The abrupt decision to shift the hunt for the missing Malaysian plane by 700 miles is the latest turn in an investigation defined by false hope.

From the first hours of the mystery, lead after lead has gone nowhere. It has left investigators under pressure, the clock ticking before the plane’s black boxes stop pinging, and the anguished families of 239 people hanging in the balance.

International politics has bedeviled the investigation. China and Vietnam have both called out Malaysian authorities for releasing confusing information, and U.S. officials said early in the probe that Malaysia wasn’t sharing all it knew.

“This investigation is an example of what not to do,” said James Hall, a former chairman of the National Transportation Safety Board who presided over the probe into the crash of TWA Flight 800 in 1996. “Everything they do, they change.”

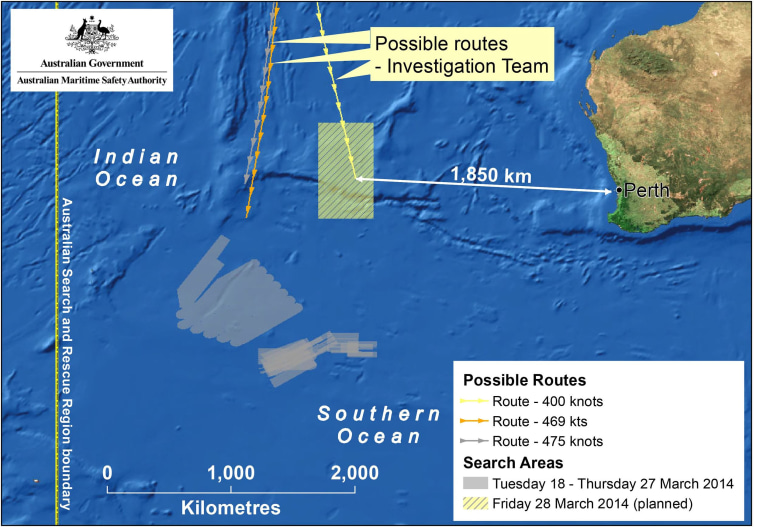

The geographic shift on Friday was based on advice from Malaysian investigators, who, relying on new analysis of radar data, determined that the plane was flying faster than first thought, burned more fuel and probably crashed earlier.

“We are starting all over again, with a blank page,” Charitha Pattiaratchi, an expert in oceanography at the University of Western Australia, told TODAY.

Early days

The first 24 hours of the search turned up what looked like promising developments: An oil slick was spotted in the water between Malaysia and Vietnam, and two men were found to have boarded Flight 370 with stolen passports.

But investigators quickly determined that the oil slick was not consistent with jet fuel, and Malaysian police said that the two men were probably seeking asylum.

Then, five days after the plane vanished, came the first of what has become a familiar sight: China released blurry satellite photos of large pieces of debris bobbing in the South China Sea.

The Chinese military called it a “suspected crash area.” It was yet another dead end.

Shifting paths and timelines

The first week of the hunt for Flight 370 was concentrated close to where the plane last made contact with air traffic control, less than an hour into its flight from Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, to Beijing. The Malaysian military later said it detected the plane banking off course and to the left, toward the Andaman Sea.

Then, a week into the hunt, the prime minister of Malaysia emerged for the first time since the jet disappeared. Speaking slowly and somberly, he declared that Flight 370 had been diverted because of “deliberate action by someone on the plane.”

In a bombshell, he said that the plane had automatically communicated for hours with a satellite after it dropped off radar and might have ended up thousands of miles away.

That put the plane along one of two arcs, one mostly in the Indian Ocean and one along a vast stretch of land from the mountains of Kazakhstan across China into Southeast Asia. The northern arc turned out to be another apparent false lead.

Malaysian investigators also changed their account of the sequence of events in the cockpit before the plane disappeared.

They first said that the aircraft made its last contact with air traffic control before the plane’s automatic signaling system, known as ACARS, stopped working or was switched off. The CEO of Malaysia Airlines switched the order the following day.

In the Indian Ocean

The prime minister made a second appearance on Monday to announce a twist: Inmarsat, the British satellite company, had analyzed its data and further, using complex math, had determined that Flight 370 took the southerly path.

“It is therefore with deep sadness and regret that I must inform you that, according to this new data, Flight MH370 ended in the southern Indian Ocean,” he said.

Flying from Perth, planes from Australia, the United States and other countries began making long, daily flights — when the weather allowed — to buzz the water 1,500 miles away and look for debris.

Almost every day came sightings that raised hopes again: A Chinese satellite spotted a 74-foot object. The Australians found two, one of them large and rectangular. France picked up 122. A Thai satellite located 300 floating objects, “probably manmade.”

But the images were days old, and none of it was ever confirmed as wreckage from Flight 370.

Friday morning brought the latest and perhaps most dramatic turn in the mystery: Australia announced that it was abandoning the existing search zone and moving it 700 miles to the northeast.

Malaysia's civil aviation chief, Azharuddin Abdul Rahman, told reporters that he was “not at liberty” to give specifics on the aircraft’s path.

Aviation experts said that it was not unusual to revise and deepen existing radar analysis during an investigation. Initial radar data from the 1999 plane crash that killed golfer Payne Stewart, for example, put the plane in Chicago and southern Canada before it was discovered in South Dakota, Hall said.

Still, the experts said they were surprised that it took so long for investigators to perform the advanced calculations for Flight 370. John Cox, the former top safety official for the Air Line Pilots Association and an NBC News analyst, questioned why it didn’t happen last week, when Inmarsat, the British satellite company, crunched its own data and eliminated the northern arc.

“The Malaysians have got to turn to outside sources and trust them and give them every bit of data,” Cox said. “This investigation is going to challenge the best investigative agencies in the world. But all of them need to be together.”

Search goes on

Ten aircraft took off from Perth on Friday to check out the new search zone. Five spotted objects, several described as light in color or blue-gray, the colors of the missing jet. But investigators, burned too often already, cautioned that nothing was for sure.

They defended the course of the search.

“This is the normal business of search-and-rescue operations — that new information comes to light. Refined analyses take you to a different place,” said John Young, an official at the Australian Maritime Safety Authority. “I don’t count the original work a waste of time.”

At the same news conference, Martin Dolan, chief commissioner of the Australian Transport Safety Bureau, reminded reporters: “This has a long way to go yet.”

The Associated Press and Reuters contributed to this report.