First 100 days are hard. Just ask Bill Clinton.

The 42nd president entered office without a popular mandate after winning just 43% of the vote in a three-way race with President George H.W. Bush and Ross Perot. He enjoyed a Democratic House and Senate, but soon found himself stymied by internal divisions and Republican opposition. He was slow to fill out his administration while his top aides argued over how best to right the ship.

When Bill Clinton hit the 100-day marker that the press has used to judge presidents since President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s New Deal, the reviews were brutal. His own budget director, Leon Panetta, warned he must do “a better job of picking and choosing the battles he wants to go through.”

All of this might sound familiar to President Donald Trump, who has struggled with many of the same problems in his first 100 days.

“This is the worst, least successful, first 100 days since it became a concept in 1933,” Jonathan Alter, an MSNBC analyst and author of “The Defining Moment: FDR’s Hundred Days and the Triumph of Hope,” said.

In evaluating Trump’s presidency and how it’s fared in relation to other new administrations, NBC News spoke to historians, activists, policy wonks, and former White House officials from both parties. Some, like Alter, raised Clinton’s early struggles as a loose parallel.

In Trump’s case, he has made no progress on major legislation, a development that’s especially troubling for a White House with unified control of government. His one significant item on the Hill, health care reform, crashed and burned. Instead, the president’s had to settle for more limited victories via executive orders, along with a successful Supreme Court pick that unified his party.

His foreign policy, punctuated by a surprise strike against Syria, is still unclear. The president’s approval ratings are historically low, with almost no honeymoon to speak of, and have often hovered around 40%. He’s rallied Republicans behind him and inspired a burst of economic optimism from his supporters, but shown little sign of winning over doubters outside his base. Trump has stuck to his campaign positions in some cases and abandoned them in others, raising questions about his overall policy vision.

Critics see a chaotic White House adrift without a clear plan for governance or the competence to carry one out.

“I think he has degraded the American presidency and introduced a greater degree of risk to the United States than any modern president,” Alter said.

But supporters say such judgments are premature, not to mention off base. They describe the White House as a work in progress that’s made a number of less-heralded moves that could pay off down the line.

“My experience is the president does things by trial and error,” Chris Ruddy, Newsmax CEO and a confidant of Trump, told NBC News. “Some people come in with a lot of strategic planning. Donald Trump likes to try things and see how they work, try people and see how they do.”

Clinton’s example offers both signs of caution and notes of hope for Trump. A shaky beginning set the stage for huge midterm losses as Clinton’s push for health care reform failed, his administration fought off distracting scandals, and his approval rating dipped into the 30s. But he also overcame those setbacks to win re-election and left office as a popular leader associated with an era of peace and prosperity.

Whether Trump will be able to match Clinton’s skill and luck is to be determined. Here’s what we know now about what his White House has done and how it operates as the president approaches his first major benchmark on Saturday.

Executive Leadership

The president’s biggest impact, for better and worse, has been at the executive level.

His first major executive order, a travel ban on a group of Muslim-majority countries, was shot down by the courts and hampered by poor management. Trump’s spent weeks engaged in a baseless personal campaign to prove President Barack Obama ordered illegal surveillance against him. His staff has been waging a continuous leak war that recently prompted Trump to publicly weigh in on infighting between his son-in-law Jared Kushner and adviser Steve Bannon.

But there are victories as well. Trump nominated and successfully confirmed Justice Neil Gorsuch, a popular consensus pick across the Republican Party. He withdrew from the Trans-Pacific Partnership, fulfilling a campaign promise, and approved the Keystone XL pipeline. Allies also point to the administration’s efforts to pare back regulations: EPA administrator Scott Pruitt’s early moves to dismantle Obama’s climate rules are a hit with small government conservatives even as experts warn they could lead to environmental disaster.

“They’ve had some real accomplishments in terms of the regulatory and administrative state,” Lanhee Chen, a fellow at the Hoover Institution who advised Florida Senator Marco Rubio’s presidential campaign, told NBC News. “These naturally fly under the radar a little bit more.”

On immigration, Trump has so far kept his promise to expand enforcement, opening up millions of undocumented immigrants to potential deportation that the previous White House sought to protect. Border apprehensions are down and it’s possible, if still unproven, that Trump’s harsher stance is a deterrent.

The overall picture, though, has been an administration bouncing between shiny objects without a clear focus.

Part of this reflects Trump’s heterogeneous choices in filling out his White House. There are rabble-rousing populists like Bannon and Attorney General Jeff Sessions, establishment figures like Chief of Staff Reince Priebus, along with movement conservatives like Vice President Mike Pence, Health and Human Services Secretary Tom Price, and Office of Management and Budget Director Mick Mulvaney. There are wealthy business leaders, like Secretary of State Rex Tillerson, Treasury Secretary Steve Mnuchin, National Economic Council director Gary Cohn and Commerce Secretary Wilbur Ross, along with a string of former generals, including Defense Secretary Jim Mattis and Homeland Security Secretary John Kelly. Finally, there’s daughter Ivanka Trump and her husband Kushner, who have each taken on broad roles.

While many of Trump’s picks have drawn praise individually, his early struggles raise questions about whether his government is too ideologically incoherent to enact his agenda. Trump railed against Wall Street on the campaign trail, for example, but the influential presence of former Goldman Sachs executives like Mnuchin and Cohn is already causing tension with his populist supporters.

Some Trump allies, however, see his Cabinet as a source of strength and several Republicans interviewed for this story mentioned that they admired his approach of seeking out varied opinions.

Jeffrey Sonnenfeld, a scholar on management at Yale University who Trump consulted during the transition, gave the president mixed reviews for his overall performance so far, but singled out the president’s blend of advisers for praise.

“Consensus is not a good thing,” he said. “Trump is instinctively brilliant in keeping some of that tension alive.”

To the extent Trump has stumbled, Sonnenfeld argued, it’s by not casting his net wide enough to include voices on the left. In this vein, the president blundered by alienating potential Democratic allies early on, especially Obama. In addition to the wiretapping accusation, Trump has regularly attacked his predecessor by name for alleged policy mistakes, something that sitting presidents are usually careful to avoid.

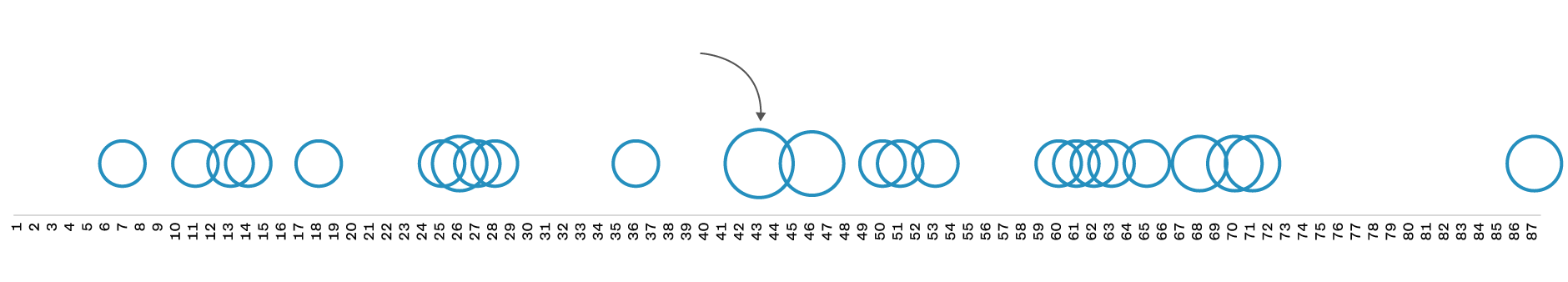

President Trump has Tweeted 36 times mentioning Barack Obama

DAY 43

Trump accuses Obama

of wiretapping Trump Tower

DAYS

DAY 43

Trump accuses

Obama of wiretapping

Trump Tower

DAY 1

DAY 87

DAY 43

Trump accuses Obama

of wiretapping Trump Tower

DAY 1

DAY 87

Sonnenfeld counseled Trump during the transition that former presidents had often served as critical advisers to their successors. “The needless assaults, finger pointing, accusations and insults hurled at his predecessor and the other side of the aisle are unfortunate,” he said.

Legislation

While Trump and his allies can debate his progress elsewhere, there’s little dispute that the president’s congressional agenda has been a wreck so far. His glaring failure to sign any major legislation or at least make significant progress on a signature bill stands out among modern presidents.

“It’s clear nothing’s really happening on the legislative front, other than Gorsuch, for the Trump administration,” Sarah Binder, a political science professor at George Washington University who researches Congress, told NBC News.

Even Clinton, who struggled mightily with a Democratic House and Senate in his first term, had some pent-up bills that made for easy victories early on, like the Family and Medical Leave Act, which President George H.W. Bush previously vetoed. President Jimmy Carter signed an economic stimulus package in his first 100 days. President Ronald Reagan was well on his way to securing a deal on tax cuts, as was President George W. Bush. Obama had signed his own stimulus bill, along with the Lilly Ledbetter Fair Pay Act and an expansion of the State Children’s Health Insurance Program.

Instead, Trump has had to settle for a handful of bills repealing regulations that were enacted at the tail end of Obama’s presidency.

There are a variety of factors behind Trump’s struggles in Congress, some of which are out of his control: Deep GOP divisions that the party papered over while opposing Obama, low approval ratings that give Trump less leverage than other new presidents, a lack of White House policy expertise, and a trend toward gridlock in Washington.

Donald Trump's Approval Ratings vs. Past Presidents

100% Approval

Trump trails every other

President in modern history.

80%

Barack Obama 67%

Ronald Reagan 66%

Jimmy Carter 63%

Lyndon Johnson 63%

George W. Bush 62%

60%

George H.W. Bush 57%

Richard Nixon 56%

Bill Clinton 55%

President Trump 43%

40%

20%

0

100 day mark

APPROVAL RATING

100%

Trump trails every other

President in modern history.

Ronald Reagan 66%

Jimmy Carter 63%

Lyndon Johnson 63%

George W. Bush 62%

60%

George H.W. Bush 57%

Richard Nixon 56%

Bill Clinton 55%

President Trump 43%

20%

100 day mark

0

100% Approval

Trump trails every other

President in modern history.

80%

Barack Obama 67%

Ronald Reagan 66%

Jimmy Carter 63%

Lyndon Johnson 63%

George W. Bush 62%

60%

George H.W. Bush 57%

Richard Nixon 56%

Bill Clinton 55%

40%

President Trump 43%

20%

0

100 day mark

Trump inherited a divided party that would have given any new Republican president fits, but he also entered office with unique opportunities. He ran against the GOP establishment in the primaries without much fundraising, which meant he owed less to interest groups. He regularly flip-flopped on key issues without any apparent consequences among supporters, which gave him room to maneuver. And many of his broad proposals crossed party lines, at least in theory. This was especially true on health care, where he promised no Medicare or Medicaid cuts, lower deductibles, and expanded coverage.

As a result, some backers were surprised that he chose to open with health care by delegating the task to House Speaker Paul Ryan, who seemed to embody the old Republican way of thinking that Trump ran against.

“I think Paul Ryan did a tremendous disservice,” Ruddy, the Newsmax CEO, said. “But the president was trying to work within the established framework. He was trying to bring people together. I think his job is to find a new center by bringing in most of the Republicans and getting a few moderate Democrats.”

The case for bipartisanship is clear enough. Trump’s instincts during the campaign were to promise a wider safety net that preserved entitlement spending, not an unyielding devotion to small government. His calls for $1 trillion in infrastructure spending are more in line with Democrats. Even on tax reform, Trump was torn during the campaign between giant tax cuts for wealthy Americans that his advisers cooked up and his boasts that he was willing to raise his taxes to help the middle class.

Listen to Benjy Sarlin's podcast with a leading presidential historian

“I think there is no natural coalition, it’s going to vary from issue to issue,” said Julius Krein, whose publication American Affairs is a clearinghouse for populist ideas in the Trump age. “If that’s even possible, if any administration can be nimble enough to do it, is tough to tell.”

But the right has a good argument, too: Many of them backed Trump early and stuck by him through tough times. Stylistically, their anti-Washington message fits his brand better even if their policy ideas sometimes contradict his promises.

“The conservative grassroots across the country were the ones who stood by him during the campaign in the general election and helped him get elected,” Jenny Beth Martin, a co-founder of Tea Party Patriots who met with Trump recently to discuss health care, told NBC News. “There’s certainly a coalition to work with there.”

While Trump’s lack of a fixed ideology make him well suited to court Democrats, his incendiary rhetoric and some of his hardline positions make him radioactive with their grassroots. That could make talk of working with Democrats a fantasy even if the White House decides it’s the best course.

“I think the way that Donald Trump campaigned by vilifying whole segments of the American community made it very difficult for him to then take office and reach out,” Heather McGhee, the president of the progressive think tank Demos, said.

McGhee said she was initially hopeful that she might find common cause with Trump on narrow issues like money in politics, which he railed against on the trail. Instead, he pursued the most divisive items on his agenda in the first 100 days, including a travel ban, health care repeal, and a crackdown on illegal immigration.

“He didn’t come out of the gate on jobs and infrastructure or trade, he came out of the gate on literally turning away our huddled and our tired and our poor, he came out of the gate taking aim at vulnerable people,” McGhee said.

Foreign Policy

Trump terrified elites throughout his campaign, but no one was more concerned about his presidency than foreign policy veterans of both parties who warned he could overturn the international order the United States had built up and led since World War II.

Heading into office, the president articulated an “America First” vision in which he threatened to shred longstanding alliances, withdraw from international institutions, launch a global trade war, and abandon almost all concern for human rights. All the while, he promised to pursue closer ties to Russian strongman Vladimir Putin and even publicly urged Russian spies to release Hillary Clinton’s emails in the midst of a hacking campaign against Democratic officials.

So far, though, it’s been difficult to divine what “America First” means in practice. Trump has already reversed a number of his foreign policy positions in favor of more conventional ones. Others, like his campaign pledges to negotiate trade concessions or impose new tariffs on rivals, have yet to take shape.

“This is a reality show host now understanding the reality of what he got himself into,” Nayyera Haq, who served in the State Department under Obama, told NBC News.

The ongoing confusion over how to define an “America First” policy peaked with Trump’s decision to launch a missile attack on an airfield in Syria over its use of chemical weapons on civilians.

While the move drew bipartisan praise, Trump had strongly opposed punitive strikes against the Bashar al-Assad regime after a chemical attack in 2013 and he spoke dismissively about humanitarian intervention throughout the campaign. Nor did he show much sympathy for refugees fleeing Assad’s atrocities, whom he likened to deadly snakes and tried to block from entering America as president. Days before the strike, Tillerson had said Assad’s fate was up to the Syrian people. Shortly afterward, the administration’s position was that Assad had to go.

Trump did not have a detailed background in foreign policy and his positions often appeared to follow the consensus among TV pundits: From pro-war to anti-war in Iraq, from pro-intervention to anti-intervention in Libya, and then from anti-intervention to pro-intervention in Syria.

Military matters aren’t the only areas where Trump has reversed himself. After pledging in campaign rallies to take a hard line with Chinese leaders on trade (sometimes with a mock Asian accent), Trump has more recently played up his “great chemistry” with President Xi Jinping.

During the transition, he took a call from Taiwan’s president and threatened to abandon America’s longstanding “One China” policy unless China made a trade deal on favorable terms. After taking office, he backed down almost immediately. Reneging on a major campaign promise, Trump also told the Wall Street Journal in April that the Chinese government were “not currency manipulators” after calling them a “world champion” currency manipulator just days earlier. In the same interview, he said he softened demands that China halt North Korean aggression thanks to a history lesson from Xi. “After listening for 10 minutes, I realized it’s not so easy,” he said.

The World According to Trump Who’s Up and Who’s Down

Russia

“

Mexico

“

NATO

“

China

“

Australia

“

Syria

“

As for Mexico, another frequent punching bag during the campaign, things have calmed down somewhat since President Enrique Pena Nieto cancelled a White House meeting in January after Trump announced an immigration crackdown. Mexico is still not paying for a border wall and there’s little sign the White House, which is asking Congress to fund it for now, will ever be able to make them do so.

On NATO, Trump decried the world’s most powerful military alliance as “obsolete” in January, then reversed himself and said it was “not obsolete,” but “the bulwark of international peace and security” at a joint press conference with its Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg.

Regarding another key ally, Israel, Trump punted on a promise that he would quickly move the American embassy to Jerusalem, signaled his opposition to new settlements in the West Bank, and seemed to loosen America’s longtime commitment to a two-state solution without abandoning the idea.

Trump’s much-discussed rapprochement with Russia has also yet to materialize. Instead, he said relations “may be at an all-time low” this month in the wake of his strike on the Putin-backed Assad regime.

And while Trump has criticized Obama’s nuclear agreement with Iran, his administration recently affirmed that Iran is complying with the deal. The president did complain they were violating its “spirit,” however.

“He made statements during the campaign that led you to believe he’d turn over the tea set,” Ambassador Mitchell B. Reiss, a veteran diplomat who advised Mitt Romney and John Kasich during their presidential runs, said. “There’s a more traditional balancing that is now taking place that should be reassuring to our friends and allies around the world.”

Tillerson, for his part, has isolated himself from the press compared to prior secretaries, thus minimizing his public role. Meanwhile, Kushner has taken on a broad foreign policy portfolio that includes the Israeli-Palestinian conflict and he recently visited Iraq.

“You can tell the priority of a business by where they put their money and where they invest resources and personnel,” Haq said. “Right now that is not the State Department.”

While the State Department struggles to get off the ground, Trump’s personal brain trust is looking more ordinary since he fired his divisive National Security Adviser Michael Flynn over undisclosed communications with Russia and removed Bannon from the National Security Council. Mattis and H.R. McMaster, who replaced Flynn as national security adviser, are widely respected figures in national security circles.

But the trend toward a more traditional foreign policy doesn’t entirely reassure observers. Some warn that the ongoing uncertainty, along with Trump’s habit of sudden outbursts, could prompt allies and enemies alike to misinterpret the White House’s signals in a tense situation — like the emerging standoff with North Korea over its nuclear testing.

“The North Koreans have to figure out when to take pronouncements literally and when to take them seriously,” Heather Hurlburt, director of New Models of Policy Change at New America, told NBC News. “I don’t really think they’ve got it quite down yet.”

Communications

On substance, Trump has sometimes veered off the course he laid out in the campaign. On style, he’s been wholly consistent.

From his first days as president, Trump has broken taboos about tone and civility, dismissed concerns about ethics and transparency, feuded with judges and the press, tweeted out conspiracy theories from fringe sources, and lashed out at the former Democratic nominee, whom he still refers to as “Crooked Hillary.” He launched his official 2020 re-election early and has held rallies similar to his 2016 events.

“It’s a complete carryover from the campaign in a way you historically do not see, whether in a Democratic administration or a Republican administration,” Cornell Belcher, a veteran Democratic strategist, told NBC News.

His inauguration speech, which railed against “American carnage,” set the tone early for a combative approach aimed at firing up core supporters. So far, his base loves it, his opposition is horrified, and Trump seems to enjoy egging them on in constant battle.

While other presidents have picked narrow agenda items and hit the road to focus attention on them with speeches, interviews, and events, Trump has acted more as a kind of roving commentator-in-chief who weighs in on topics as they catch his attention.

After suggesting during the campaign he might give up Twitter as president, Trump has instead made it his primary means of public communication, using it — with no apparent filter — to issue statements on everything from sensitive foreign policy matters to personal feuds.

The opinion of this so-called judge, which essentially takes law-enforcement away from our country, is ridiculous and will be overturned!

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) February 4, 2017

For eight years Russia "ran over" President Obama, got stronger and stronger, picked-off Crimea and added missiles. Weak! @foxandfriends

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) March 7, 2017

Arnold Schwarzenegger isn't voluntarily leaving the Apprentice, he was fired by his bad (pathetic) ratings, not by me. Sad end to great show

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) March 4, 2017

He’s both obsessed with his daily media coverage, often tweeting along with cable shows in real time, and enraged by it, deriding critical stories as “fake news” and reporters he dislikes as “the enemy of the people.” In a sense, he’s become a media outlet unto himself that speaks to supporters directly while bypassing traditional news and declaring outside scrutiny to be corrupt or illegitimate.

“There’s nobody who has been as dismissive of, not just the press, but any kind of factual check on him,” said Jay Rosen, a professor of journalism at New York University. “It’s much bigger than press relations, it’s the relationship to reality.”

Trump has reason to dismiss calls to change. He won the presidency despite historically low favorable ratings by rallying the faithful to turn out while convincing more skeptical Republican-leaning voters to at least stick along for the ride. His anemic approval ratings are just a continuation of that trend.

“He’s still effectively communicating with his base,” Jennifer Palmieri, who served as communications director on the Clinton campaign, said. “I think that they are more hopeful about the future, they think the economy is getting better, they think he is, in fact, making American great again.”

But it comes with a cost and at the top of the list is his administration’s credibility.

Trump and his aides have twisted, bent and broken the truth from their earliest moments in the White House, when Trump made false claims about his inauguration crowd size and then sent his press secretary, Sean Spicer, to defend them. Much of the last seven to eight weeks have been consumed by a manufactured crisis over Trump’s early morning tweets on wiretapping, which Congressional leaders from both parties and agency heads have repeatedly testified are not true.

Trump is also discovering that words have consequences as president in a way that’s not true as a candidate. Judges who have blocked his travel orders have cited his prior call for a Muslim ban and public statements by advisers in their decisions. His false claim that Obama illegally wiretapped his campaign sparked an international incident after his administration suggested British intelligence participated in the conspiracy.

In addition to Trump and his staff’s problem with the truth, the administration has often struggled to convey a unified message. Continuing another trend from the campaign, no one seems to speak for Trump but the man himself. Aides can put out statements on behalf of the president — a vote of confidence in a top official about to be fired, for example — only to be undercut by his own words and actions. At times, top officials have issued conflicting statements on sensitive matters, most recently Tillerson and UN Ambassador Nikki Haley on Syria’s future.

“It’s very difficult when you don’t have a message or the message only appears once the president says it out loud,” Republican strategist Reed Galen, who served in the George W. Bush administration, said. “It’s exhausting.”

Looking Ahead

Historians who talked to NBC News repeatedly stressed their unease with reading too much into the classic 100 days benchmark, especially as a predictor of future results.

“A president, in many ways, doesn’t have a lot of control over the period that their first 100 days falls in,” historian and MSNBC contributor Michael Beschloss said. “If you had to make direct comparisons, you’d have to grant them the same amount of peace or an economy in the same state.”

No matter how much I accomplish during the ridiculous standard of the first 100 days, & it has been a lot (including S.C.), media will kill!

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) April 21, 2017

“The chaotic first 100 days is more the norm than not,” Margaret O’Mara, a historian at University of Washington who served in the Clinton administration, said. “The only training to be president of the United States is on the job.”

President John F. Kennedy’s first 100 days ended in an iconic foreign policy disaster, for example: The failed Bay of Pigs invasion of Cuba. But he also learned from the experience, and the lessons helped guide him through the subsequent Cuban missile crisis.

“Crisis” is the key word. Presidents can go in with a game plan and the public can judge them on how well they pursue it, but more often than not they’re defined by unexpected challenges.

At this point in George W. Bush’s presidency, the best guess at his legacy would be a contested election and an impending tax cut rather than a terrorist attack, two wars, a hurricane, and an economic collapse. Carter was struggling with Congress, but remained popular throughout his first year before a revolution in Iran, an oil crisis, and stagflation made him the poster boy for hapless one-term presidents. If Obama’s White House had failed to contain the BP oil spill and Ebola outbreak, we might remember them as defining moments rather than footnotes compared to his legislative achievements.

Trump’s biggest setbacks so far have largely been internal failures rather than a response to an unexpected threat. But national security observers have fretted for months that his reliance on fringe rumors over intelligence reports, his public disregard for the truth, and his lack of policy knowledge could lead to disaster. Republican allies have also expressed concern about the White House’s slow pace in nominating and confirming appointees. It will be up to Trump to prove his doubters wrong when his test, whatever it may be, finally comes.

“The most important thing you can do in the White House is deal with problems when they’re the size of acorns rather than when they become giant oak trees,” John Sununu, former governor of New Hampshire and White House chief of staff under President George H.W. Bush, said.

At the same time, Trump faces a difficult path forward on his planned agenda. Enacting tax reform and an infrastructure package, two of the biggest items, will be daunting tasks. His executive orders could eventually lead to major changes in regulation, but they’ll face a long rulemaking process and legal challenges first.

Looming over everything is an ongoing FBI investigation into his campaign’s possible ties to Russia. Already the president has had to oust Flynn for misrepresenting his conversations with Russia’s ambassador and Attorney General Jeff Sessions has had to recuse himself for failing to disclose contacts with the same ambassador.

If Trump’s not careful, he could also run into scandals related to his failure to divest from his company and release tax returns and financial information that could shed light on potential conflicts.

For now, though, Trump has the luxury of both time and flexibility to correct his course.

Bill Clinton may be a model in this regard. After several months of missteps, he brought in veteran figures like David Gergen, who had served in three Republican administrations, to help calm the waters. When his push for health care reform failed, he experimented with new coalitions and found ways to triangulate between his party and a Republican Congress, which served as a legislative partner at times and as an overreaching nemesis at others.

And if that fails, he can take comfort: The final judgment is a long way off.

“I remember what George W. Bush often said when asked how historians would view him,” Tevi Troy, a historian who held multiple positions in the Bush administration, said. “He would say, ‘They’re still writing books about the first George W.’”