MOSCOW -- We winced in our filthy trench as each rocket-propelled grenade whistled overhead and exploded behind us. It looked like World War I.

About 100 yards across a no-man’s land and barbed wire, ethnic Romanian soldiers from Moldova were dug deep into a wooded area, firing rusty munitions from a Red Army arsenal left behind after the fall of the Soviet Union a year earlier.

It was the spring of 1992, and it was weird. I kept thinking we were going to die in a trench in the middle of nowhere and no one would ever know. Not far away from the surreal front line, farm workers plowed their wheat fields during lulls in the shelling.

Post-Soviet mayhem was just beginning back then.

Fast forward to today. Russian forces are once again amassed in big numbers in the neighborhood.

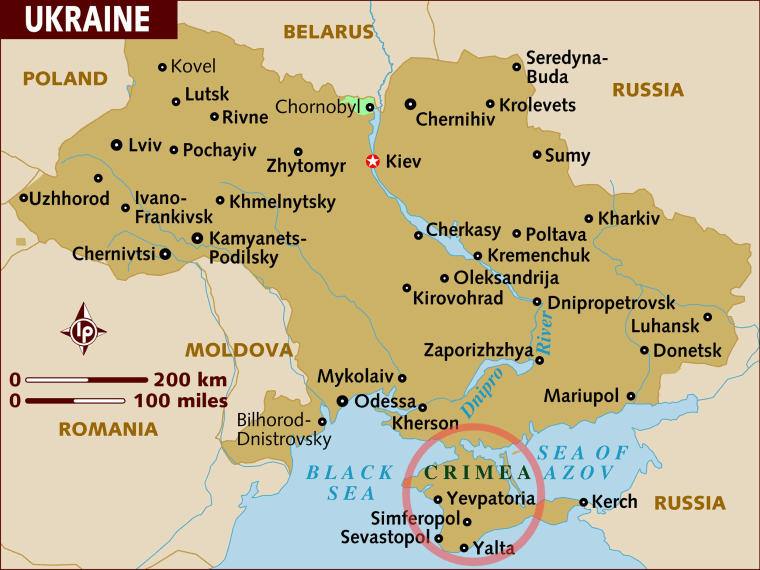

This time about two divisions – some 20,000 infantry, airmen and special operations forces – are poised along Ukraine’s eastern border with Russia, ready to intervene if ethnic conflict endangers large concentrations of Russian speakers in Ukraine’s southern and eastern regions.

And again, trenches are being excavated. Billionaire Sergei Taruta, who was recently appointed governor of Donetsk province by the new administration in Kiev, is reportedly financing a 120-mile-long anti-tank ditch near the border with neighboring Russia.

Matthew Clements, who heads the Europe and CIS country analysis team at IHS, said that armed conflict between Russia and Ukraine is still a risk in the wake of Vladimir Putin's annexation of Crimea.

He believes any Russian intervention into areas with large numbers of ethnic Russians - including the cities of Luhansk, Donetsk, Kharkiv, Zaporizhiya and Kherson - would "rely on speed and shock to establish control ... before Kiev or the West can fully respond."

But even these areas - unlike Crimea - are mixed with equally large numbers of ethnic Ukrainians, and any invading Russian troops would face opposing "self-defense" militias which would ''likely seek to conduct guerrilla warfare.''

It is reminiscent of across the Moldovan border in 1992.

My NBC News team –- producer Justin Balding and cameraman Kyle Eppler -- had been moving with ethnic Russian militiamen. These former Soviet soldiers had carved a patch out of rural Moldova and called their new Russian state "Trans-Dniester" –- literally "beyond the Dniester River."

And these Russian-speaking "Transdniestrians" were firing other rusty RPGs from the same old Red Army arsenal right back at the Romanian speakers.

"Suddenly the UN’s armored personnel carrier was fired on ... We drove through the front lines with a white flag flying"

Several months later, Slavic UN peacekeepers arrived in Trans-Dniester to keep apart the Russians on the east bank from the Moldovans on the west bank of the river, hoping a tenuous truce would hold.

"We were out on a UN patrol and suddenly the UN’s armored personnel carrier was fired on and all the troops ducked inside the vehicle," recalled Balding. "After that we drove through the front lines with a white flag flying."

The localized fighting intensified, until then-Russian President Boris Yeltsin sent in a an army unit who opened fire on the Moldovan forces.

After the dust settled, and the bodies counted, a cease-fire was signed and the Trans-Dniester Republic was still-born – landlocked, the size of Rhode Island, home to about 200,000 ethnic Russians and hundreds of Russian troops who called themselves "peacekeepers." No nation recognized it. Not even Russia.

Tensions simmering for years in Moldova have again returned to the surface. The threat of violence is real there.

After witnessing the fast-tracking of Crimea’s annexation, Transdniestrians are themselves demanding to be recognized.

Earlier this week, Mikhail Burla, Trans-Dniester’s Speaker of the Parliament – yes, it has its own legislature, military, police force and kitschy national anthem - traveled to Moscow to meet with his Russian counterpart and appealed for formal annexation by Putin.

In a scenario uncannily similar to that of Ukraine, Burla explained that the pro-Western government currently in power in impoverished Moldova planned to sign an association agreement with the European Union, angering the ethnic Russians in Trans-Dniester.

The following day, Moldovan President Nicolae Timofti warned Russia that Trans-Dniester was an illegal body and that annexing it would be "a mistake," according to The Moscow Times.

It took little time for Senators John McCain and Lindsay Graham to warn the Obama administration of this other flashpoint on the heels of the Crimea debacle.

"Through its weak and inadequate response to President Putin’s land grab in Ukraine, the West is in danger of acquiescing to Russian efforts to redraw the borders of Europe through military force," the Republicans said in a statement. "Our friends in Moldova - as well as the Baltic countries and every other country with ethnic Russian populations - are right to be concerned. The West must impose real costs on Russia for its aggression in Ukraine. By failing to do so, we only invite further aggression elsewhere."

But the drums of annexation are beating on. Putin's Deputy Prime Minister Dmitry Rogozin – who now finds himself on a U.S. list of sanctioned individuals – called for an emergency conference amid reports that Ukrainian border guards had blocked Transdniestrians with Russian passports from entering neighboring Ukraine.

Despite the saber-rattling, there’s still no indication that Putin actually wants to absorb the tiny land often called a "mafia state," which owes billions of dollars in energy debts to Russia.

Unlike in Crimea, the Russian compatriots of Transdniester live far from the Motherland.

"There's just no physical possibility for Putin to easily control it," said Russian affairs analyst Fyodor Lukyanov, editor of the "Russia in Global Affairs" quarterly. "Transdniester is separated from Russia by a big, hostile territory called Ukraine. How do you deal with that?"

But other voices say that Putin’s annexation of Crimea is a game-changer. "There’s little doubt that the Kremlin will, from now on, certainly take notice when Russian speakers clamor for the salvation of the mother country," wrote Bloomberg Businessweek journalist and author Jeffrey Tayler.

Whether the next clashes ignite in the industrial swaths of Ukraine’s Kharkiv, or Donetsk or beyond, in the backwater of Transdniester - ethnic Russians across the former Soviet Union now feel inspired by the promise of Crimea to stand up and fight.

JIm Maceda is a London-based NBC News foreign correspondent who is currently on assignment in Moscow. He covered the former Soviet republics extensively during and after the fall of the U.S.S.R.