In the wake of the terrorist attacks on French satirical newspaper Charlie Hebdo, "Je Suis Charlie" has become a rallying cry in support of free speech.

It's printed along the bottom of Apple's French-language website. On Twitter, 3.4 million tweets in 24 hours included the hashtag #JeSuisCharlie. It has also become popular on Facebook, where #JeSuisCharlie ended a message from the service's founder and CEO, Mark Zuckerberg.

His post has garnered more than 300,000 "Likes." But not everybody agrees that Facebook never lets "one country or group of people dictate what people can share across the world," as Zuckerberg put it. That includes some people who commented under Zuckerberg's post, many of whom listed their location as in Pakistan or the Middle East.

"I'm not being 'another extremist' from Pakistan, but there should be proper guidelines as to what is appropriate and what's not," wrote a Facebook user based in Lahore.

It also includes Jillian York, director for international freedom of expression at the Electronic Frontier Foundation.

"When Mark Zuckerberg says that, he doesn't mean it," York told NBC News from Berlin. "I don't think Facebook stands for free speech at all."

She pointed specifically to Pakistan.

As a result of government requests, Facebook removed 1,773 pieces of content in Pakistan in the first half of 2014, according to the company's most recent transparency report. That trails only India and Turkey, where 4,960 and 1,893 pieces of content were removed, respectively, in the same time period.

Facebook declined to comment for this story.

On government requests, Facebook has said it only complies with them after a "thorough legal analysis."

But many requests don't involve governments — instead, content is removed when users flag it with the "Report post" button. What actually gets removed can be confusing.

In 2013, Facebook vacillated between banning videos of graphic beheadings and allowing them as free speech. Everyone from ISIS to Mexican drug cartels now use social media to get their message out to the world.

Facebook does not allow anyone with a "record of terrorist or violent criminal activity" to maintain a profile, but it can be hard to determine whether someone is part of a terrorist organization. Hate speech, threats of violence and bullying are all banned, but some of those areas become gray when users talk about politics.

York and some of the users who commented on Zuckerberg's post accuse Facebook's moderator of being quicker to ban politically charged posts from Pakistan and Palestine than those from the U.S. and Europe.

Of course, monitoring posts for all of these factors is a Herculean task. The fact that Facebook is approaching it with a sense of idealism is encouraging to Neil Richards, a law professor at Washington University in St. Louis.

"I think what Zuckerberg is trying to say is that Facebook is committed to Western notions of freedom of speech," Richards told NBC News. "I think that is true and laudable."

Facebook the giant

Many websites take down content people find offensive. Few have the global reach of Facebook, which has 1.35 billion monthly active users.

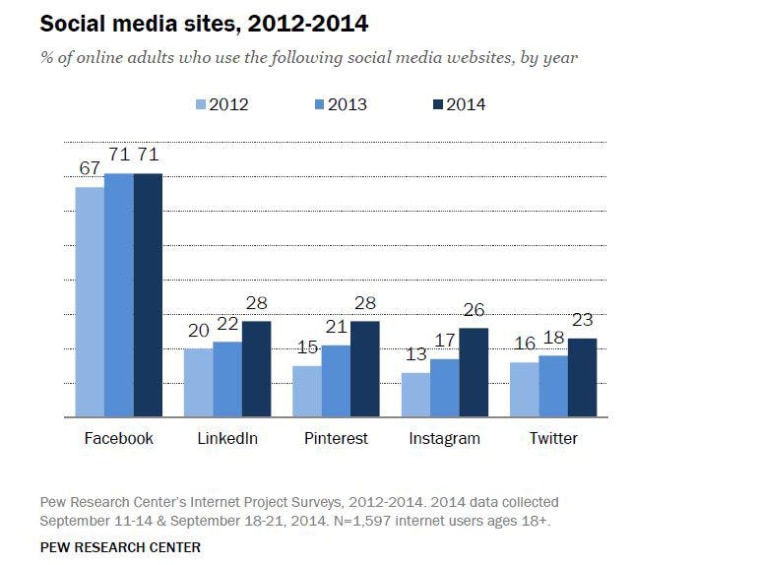

In the United States, 71 percent of adults who are online have a Facebook account, according to a Pew Research Center report released on Friday.

Navigating the choppy waters of "free speech" is tough enough for a newspaper or a Supreme Court justice. For a social network of more than a billion people, it can seem nearly impossible, which might explain Facebook's occasionally ad-hoc approach to taking down content.

"Implementing a pro-speech policy internationally has its own challenges because — even in the West — there is not a unified legal approach to protecting free speech," Morgan Weiland, a graduate fellow at the Center for Internet and Society at Stanford Law School, told NBC News.

If Zuckerberg is committed to free speech, York would like to see Facebook engage in more back and forth with local communities. That includes hiring more moderators who can speak Urdu and Turkish.

"I think the English-language moderation is much more consistent than the moderation in other languages," she said.

As for videos that show events like beheadings, warnings that require users to click through to watch should be used instead of taking the videos down, she said.

Regardless, Facebook can't just view itself as another social network. Companies like Google, Facebook and Apple are reaching near-monopoly status across the globe, Richards said, and that means that they need to play by a different set of rules than those that apply to small Internet startups.

"When these platforms become so big, they have to act like they are bound by something bigger than narrow corporate self-interest," Richards said. "They should allow raw, unfettered expression, including expression that people find offensive."