There is a Ferguson, Missouri, that most Americans know: The town where a police shooting triggered violent protests, a federal civil rights investigation and a national debate on law enforcement's treatment of minorities.

But then there is the Ferguson that new arrivals see: cheap housing, a diverse population and vibrant community activism.

That second vision is helping to keep the city's struggling real estate market alive.

A year after Michael Brown's death tore Ferguson apart, homes are selling, but at a slower pace. Prices have dropped, but the $50,000 median price so far this year is on par with 2013, according to data provided by agents.

Among those moving in are young families and single strivers, fueling hope for the small city’s rebound.

Here are some of their stories.

Returning home

Luke Hayes grew up in the suburbs north of St. Louis, and for years dreamed of coming back.

The public school teacher and his wife scouted several towns in the area before settling on Ferguson. On July 31, they closed on a three-bedroom Colonial near police headquarters that cost them $110, 000.

The couple, who have a 2-year-old daughter named Finley, had lived in Indiana and Kentucky. Friends and relatives worried they were moving into a war zone.

But where the others saw liabilities, the Hayes family saw promise.

“It offers so much more than a quality of life," Luke Hayes, 32, said. "It offers different experiences and diversity Finley may not have had if we’d stayed living where we were.”

"We liked the community feel of it," Ashley Hayes, 34, added. "The character, the charm. There’s a lot of cute stuff around.”

The young family did have concerns. They weren't sure if their home's value would increase. They weren't sure if they wanted to send their daughter to the local public schools. But they say they were not turned off by Brown shooting, or its aftermath.

The city "is different, but I think what has changed is how people see it," Luke Hayes said. "But not how people in the community live and experience day-to-day life."

They're also not unsettled by the flashes of unrest late Sunday on the one-year anniversary of Brown's death.

“Obviously there’s still tension and things aren’t resolved, so it didn’t surprise me at all, or worry me, or make me second guess our move,” Ashley Hayes said. “To me it was expected something would be happening because it was the anniversary. Do I except this will go on all the time? No.”

And though Hayes admits hearing the sounds of sirens outside of her window was different than hearing about chaos on the news, she said that the family was more afraid of the thunder and heavy rain that hit Fergusonon Sunday night. "That was more scary — thinking about tornadoes that could come through here.”

They try to see Ferguson through their daughter's eyes.

“I’m sure the events of last August will color Finley’s perspective, but I hope that those aren’t the first things she thinks of," Luke Hayes said. "I hope she thinks, 'This is my home, my neighborhood,' and gets nostalgic when she drives down streets. Not, ‘I live in Ferguson where this awful thing happened.’”

Called to help

Jonathan Thomas, a Christian minister, was living in Indianapolis when he first visited Ferguson last September to support local churches dealing with the riots and their aftermath.

The effort was supposed to be temporary. But Thomas, 34, said he soon realized he needed to be there all the time, to be “an agent of healing" in a place he saw as a hub of the modern civil rights movement.

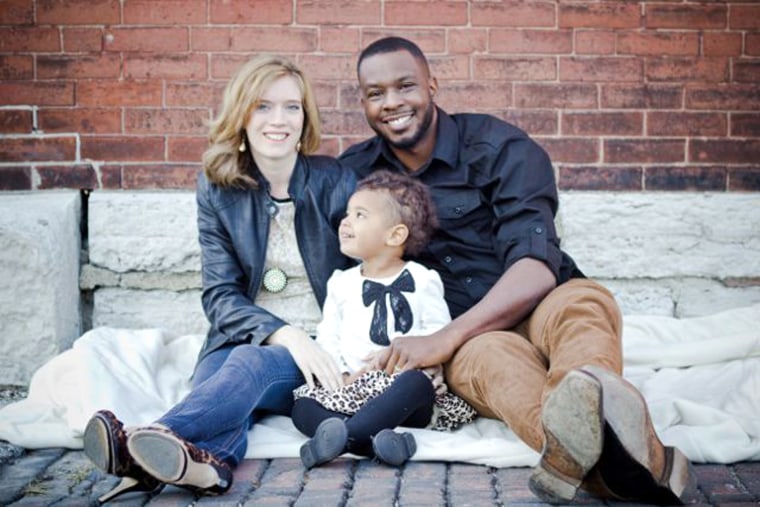

So Thomas brought his wife, Mollie, 35, and their 4-year-old daughter, Mira, with him. They moved into a friend's place in St. Louis and began looking for a home to buy in Ferguson.

He said they are looking for a place that is close enough to Ferguson's most vulnerable communities but safe enough for him to feel comfortable leaving his family behind when he travels.

Thomas said he sees Ferguson as being no different from many other towns in the St. Louis area.

“What I’ve found engaging with the people here is that Ferguson, though divided, is really a nice, small quaint little town that has been stigmatized and victimized" by institutionalized discrimination, he said.

He also believes his family can help move Ferguson forward: he is black, and his wife is white.

“There are wounded black folks in Ferguson and St. Louis who have never had deep relationships with white folks, and we get to model that,” Thomas said. “On the other hand, there are white folks afraid to come to Ferguson, especially now, because they have a certain idea in their mind of what it will look like with angry blacks who will attack them. So for my wife, it's an opportunity for her as a white person to defer that fear in people’s minds.”

Unrest on Sunday night only fueled Thomas’ belief that his family has a role in Ferguson.

“I think violence begins with people, so non-violent people have to move into places where there is violence in people’s hearts and change that.”

Thomas spent Sunday evening on West Florissant Avenue having conversations with locals and praying. He headed home three hours before reports of gunfire.

“I wasn’t scared because I’ve done work in gang involved communities for a long time, so I’ve been in environments with gunfire before,” Thomas said. “It’s definitely not the kind of environment I’d bring my family directly into, but in terms of that influencing whether or not we want to live in Ferguson, that doesn’t really influence it.”

Building a bridge

Courtney Curtis grew up in Ferguson, and still believes in his hometown.

He moved to neighboring Berkeley three years ago to help his grandmother, and during that time was elected to represent the area in the Missouri House of Representatives.

Two months after the Michael Brown shooting, Curtis, a 34-year-old bachelor, came back, renting an apartment in a complex called Arbor Village, just off South Florissant Road, near one of the city's commercial districts.

Since returning, he has become reacquainted with the divide between residents who are resistant to change and those who believe change is necessary for the city to move forward.

“We have the 'I love Ferguson' faction of the community, which sees Ferguson one way, whereas individuals like me, who grew up in the more impoverished area, see it a different way," Curtis said. "And there still hasn’t been a bridge to bring us together.”

Curtis hopes that he can help bring those sides together — even if the process seems painfully slow.

His dream is a Ferguson that attracts a mix of young and old, becomes a hub for small business startups and develops trust between police and the public.

“Ferguson can be a lot of things," Curtis said. "We still have a faction of the community that wants Ferguson to be the same, but Ferguson can be everything that’s the opposite of what the world thinks of Ferguson today."