"Selma" ignited controversy over whether its portrayal of the 1965 voting rights campaign misrepresents history. With the 50th anniversary of the landmark civil rights era struggle just weeks away, a closer look at the Hollywood film portrayal of this transformative moment reveals what media representations then and now got right, what they got wrong — and why it matters.

As a whole, Selma acknowledges the importance of “Bloody Sunday” as a television event, but the film doesn’t quite get things right.

The most famous moment from the Selma campaign was a television phenomenon: news coverage of the beating and gassing of nonviolent marchers on the Edmund Pettus Bridge who’d planned a march to the Alabama capitol in Montgomery to protest the disenfranchisement of black voters.

DuVernay’s film puts viewers right in the center of the violence as marchers choke on the gas, their bodies bludgeoned by state troopers’ clubs. The film asks viewers to be with the marchers, sharing and participating in their brutalization.

The TV newsfilm, on the other hand, situates viewers as onlookers.

We see people huddling around their televisions watching the coverage that seems to come to them live. Of course, in 1965 instant live feeds from remote news sites wasn’t possible. There were no satellite trucks. Newsfilm was film and had to be developed and flown to New York before it could be broadcast to the nation.

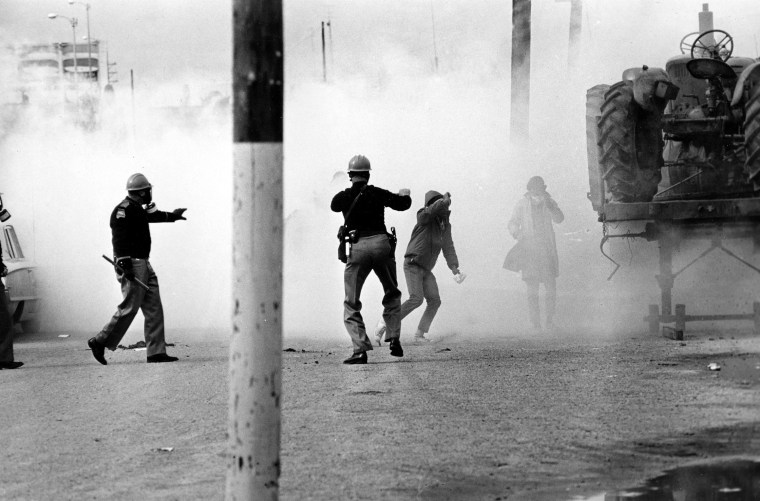

News cameras are cordoned off to the side of the road as they record a showdown between opposing forces: good versus evil, troopers plowing over a line of marchers. Once tear gas explodes, viewers can’t really see very much. The footage becomes like a horror film: what’s going on behind the plumes of smoke? We hear coughing, screaming, beating, but the monstrousness is obscured. Viewers may be encouraged to pity and sympathize with the victims, but unlike the vantage DuVernay provides, you aren’t urged to see yourself as one with them.

The actual story of how the Bloody Sunday coverage reached the public is more interesting and helps explain why that footage galvanized citizens, legislators, and commentators.

On Sunday March 7, ABC’s news division made the consequential decision to break in to the network’s prime time programming to show the Pettus Bridge horror. Just like today, Sunday night was the biggest night for TV watching. And ABC had a very special draw for viewers: a broadcast of the high profile motion picture with a star-studded cast of Hollywood luminaries, "Judgment at Nuremberg." The film dealt with the Holocaust and the moral culpability of Germans in the genocide of Jews. Approximately 48 million people tuned in. Even in those days of only three networks, news programming did not garner those kinds of viewer numbers.

Shortly after the film started, ABC interrupted the film with its report from Selma. The juxtaposing of a narrative about Nazi brutality towards victimized Jews with footage of Southern segregationist brutality against victimized blacks was incredibly powerful. Numerous commentators made the inevitable comparisons in the following days, making already powerful footage resonate even more forcefully.

One of Selma's attributes is its highlighting of various leaders and individuals associated with the Selma campaign, especially women: Amelia Boynton, Diane Nash, Annie Lee Cooper. While the film focuses on King, it doesn’t do so to the exclusion of these and other key figures. Annie Lee Cooper, a foot soldier in the Selma struggle and largely unknown before DuVernay’s film, is now almost a household name mostly because Oprah Winfrey portrays her. In her depiction, Cooper calmly and with tired dignity attempts to register, answering increasingly difficult legalistic questions only to be summarily denied in one of the film’s opening scenes.

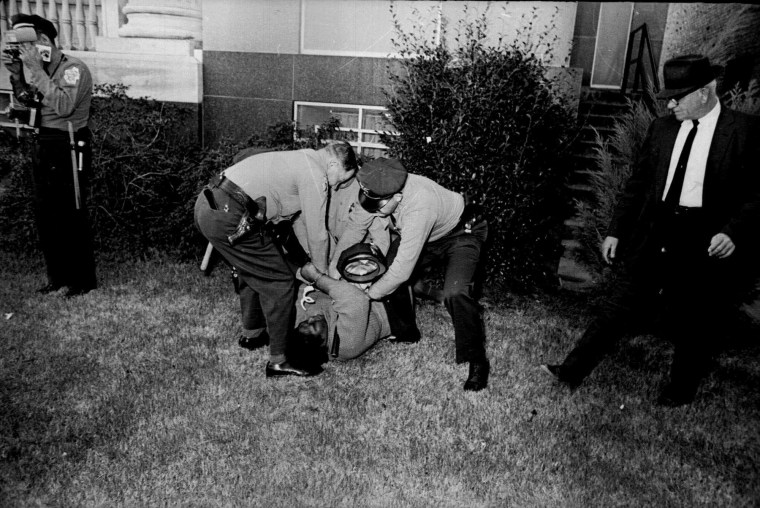

Cooper notoriously walloped the racist Dallas County sheriff Jim Clark who used all the means at his disposal to harass and abuse black citizens attempting to register. A photo of her confrontation with Clark splashed over the front pages of newspapers. While the New York Times’ caption noted that Cooper had hit the sheriff, the image conveys a message of white violence and police brutality.

DuVernay’s film shows Cooper retaliating against Clark because he has been brutalizing the Jimmie Lee Jackson family, including Jackson’s elderly grandfather. This motivation isn’t actually true. Jackson and his family were not part of the Selma movement, but rather the movement in nearby Marion. Nevertheless, the film shows us a protective, matriarchal Cooper coming to the defense of her people.

In 1965 CBS news provided its viewers a very different image of Ms. Cooper. (Note: CBS preserved and archived its aired coverage of the Selma campaign; unfortunately NBC appears only to have saved raw footage, not the finished news stories that aired on the network’s Huntley-Brinkley Report, its rival to the Cronkite broadcast.)

A story broadcast on Cronkite’s Evening News shows Cooper as disruptive and suspicious even before her confrontation with Clark. CBS cameras zoom in on her standing shoeless on the courthouse steps in a line of would-be registrants, her footwear beside her. In close-up she appears shifty-eyed.

In the struggle with Clark and his men, CBS shows her being rolled over and hauled up to her shoeless feet very inelegantly. Everything about the CBS portrayal of Ms. Cooper suggests that she is deviant, out-of-control, and responsible for the manhandling she receives. Clark is interviewed, out of breath, explaining how he and his men were attempting to create order. Ms. Cooper is never given the opportunity to speak.

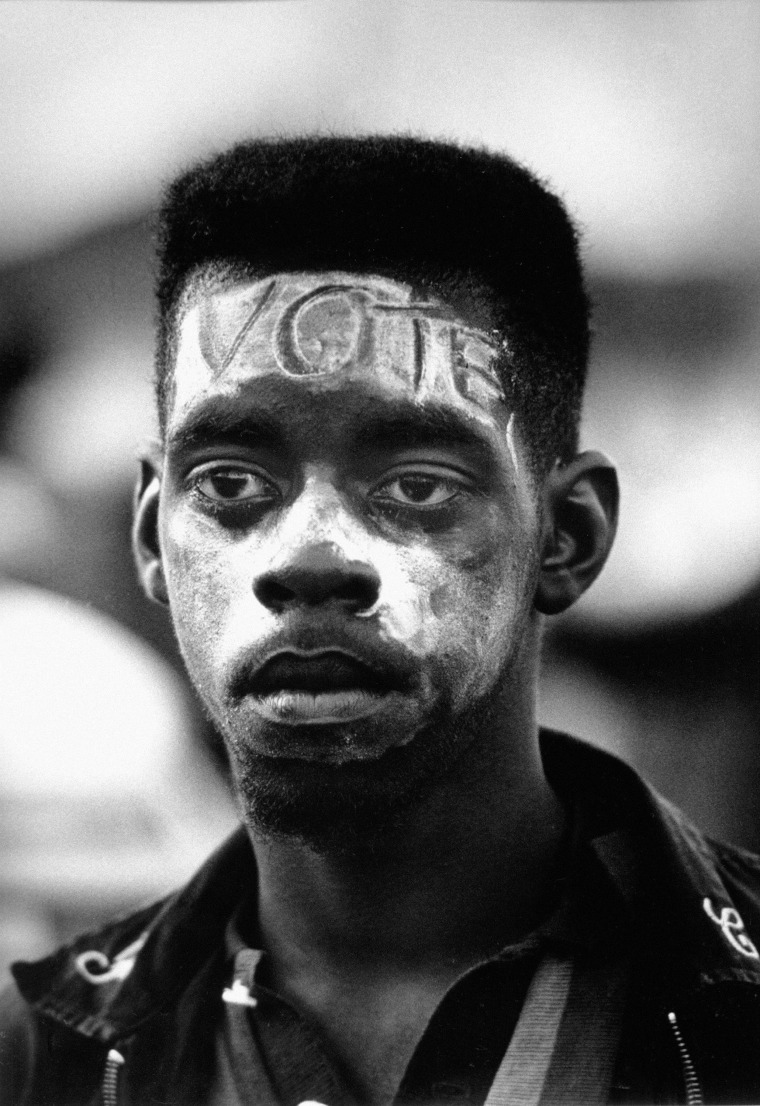

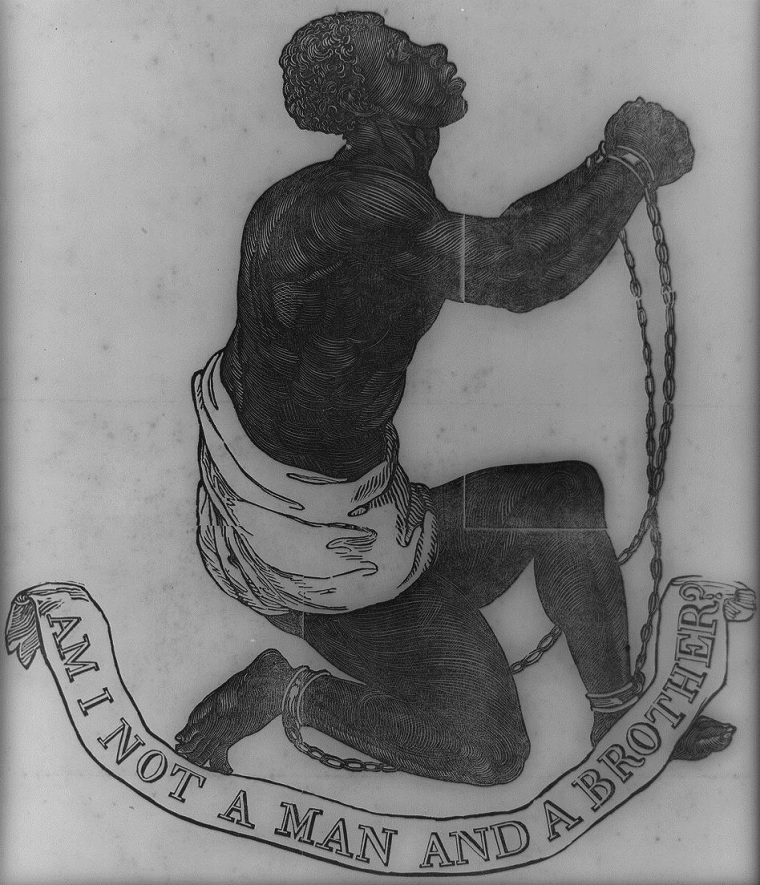

Annie Lee Cooper’s clobbering of Sheriff Clark obviously defied the Martin Luther King-led nonviolent strategies of the movement. But perhaps more importantly she defied a media script: civil rights activists were supposed to be objects of pity, abject and powerless, requiring help. (The iconic images of the 1963 Birmingham campaign illustrate this notion.)

It’s a script that did not begin with the civil rights era but can be traced back to the abolitionist movement and its “Am I Not a Man and a Brother Image” of a supplicating slave.

Life magazine’s photojournalism on Selma provides just the kind of imagery that fit the script. In an eight-page spread of dramatic photos, under the headline “Selma: Beatings Start the Savage Season,” we see the immediate aftermath of the “Bloody Sunday” mayhem with gas masked troopers and white onlookers standing and milling around while a lone black woman sprawls, prostrate on the ground, arms out. The photo caption helpfully explains the situation: “Dazed and wounded, Negroes helplessly await aid.”

Life magazine displays another recurring attribute of media coverage of Selma in 1965: an emphasis on the importance of white people. Two color photos dominate a full page and feature Mrs. Paul Douglas, the wife of an Illinois senator, who has come to Selma to lend her support. One photo shows her patting Martin Luther King’s shoulder approvingly. Was Mrs. Douglas in any way important to the Selma campaign? No, but she was white. Another large color photo shows kneeling clergymen and others under the looming figure of a club-wielding Alabama trooper. Their importance? They are all white.

The media in 1965 took a similar approach in covering Selma’s three martyrs: Jimmie Lee Jackson, the Reverend James Reeb, and Viola Liuzzo. Jackson and his family received next to no coverage. On the other hand, Reeb, a white Unitarian minister from Boston and Liuzzo, a wife and mother of five from Detroit were white. Their deaths received a great deal of coverage and interviews with family members.

"Selma" flips this script completely. Jackson, his mother, and his 82-year-old grandfather, Cager Lee, are significant side characters and the film provides a tender and poignant scene with King attempting to comfort the grieving Cager Lee. Reeb and Liuzzo are briefly introduced but are not in any way given privileged positions.

Ava DuVernay has said that she wasn’t interested in doing a “white savior” film, giving white audiences the white heroes they presumably need to identify with.

"Mississippi Burning" (1998) provided the Hollywood template for this way of telling the civil rights story. Two white FBI agents come to the rescue of brutalized black victims of segregationist racism in the Magnolia State following the 1964 murder of civil rights workers based on James Chaney, Andrew Goodman, and Michael Schwerner.

In "Ghosts of Mississippi" (1996), a heroic white district attorney finally brings the assassin of Medgar Evers to trial and conviction. "The Help" (2011) gave us another white savior in the civil rights years, also in Mississippi, providing the means by which black domestics can give voice to their oppressive conditions.

Selma, following on the success of Lee Daniels’ "The Butler" in 2013, is doing something very different: blacks are not only the subjects of their own stories, but the protagonists. This brings us to the LBJ controversy. Does film misrepresent the history? I won’t rehearse the arguments that have received plenty of media coverage already.

Some of the consternation may have to do with the fact the film does not give us a white hero, in this case a white president coming to the rescue of black victims. So used to having white good guys at the center of civil rights stories, Selma’s refusal to follow that script may be jarring to some.

There’s one characteristic that the film and the 1965 coverage do have in common: the privileging of King. In 1965 King was the only spokesperson that TV newsmen put on air. In the case of CBS news, it was King or nobody. Selma news coverage portrayed what appears to be a unified movement thoroughly under his command.

DuVernay’s film complicates this picture, showing the conflict between SNCC and SCLC and that there were leaders besides King. But, in the end, in DuVernay’s film, King still remains the crucial figure. Look at the film poster and the message it delivers: we are all situated behind King who dominates picture.

Ultimately why does it matter how the media, then and now, got Selma right or wrong? In 1965, the media’s focus on abject black victimization and on white participation may have helped to galvanize the country (at least outside the Deep South) in supporting voting rights. But it did so perhaps at the cost of seeing black people as fully human and in control of their own political movement and destiny. CBS’s portrayal of Annie Lee Cooper suggests what happens when black activists don’t conform to expectations.

Fifty years later, "Selma" asks audiences to embrace blacks as active agents, not victims to be rescued by privileged whites. The film implicitly challenges the sentiment encapsulated in Hillary Clinton’s much discussed declaration in 2008 that “Dr. King’s dream began to be realized when President Johnson passed the Civil Rights Act. It took a president to get it done.”

LBJ was certainly important to the passage of the legislation, but Clinton’s quote suggests King was merely a dreamer and that there were no activists organizing and pushing and demanding and forcing change. Selma provides a powerful corrective to fifty years of media representations that, while well-meaning, have given Americans a rather limited understanding of who made the civil rights movement a revolution.

As Common puts it in “Glory,” the film’s stirring theme song: “Glory is destined/Everyday women and men become legends.”