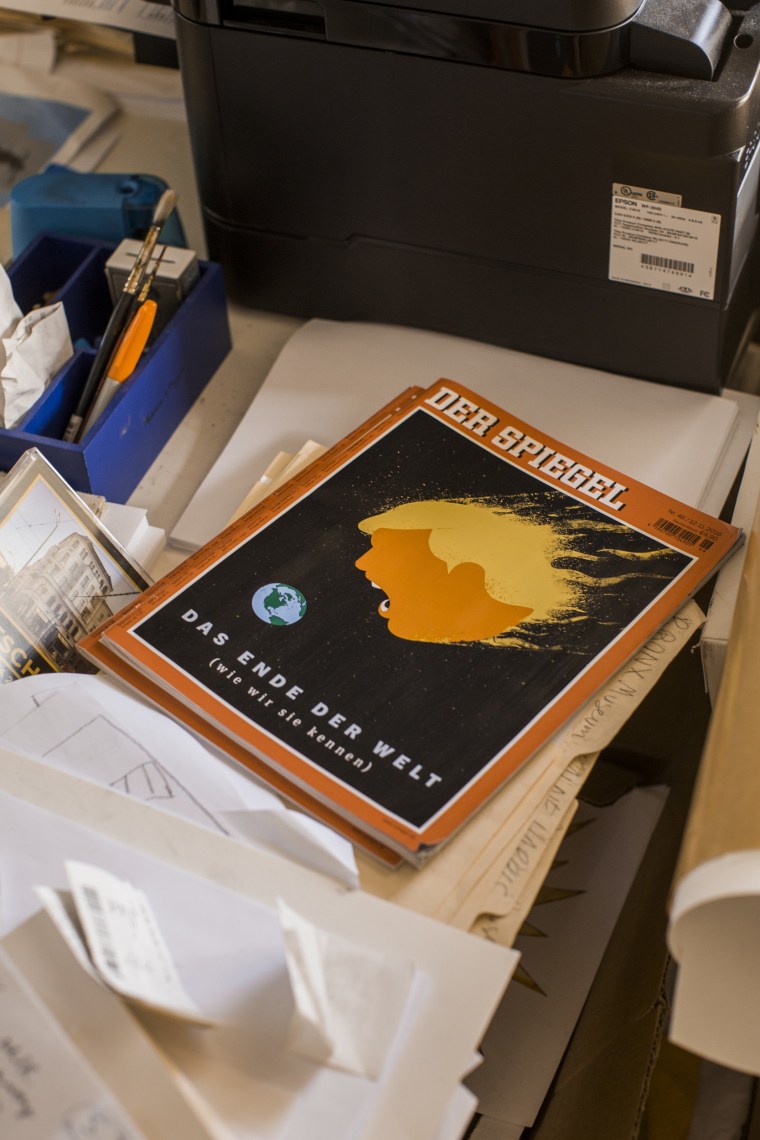

Cuban-American artist Edel Rodriguez has done it again. Last Friday the German publication Der Spiegel released the artist’s latest visual commentary on the state of American politics under the leadership of President Donald Trump.

As Trump meets the 100-day marker of his time in office, Rodriguez got in just one more illustrated jab, showing the heads of Trump and North Korea’s Kim Jung Un—mouths agape as if wailing—on babies’ bodies, wearing diapers, and straddling a missile on a bouncy spring. The image, a reference to the intense build-up of brink-of-war gesturing and its near immediate dissipation, is the first big follow-up to the cover that could be considered the artist’s proverbial mic drop.

As the news media and the nation reflect on the unfolding of the last 100 days, it seems pertinent to think back on how the artist’s work helped to shape the series of events.

In early February, Rodriguez rode the rolling wave of a media fever pitch when the cover of Der Spiegel featured his illustration of an eyeless President Trump holding the freshly decapitated head of the Statue of Liberty alongside the headline “America First.”

Much has been said of the image by now and the collaboration resulted in a radical artwork that endures long after the chatter has quieted. Still, the stir shocked Rodriguez—an artist with decades of work under his belt and an impressive portfolio of international exhibitions—who says people who know him were not at all surprised by the candor of his design. Now, he jokes after having to turn down interviews for lack of time, “Oh, so I’ve become that guy?”

Sensationalism aside, his covers have posed some questions about the work of political art, especially when the artist does not normally produce explicitly political works, namely: How does this imagery come about? And what role does it play once it’s here? For this artist in particular, that understanding begins in Cuba.

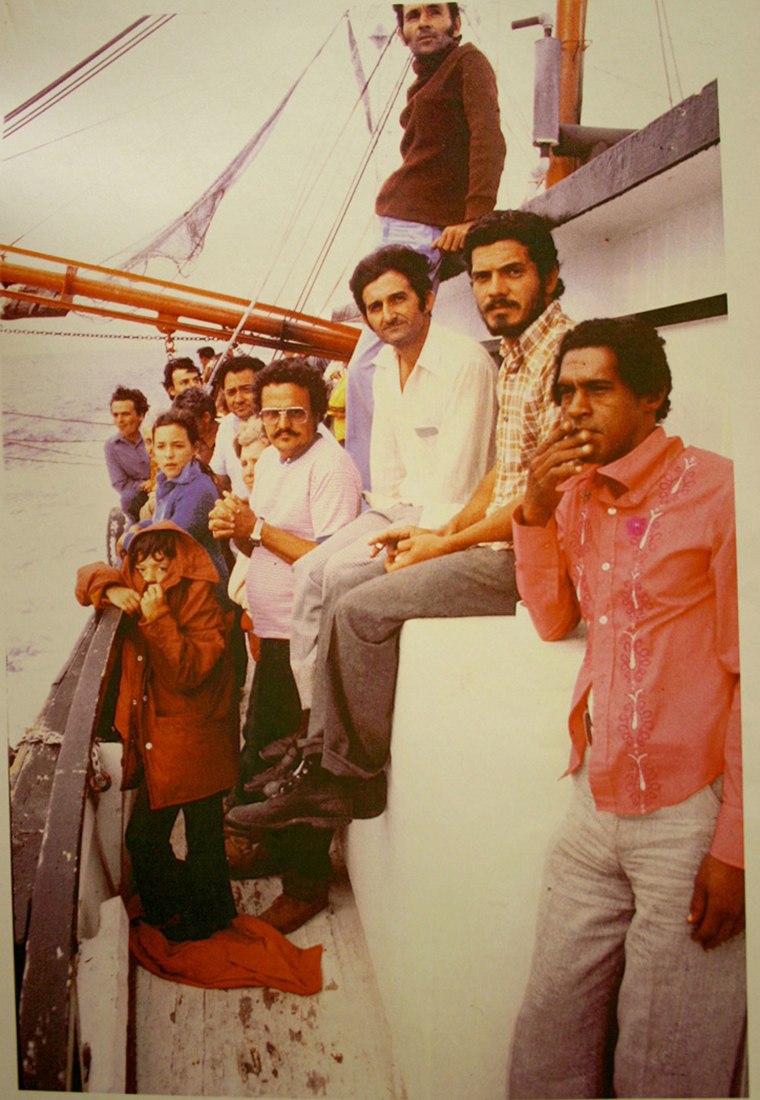

When Rodriguez and his family arrived in Cuba’s El Mosquito military holding camp near the port of Mariel, 25 miles west of Havana, he was just nine years old. It was April 24, 1980, and they—Rodriguez, his mother, father and sister—were among the first families to arrive to the camp, where all “Marielitos” were sent prior to boarding their boats.

Cuban President Fidel Castro announced, just days before, that anyone who wanted to leave the island could do so freely, so long as an exiled relative picked them up at the port. It was the start of the Mariel boatlift—a mass exodus that saw 125,000 Cubans leave their country over a six-month stretch.

Rodriguez’s aunt commissioned a boat to carry the family across the Florida Straits, but it would be a week between the time they arrived at El Mosquito and the time they boarded their vessel.

To relive the experience, as Rodriguez remembers it, is complex for the now 45 year-old. Sitting on the second floor of a raucous Manhattan Le Pain Quotidian at the lunch hour, he smiles as he thinks about playing baseball with other children in the camp—but the memory that comes to him is not without a subtle underlying disquiet.

“It was one of the most impressionable things in my life,” Rodriguez recalled on that windy, wet afternoon. “When I was a teenager in high school I made work about that… There were military tanks, barbed wire everywhere, the guards would come in and boss people around at any moment.”

"It’s political art in the most American way. A single person having an opinion."

Among Cuban-Americans, there is a stigma around so-called "Marielitos," with the operation considered a “Castrista” ploy to empty prisons and asylums and send the island’s worst to the United States—in retaliation for the American government’s treatment of Cubans who escaped, by boat, plane, or hijacking.

While there were criminals, the flight also comprised families, and it was the Cuban government’s disorganization that made it difficult to distinguish between the two kinds of refugees.

“They dropped everybody off in the same place—families, criminals, murderers, rapists, and prostitutes were all just thrown into an open area underneath some pine trees,” Rodriguez said. “I remember the first night we were there, in the middle of the night, they came in with German Shepherds trying to separate the families from the criminals.”

It was a problem of order, but also of resources. Rodriguez learned only recently that his father had gone the week without eating because of food shortages. The palpable strain throughout the camp was exacerbated by the Cubans’ uncertainty about their futures.

“There was always a tension in the air that you could be sent back home at any time,” he remembered. “And once you got sent back home, your life was pretty much over in Cuba.”

But Rodriguez didn’t get sent back home. Instead, 27 family members and friends boarded the Nature Boy on May 1, 1980. This early experience, he said, remains one of the first to influence all of the work he’s done since.

Having spent his youth in a small farm town called El Gabriel, embraced by fields of tobacco and sugar cane, Rodriguez also found himself stimulated by his neighbors, many were farmers without an education, who had a “simple wisdom” that now anchors his work. Ultimately, he said, that’s the goal: making simple images that co-opt fragments of the mundane, and twist them into mirrors that reflect their overlooked complexities, all while remaining accessible to the masses, regardless of class, education or profession.

The intention, he said, is to be consumable, but also to shock, and this wasn’t the first explosive cover the artist has illustrated.

The graphic design Rodriguez describes as his first real controversy was printed onto a 2015 Newsweek cover about women in the workplace and sexual harassment in Silicon Valley.

That didn't stop people from sending him hate mail or making threats

The cover ignited a public outrage that called on Newsweek’s editor, James Impoco, to come to its defense. He made the point that if the cover art made people angry, then perhaps it was exactly because they should be angry about the subject of the story.

In November, 2015, Rodriguez illustrated a TIME cover on the Paris Attacks, replacing the “I” in the magazine’s name with a blackened Eiffel Tower casting a somber, outstretched shadow across the rest of the page.

And long before either of these—or TIME’s “Meltdown” cover, or the image, for Der Spiegel, of Trump’s head as a massive fiery comet hurdling toward a diminutive earth, which is aligned just as to suggest it will soon be devoured—Rodriguez’s art was on the May/June 2006 cover of Communication Arts. The design took the iconic photograph of Che Guevara and added a Nike check mark to his beret and Apple iPod ear buds to the sides of his face—an especially testy cover that was ultimately shown even in Cuba, where Che’s image is venerated and nearly deified. Still, Rodriguez said, this cover of Trump severing the head of Lady Liberty was the first where the controversy persisted.

What was the difference this time? The answers to that question are manifold. The immediate, easy answers have to do with today’s heightened social media sharing culture—the capacity for virality—and the impact of major news outlets, according to the artist.

“I’ve been doing this for a long time, but I see the power of the big publication because I’ve done controversial covers before,” Rodriguez said, “but the minute the TIME magazine cover and Der Spiegel covers came out, they created an instant media firestorm.”

Some of the other answers are not as obvious at the outset but, once understood, reveal the nuance in his work.

This design came to Rodriguez as a composite of images he had already created, as a response to the immigration ban the president signed into effect on January 27. Subsequent stories of families being separated—Rodriguez recalled one that roused memories of the Elian Gonzalez showdown between Cuba and the United States in 1999—were all the fodder he needed.

“Castro would split families. Our families,” he said. “So I just thought ‘wow the president of the United States is doing the same thing that Castro would do.’ And he never said ‘I’m very sorry for the families that will be affected by this.’ There was no warning.

“These are humans,” he continued. “You can’t just do that to people. It’s his lack of empathy for anybody in any kind of situation.”

While Rodriguez admits he’d “rather be painting something else,” he acknowledges, too, as “an immigrant speaking to Trump,” the need to be politically engaged in our current moment.

The reality, he said, is that “we’re not fighting against Fidel Castro. We’re fighting against ourselves. And how do you win that fight? I think one of the ways is for me to do what I do.”

And in any case, he explained, he feels he is uniquely positioned to do this kind of work because his history sometimes acts as a protective barrier.

“You can’t come after me,” he said. “I have this experience and I’m an American now. I was affected in the same way these people are being affected now. What are you going to tell me about my life? Kellyanne Conway can’t tell me I don’t know what I’m talking about.”

But in some ways, responses to his cover were harshest in the Miami community of Cuban-Americans, where many share Rodriguez’s experience. Comments on Facebook and Instagram call him a traitor and propagandist.

“I think we are in a propaganda war, to some degree,” he said, adding as a disclaimer that his politics are “very middle of the road.” Nevertheless, he said, “I will fight this to the end because I’ve never seen someone be so awful to everybody.”

“What I do as a single man making from my soul and putting it out in the world,” he added. “It’s information. It’s political art in the most American way. A single person having an opinion.”

"It would be an insult to my parents if I shut up."

That didn’t stop people from sending him hate mail or making threats, and Rodriguez says security for the first time has become a concern. That, for him, only served as fuel.

“I’m actually shocked that I’m being asked ‘Are you going to be OK?’” Rodriguez said, responding with a half sarcastic, half bewildered tone: “Where are we?”

“I gave up my grandparents, I gave up all my friends. My family gave up so much to come here,” he continued. “And you’re going to sit there and tell me ‘Don’t say that? Be careful?’ No. It would be an insult to my parents if I shut up. Leaving Cuba affected me so much and I don’t take it for granted. I’m doing this because I had that experience and in this country no one should ever have to be quiet or not speak up. That’s what the American dream was to me.”

What good is your liberty, Rodriguez asks, if you can’t exercise it? And why is merely doing so deemed an act of bravery?

“I just wanted to speak my mind and make my art,” he added. “Now all of a sudden what I’m doing is brave and it really bothers me that I have to be considered brave to speak in this country.”

His work, he insists, is necessary to fight fire with fire.

“I believe that this man and his administration are so brutal that you have to be brutal back,” he said.

Perhaps the most thought provoking criticism Rodriguez received strikes with just one word: Blasphemy. It’s a notable choice because it’s likely that what the cover blasphemed, he thinks, was not President Trump but the Statue of Liberty. Though Castro was known to publicly reject all evidence of idolatry, it still plays a significant role in Cuban and Cuban-American daily life.

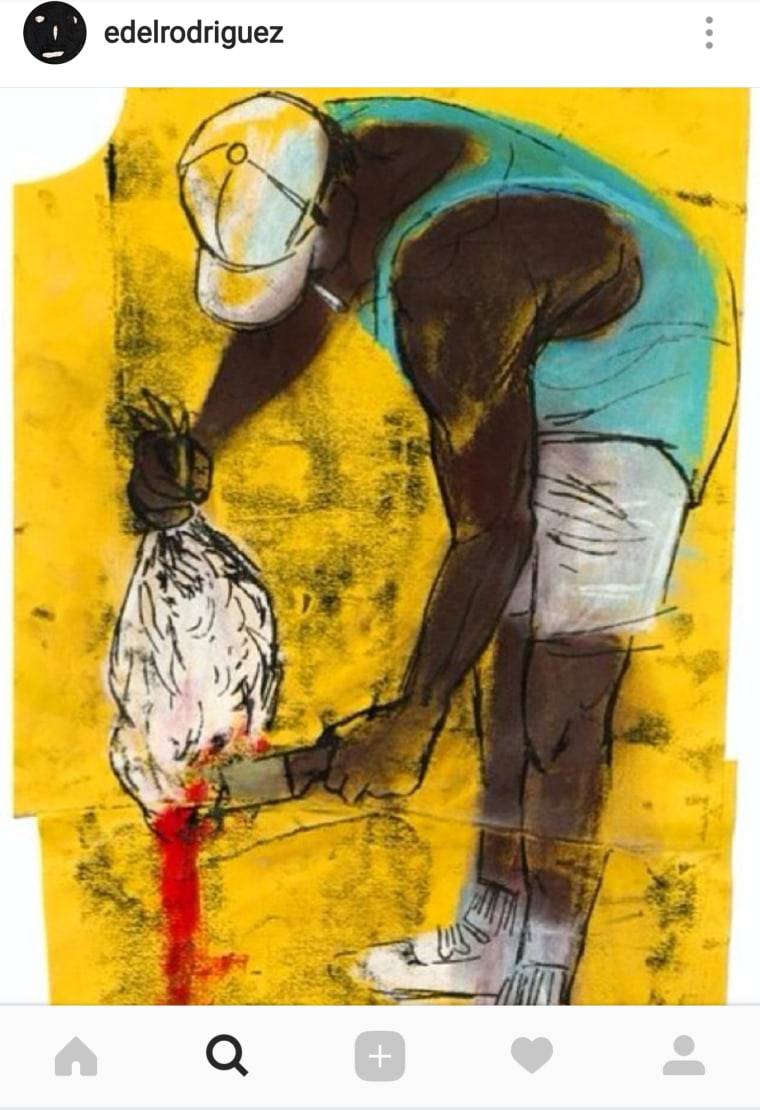

Statuettes casting saints like la Caridad del Cobre or la Santa Barbara into figures of tactile piety can be found in many homes. They are delicate and treated carefully, usually set alongside candles or, in Santeria, other offerings. The idea of decapitation and neck wounds too, it should be said, is not totally unusual in Cuban culture, considering that many grew up slaughtering their own cattle or poultry, or performing sacrificial rituals in religious practice.

Rodriguez, who said these figurines were also prominent in his home growing up, offered an example: His parents wanted to see the Statue of Liberty as a primary priority when they first visited him in New York, because, they said, “It’s America.”

This all-encompassing vision of Lady Liberty is not uncommon. In Spanish, Cubans use the phrase “La Mabel de Hierro” to refer to this very idea—that the Statue of Liberty is the symbol of America. In this sense, the elements of the design can be read as a suggestion that the Mother of Freedom, of exiles, the Lady on a Pedestal—and in effect, the virtue of American freedom and justice—had in fact become the offering in a sacrifice. The question here remains, a sacrifice to whom, and for what in exchange?

And so while the rest of the world focused on the depiction of Trump as terrorist, there’s reason to consider how some within the artist’s own diaspora might have been concerned about a defilement of the iconic symbol of freedom—the first view of the U.S. for most early immigrants who arrived on Ellis Island.

“Statues mean something to us,” Rodriguez reflected, acknowledging that in this sense, the charge of blasphemy is comprehensible.

As the country, and the news media in particular, continue to struggle with how best to deal with a Trump presidency that in the first hundred days seems to have insisted on unfolding with contention, Rodriguez has found a method, and is quickly becoming the person who is perhaps most speaking to Trump on his own terms—seizing a domain the president considers prime real estate: The coveted magazine cover.

“In a weird way it’s visually doing what he’s doing with words,” Rodriguez explained. “But I think it’s the only thing that he understands. It’s subversive but it’s in the biggest magazines in the world.”

By continuing to elicit significant global attention with his art, Rodriguez has weaponized the magazine cover not just as content, but as context as well, playing a nuanced subversive role that, in the simplicity of the images and the vastness of their mainstream production, might sometimes go overlooked. By allowing the public to use his images—as he did when he released them for free to those attending January’s Women’s March—Rodriguez takes the role of the image further, establishing it as a catalyst that mobilizes the otherwise hesitant.

“There are people who are too tired or scared or maybe on the fence to go to a protest,” he said. “And then they think ‘wow, look at this print. I’m going to make a poster of it and take it to the protest.’ It gives them some visual to work with. Something to share online. It’s kind of like a booster shot to people… and that’s the best that I can do is encourage people.”

While he concedes that today’s 24-hour news engine has a short memory, he says his job is to start the conversation, no matter how long it lasts. Sometimes when the momentum starts to lag, the solution is as simple as nudging the conversation along with a visual spur—in the trajectory of Rodriguez’s work, that’s the role of his newest cover.

In essence, when the conversation ends you start a new one. Though in between the release of the February and April covers Rodriguez has sustained dialogue by giving lectures, workshops and printing posters around the clock—many of which can be found posted along New York City streets. Now, Rodriguez is calling on other artists to do the same.

“If you look at everything the administration does every day, and everything they say, all the lies they tell... They’re trying to control information,” Rodriguez warned. “So I say if that’s the case every artist, everyone, should get on this and fight back through graphics and information.”

And when met with anger, take the advice Rodriguez’s father gave to him: “Si te joden, metenle mas.”