The following report is from PolitiFact, which has partnered with NBC News to fact-check candidates during the 2016 political season.

After the mass shooting in Orlando by a man who pledged allegiance to the Islamic terrorist group ISIS, Republican presidential nominee Donald Trump reiterated his call for a temporary ban on Muslims coming to the United States.

During an interview with Fox News’ Sean Hannity, Trump elaborated on one of the problems he sees with the Muslim community in America.

Hannity said that Muslims have different religious and cultural practices than many Americans. He asked Trump, “If you grow up (as a Muslim overseas) and you want to come to America, how do we vet somebody's heart and ascertain if they're coming here for freedom or if they want to proselytize, indoctrinate and bring their theocracy with them?”

Trump responded, “Assimilation has been very hard. It's almost — I won't say nonexistent, but it gets to be pretty close. And I'm talking about second and third generation. They come — they don't — for some reason, there's no real assimilation.”

Related: Clinton's Claim on Small Donors Is 'Mostly False,' PolitiFact Finds

We were intrigued by the question of whether “there's no real assimilation” among “second and third generation” Muslims in the United States. So we looked at the social-science data and sought expert opinion. (Trump’s campaign did not respond to an inquiry for this article.)

We concluded that the implication of what Trump said — that Muslims want to isolate themselves from the mainstream American culture — is flat wrong. However, we also learned that the question involves some important nuance. In particular, the task of “assimilation” facing post-1960s immigrants to America is more complicated than, and thus distinct from, what it was for white, Christian, European immigrants who came to the United States in prior generations.

By and large, Muslims want to embrace an American identity

Several academic studies in the past decade have demonstrated that Muslims do indeed want to become integrated with mainstream American life.

One of the major surveys is from 2011, when the Pew Research Center conducted telephone interviews with 1,033 Muslims in the United States, in English, Arabic, Farsi and Urdu.

The researchers concluded that “Muslim Americans appear to be highly assimilated into American society.”

Specifically, 56 percent of Muslim Americans said that most Muslims coming to the United States today want to adopt American customs and ways of life. Only 20 percent said most Muslims coming to the U.S. want to be distinct from the larger American society, Pew found, while 16 percent said Muslim immigrants want to do both. (Incidentally, this is far different than the views of Americans at large; just 33 percent of Americans of all backgrounds told Pew that most Muslim immigrants want to adopt American ways, while 51 percent said Muslim immigrants want to remain distinct from the larger culture.)

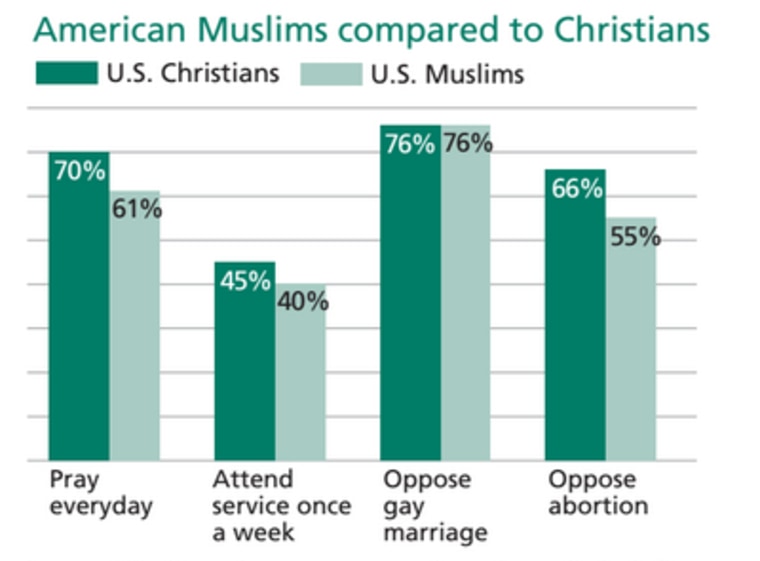

Notably, Pew found some striking similarities between the views of American Christians and American Muslims.

For instance, about half of Muslims said they thought of themselves first as Muslim, rather than as American. A different Pew survey found a nearly identical fraction of Christians in the United States, 46 percent, saying they thought of themselves first as Christian, rather than as American. And near-identical percentages of Muslims and Christians said there was no conflict with being devout in their own religion and part of a modern society. (Sentiments about identity were similar among native-born and foreign-born Muslims, though those born after 1990 had a somewhat larger preference for a Muslim identity.)

Jen’nan Ghazal Read, an associate professor of sociology and global health at Duke University, pointed to data from Pew and other sources showing similar rates of religious practice and beliefs among Muslims and Christians in the United States:

Other evidence lines up with what Pew found.

Selcuk R. Sirin, an associate professor of applied psychology at New York University's Steinhardt School of Culture, Education, and Human Development, found that even though 84 percent of 12-to-18-year-old Muslim Americans he studied had faced at least one act of discrimination in the previous year, most were comfortable with their "hyphenated identities" as both Muslims and Americans. "They seem to be pretty happy sitting on the hyphen," has said. "They don't feel the need to pick one over the other."

Akbar S. Ahmed, a professor of Islamic studies at American University, found similar sentiments when he did fieldwork for the book "Journey into America," which spanned 75 cities and 100 mosques.

“Muslims again and again told us that America is the best place in the world to be a Muslim,” Ahmed said. “There are countless examples of Muslims who are assimilated and are completely American in every sense.” He said that out of the roughly 2,000 personal interviews that comprised in his fieldwork, virtually all Muslims said that Muslims could be American.

“So it is dangerous, irresponsible and incorrect for Trump to make statements like this and demonize the entire community,” Ahmed said.

Some experts have said that, if anything, that the trend is moving even more strongly towards becoming American.

“In the 1970s and 1980s, Muslim leaders explicitly urged their people to avoid assimilating into the American mainstream and to withdraw into Islamic community centers, schools, and colleges,” Boston College political science Peter Skerry wrote in 2013. “Since 9/11, Muslim leaders have shown a remarkable — and largely unnoted, or disbelieved — willingness to adapt to America. Indeed, these leaders have been busily reconstructing an anodyne version of Islam that conforms to the American civil religion.”

In other words, Skerry wrote, Muslim Americans today “are being reassured that it is permissible—even desirable—to have non-Muslim friends. And that it is okay to attend business lunches where non-Muslim colleagues drink alcohol. And that it is definitely a good idea to vote and get involved in civic and political affairs.”

Integration is a bigger challenge for Muslims

So there’s clear evidence that, contrary to what Trump suggests, Muslims are embracing American identity and values.

At the same time, Muslim Americans by and large do not want to eradicate all traces of their religious and cultural heritage. This is similar to patterns seen in many immigrant groups that came to the United States beginning in the 1960s, when the nation’s immigration system was oriented away from its previous focus on European immigrants and toward other parts of the world.

Prior to the 1960s, most immigrants to the United States were white and Christian. They may have had national identities and cultural practices from their native country, but in most cases, they shared a religion and a race with the majority American culture. That meant it was easier for them to “assimilate,” as Trump said, in the larger culture.

But more recent waves of immigrants from Asia, India and the Middle East often have not shared the same race or religion as the American majority. So “assimilation” in the traditional sense has been a more complicated process. Assimilating to the mainstream American culture to the same degree as someone like Trump’s ancestors did (his grandfather emigrated from Germany) would require Muslims to renounce their religion and become Christian. (And, obviously, they could not change their skin color or other physical features.)

This has led scholars to shift away from the term “assimilation” and toward the term “integration.”

Sarah Lyons-Padilla, a research scientist at Stanford University, and Michele Gelfand, a professor at the University of Maryland, describe “assimilation” as part of an older “melting pot” model, while “integration” is more like a “mosaic.”

“We should not confuse integration with assimilation,” Lyons-Padilla and Gelfand have written. “Integration means encouraging immigrants to call themselves American, German or French and to take pride in their own cultural and religious heritage.”

Research by Lyons-Padilla and Gelfand found that Muslim-Americans’ support for “assimilation” — essentially, the melting-pot model — is low, statistically, at 1.76 on a 6-point scale. But they found support for the integration model to be quite high, at 4.96 out of 6.

“This tells you that Muslim Americans don't want to assimilate into American culture at the expense of giving up their own cultural identity, but they are very interested in embracing both,” Lyons-Padilla told PolitiFact.

She added that psychologists generally see the integration model as a more practical one to aspire to. “Decades' worth of research shows that people fare best when they can have a foot in both worlds,” Lyons-Padilla said.

Our ruling

Trump said that even among “second and third generation” Muslims in the United States, “there's no real assimilation.”

The data and the experts agree that Trump is wrong. Substantial evidence confirms that Muslim Americans want to have an American identity and think that doing so is achievable. In fact, their preferences for self-identification mirror those of Christian Americans.

The data shows that American Muslims want to be both American and Muslim. That’s different than the widely recognized “melting pot” model where immigrants of generations past blended in fully in their new country based on a shared religion and culture. But the reality is that for most Muslim Americans, religion and race would have made it impossible for them to follow that course in the first place.