The biggest aviation puzzle of modern times, the disappearance of Malaysian Airlines Flight MH370, could take decades to solve, one of the airline’s own leaders said — and the key to unlock the very first door still hasn't been found.

Intrigue about the airliner's disappearance March 8, including any possible explanations, will continue to mystify until and unless an answer is found to this most basic question:

Where Is the Plane?

The best guess is somewhere in the southern Indian Ocean, according to officials of Malaysia, Australia and China, the three countries leading the search effort. They're tentatively planning to announce a new search area Wednesday, but that could be delayed, the Australian Transport Safety Bureau said Tuesday.

Sign up for breaking news alerts from NBC News

That's a big area: almost 3 million square miles, or about 1½ percent of the Earth's surface. Large parts of it have already been scoured by ships, planes and a sub.

The search began when the jet lost contact with air traffic control after it took off from Kuala Lumpur to Beijing on March 8. The first focus was off the coast of Vietnam, where oil slicks, debris and three mysterious floating objects all turned out to be unrelated.

Speculation then turned the other way: Perhaps MH370 for some reason reversed course and went down in the Andaman Sea or the Bay of Bengal. Nothing was found.

Nine days in, on March 17, the Australian government agreed to lead searches in a new location: in part of the Indian Ocean south of Sumatra, about 2,000 miles southwest of the Australian port city of Perth.

As had happened in the first few days of the search, crews were distracted by false leads: photo images of possible debris that sent ships from a half-dozen countries on a fruitless mission, Chinese satellite images of a possible debris field, French and Thai satellite images of hundreds of floating objects.

Three weeks in, on March 28, authorities overcame logistical roadblocks and reassessed their calculations based on better estimates of just where radar tracks and available fuel might have been able to take the plane. They moved the search northeast almost 700 miles closer to Perth.

And as they found nothing, they kept moving: east, then north, then deep underwater using the Bluefin-21, a U.S. Navy robotic submarine sent to follow a series of "pings" that authorities thought could have been picked up from the jet's black box data transmitters. That effort was declared a bust on May 28.

What About the Black Boxes?

In April, Bluefin-21 was deployed to a 300-square-mile area about 1,000 miles off the northwest coast of Australia after the mysterious pings were heard by a towed pinger locator. One last ping was picked up April 8, and authorities began searching a 12-mile-wide circle to no avail.

If the black boxes' transmitters survived the crash, they're probably useless now. They're projected to have a battery life of only about 30 days, a shelf life that would have expired 2½ months ago. And without guidance from the data transmitters, search crews are taking educated throws at a vast dartboard.

Even the world's biggest jetliners are microscopic in relation to the vast scope of the Indian Ocean, the deepest southern parts of which have never even been fully mapped.

Many experts believe the plane would have smashed into tiny bits if it crashed into the rough seas. That means search crews aren't looking for a needle in a haystack — they're looking for specks of dust on the points of needles in a haystack.

More than 3½ months after MH370 disappeared, not a single piece of confirmed debris has been found. All other questions remain largely rhetorical until evidence from the plane itself can be located, among them:

Why Did the Plane Disappear in the First Place?

There are lots of guesses, but that's all they are.

The best working theory right now is that the plane flew high and fast on autopilot, before running out of fuel and crashing fairly close to where the search is currently concentrated, several hundred miles off the Australian coast, commanders told NBC News.

But criminal investigators are chasing another theory. U.S. sources told NBC News that investigators have learned that the pilot, Zaharie Shah, 53, had used his personal flight simulator to practice journeys to remote parts of the Indian Ocean.

The Sunday Times of London reported over the weekend that Malaysian investigators are circulating reports to foreign governments identifying Shah as the "prime suspect" if the disappearance turns out to have been a deliberate act.

Files from Shah's flight simulator were deleted more than a month before Flight MH370 vanished, but The Sunday Times reported that the criminal inquiry was able to recover some of the missing files, which it said showed that Shah practiced taking a plane far into the Indian Ocean and landing on short island runways.

Shah has been described as a strong supporter of Anwar Ibrahim, Malaysia's leading opposition figure, who was jailed about eight hours before the jet — and Shah — disappeared.

Hishammuddin Hussein, Malaysia's defense minister and acting transport minister, said such reports were "not fair to the pilot's family," but investigators told reporters that they continued to pursue "every angle."

Still, authorities have dismissed other theories, such as one that posits the CIA took over the jet by radio for some unexplained reason or that the passengers hijacked it or that it was shot down by a foreign government because of some unknown material it was carrying. They said such suggestions were too speculative to waste time on.

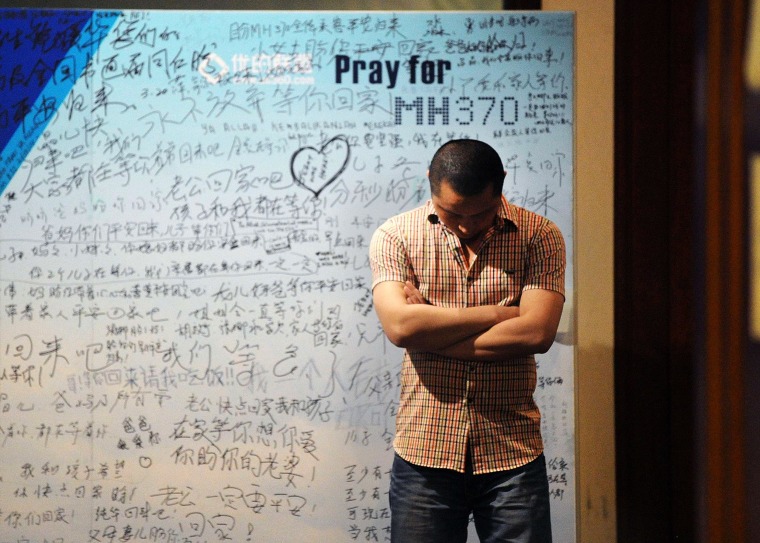

What About the Families?

Eventual compensation for the families of the 239 people aboard Flight MH370 also remains an open question.

Some of the families, which have loudly criticized Malaysian, Chinese and airline officials' handling of the investigation, began receiving payments of $50,000 apiece from a Malaysian Airlines insurance fund earlier this month. But beyond that, they're largely in limbo.

Datuk Abdul Aziz Kaprawi, Malaysia's deputy transport minister, told the upper house of Parliament on Monday that while the government is committed to compensating all of the families, "there will only be a final account when a final decision is made and the aircraft has been found."

Which takes us back to where we started.

"I think it could take a really long time to find," Hugh Dunleavy, Malaysia Airlines' commercial director, told the London Evening Standard newspaper. "We're talking decades."