The pictures are hard to look at.

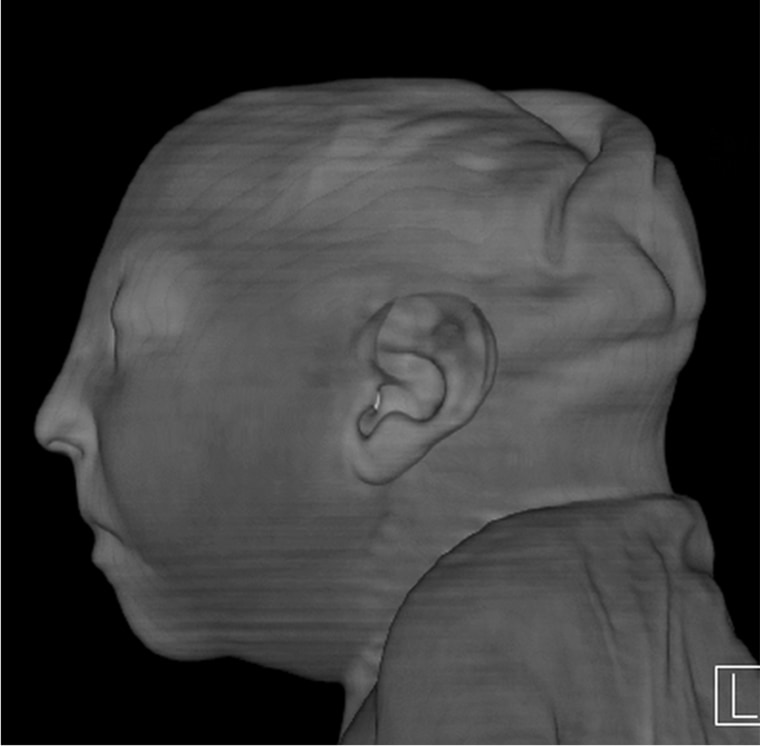

Rough ridges appear where a baby’s soft skull should be round and smooth. Inside, big patches of white show where brain tissue should be, and isn’t.

Brazilian and American doctors released a package of scans Tuesday showing the range of destruction that Zika virus can wreak on a developing child. Their aim isn’t to horrify, but to help educate radiologists and other specialists about what they need to be on the lookout for as Zika spreads across the Western Hemisphere.

Pregnant women, or women who might become pregnant, are being cautioned to stay away from Zika zones if at all possible, per guidance from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the World Health Organization. But not all women can — especially if they live there.

And the women whose babies are included in the special report in the journal Radiology were affected before WHO and CDC warned the world of the danger caused by a virus that experts all believed was harmless until last year.

The virus is being spread locally in three places in Florida — Miami Beach, an area north of Miami and now in the St. Petersburg area. Health officials expect more U.S. outbreaks.

"The first trimester is the time where infection seems to be riskiest for the pregnancy."

Brazil has now reported more than 8,000 cases of microcephaly and confirmed that women were infected with Zika in more than 1,600 of them. It’s harder to test people for Zika infection after they’ve recovered.

Dr. Fernanda Tovar-Moll of the D'Or Institute for Research and Education and the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro in Brazil and colleagues examined some of them.

They found a large range of birth defects, from missing brain tissue to deformed limbs. But they focused on what could be seen in images of the brain before and after birth.

Related: Zika Took Her Baby. She's Worried About Other Moms

Not all babies are born with the characteristically small head, a condition known as microcephaly, they said. Some babies may have brains damaged later in pregnancy, or may have swelling called ventriculomegaly that keeps the growing skull supported so that they appear physically normal at birth.

Some may look perfectly normal, yet have extensive brain damage.

Others have skull deformities caused as the virus destroys brain tissue while bones are still forming.

“The striking imaging features of the severe micrencephaly associated with Zika virus include a markedly abnormal head shape,” the team wrote.

“The unusual appearance of the skull, we hypothesize, is due to a combination of the small brain as it develops and a result of what, at some point, was likely a larger head size (due to ventriculomegaly) that then decompresses,” they added.

There are also strange ridges and projections on the heads of some babies and fetuses. “This is also likely due to the head and skin continuing to grow, while the size of the brain regresses,” they wrote.

As suspected, the earlier a woman is infected in pregnancy, the worse the damage is. Zika is the first mosquito-borne virus to cause birth defects but other infections are known to cause similar damage –including rubella and cytomegalovirus. But Zika’s damage appears to be worse than the damage caused by other infections, the team said.

Related: Can I Ever Get Pregnant After Zika?

"The first trimester is the time where infection seems to be riskiest for the pregnancy," said Dr. Deborah Levine, the director of Obstetric & Gynecologic Ultrasound at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center and a professor of radiology at Harvard Medical School in Boston.

The team included 438 patients seen from June of 2015 to May 2016. Of them 17 of the babies were confirmed to have been infected with Zika.

The damage did not always immediately show up. The CDC now recommends that pregnant women who have had Zika or suspect they were exposed to it have a series of ultrasounds throughout pregnancy.

"More than one ultrasound or MRI scan in pregnancy may be needed to assess the growth and development abnormalities of the brain," Levine said.

Zika appears to stay in the bodies of developing babies, doing damage over weeks and months. It may also stay in the brain after birth, or at least continue to affect brain development, the researchers said.

"We are also interested in investigating how congenital Zika virus infection can interfere with not only prenatal, but also postnatal gray and white brain maturation," Tovar-Moll said.

What researchers cannot predict is exactly how the brain damage will affect a child – if the baby survives.

“We can’t say this baby will survive or not survive or if they survive this is how disabled they are going to be."

“The reality is with all of the technology that we have you can’t tell someone that this is what’s going happen to your baby,” said Dr. Roberta DeBiasi, who helps head the Congenital Zika Virus Program at Children’s national health System in Washington, D.C.

“We can’t say this baby will survive or not survive or if they survive this is how disabled they are going to be. We just don’t have that precision.”

Related: New Studies Show Zika's Tricks

Doctors also cannot yet say what percentage of women infected with Zika will have a baby with birth defects. And they cannot say whether the odds are worse if a woman has symptoms from Zika. At least three-quarters of those infected don’t remember any specific symptoms.

In this study, the team found that more than 80 percent of the women infected in the first trimester of pregnancy who had Zika-affected babies had the characteristic Zika rash. But they stress their group doesn’t represent the population as a whole.

“Thus, we have no information on incidence of the Zika virus in the general population or risk estimates for transmission to the fetus,” they said.