a measure that would hasten executions by speeding up appeals. He has several pending appeals that have to be resolved before his May 25 execution date.

One challenges Alabama's lethal injection protocol, which uses the controversial sedative midazolam, on the grounds that it will cause suffering. It cites the December execution of Ronald Smith, who witnesses said heaved and coughed for 13 minutes and moved his arm during a consciousness check.

"It's inevitable that I'm going to have some problems if they execute me," Arthur said.

Another appeal attacks the state's former sentencing scheme, which allowed judges to overrule juries and impose death sentences and which the governor just overturned.

Arthur, who has encyclopedic knowledge of his case, is most focused on another avenue: his quest to have the killer's wig subjected to a new type of DNA testing that could turn up genetic material that might have been missed by earlier tests.

On April 26, the governor's counsel turned down that petition, saying it "merely recycles the same request and contention made by Arthur for more testing on a piece of evidence that has been shown to contain no DNA profile."

Arthur said he doesn't understand the state's reluctance. "Why won't they let this testing take place? What would it hurt?" he asked.

His lead attorney, Suhana Han, said that "neither a fingerprint nor a weapon nor any other physical evidence" links Arthur to the crime.

"If the state executes Mr. Arthur on May 25 as planned, he will die without ever having had a meaningful opportunity to prove his innocence, an outcome that is inexcusable in a civilized society."

An advocacy group called Victims of Crime and Leniency said the courts have given Arthur enough second chances over the last three decades.

"He's Houdini," said Janette Grantham, the executive director. "He escapes and he escapes."

She said that for many years, she had been in contact with Troy Wicker's sister, who showed up for several executions that were then called off at the last minute.

"She died a couple of months ago so she won't make it to the final execution," Grantham said. "To me, that is very sad."

However the courts rule, Arthur said, he does not plan to apply for clemency; in his view, it would amount to an admission of guilt.

"I'm not interested," he said. "I could have pleaded guilty to this in 1982 and taken a straight life sentence but I'm not going to plead guilty to something I just didn't do."