Now that the White House has surrendered to the Republican-led Congress and taken half a billion dollars from other projects to fight the Zika virus, here’s some things to know about the mosquito-borne illness.

Where did Zika virus come from?

Zika was first noticed in Africa, in Uganda’s Ziika forest (yes it’s spelled with two i’s) in 1947. It spread slowly at first, and seemed to be a pretty harmless virus, causing hardly any symptoms at all in most people. But it picked up speed in around 2007 when it started spreading in the South Pacific and it showed up in Brazil in 2013, according to the latest research. Because hardly anyone in the Americas has immunity to Zika, it’s spread explosively since then.

What does it do to people?

Most people barely notice they have an infection. It causes a rash in about 90 percent of people who notice it, along with headaches, muscle aches and fever. It’s also clear that it can cause birth defects. When a pregnant woman gets infected, the virus can get into the developing fetus, damaging the brain and causing a condition called microcephaly in which the head is too small. It’s also clear it causes other types of brain and nerve damage and can cause babies to miscarry or die at birth.

The World Health Organization says it’s also almost certain the Zika virus, like others, can cause Guillan-Barre syndrome, a paralyzing condition that usually isn’t permanent but which can disable people for months or years. It may also cause other nerve damage, including a brain inflammation called encephalitis.

How does Zika spread?

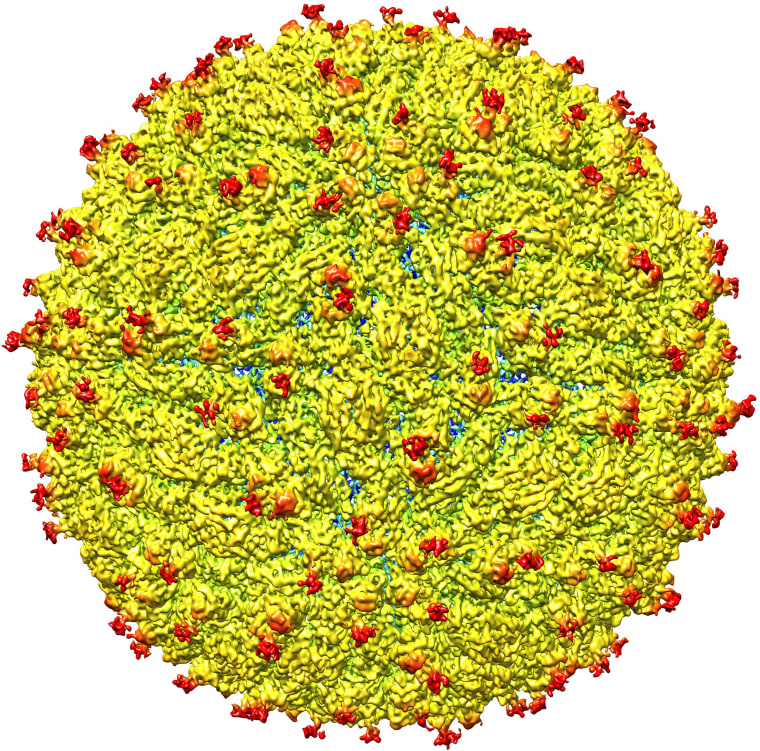

Mostly by mosquitoes – specifically, the Aedes aegypti mosquitoes that thrive in tropical zones. They’re called the “cockroach of mosquitoes” because they love to live inside people’s houses, thrive in squalor and are really hard to kill. A female Aedes mosquitoes can sip blood from a roomful of people, and if it's infected, it can pass the virus to everyone.

The virus is also sexually transmitted, which is why the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention cautions people to use condoms after they’ve been to a Zika-affected zone. Pregnant women whose sex partners have been in an affected area need to use a condom for the whole time they are pregnant, because no one’s sure how long the virus can stay in a man’s semen.

The virus is also found in urine and saliva, but it’s unclear if it spreads that way. Scientists have debunked the notion that insecticides or genetically engineered mosquitoes are causing the problems blamed on Zika.

Will Zika come to the U.S.?

It already has. The CDC says close to 700 people have been infected, mostly travelers from affected regions. Puerto Rico is the worst hit because it has the Aedes mosquitoes year round and also has a lot of poverty. The Aedes aegypti mosquitoes are very common in south Florida, south Texas and the Gulf coast but they’re found in summer as far north as San Francisco, Kansas City and New York, so all those areas can expect at least small local outbreaks in the summer.

More than 40 million people come back and forth from Zika-affected areas every year so CDC experts say many of them are likely to bring the virus with them. But they say outbreaks should be limited, because Americans use air-conditioning and screens – both of which stymie the mosquitoes. Nonetheless, officials are urging good mosquito control measures and say people should protect themselves from bites with clothing, repellants such as DEET, insecticides and by staying indoors.

Will there be a lot of babies with birth defects?

There already are. Brazil has recorded more than 4,000 cases of microcephaly in the past few months. There’s a documented case of a U.S. baby born in Hawaii with microcephaly whose mother had Zika while pregnant. Several babies that miscarried or were aborted because of severe brain defects also have been shown to have Zika in their bodies.

Why does the White House want so much money for Zika?

The White House has asked Congress for $1.9 billion for the Zika fight. The National Institutes of Health wants money to develop a vaccine, to look for better tests for Zika and to work on treatments for the virus. The CDC wants money to figure out just how many pregnant women have been infected, whether it matters what stage of pregnancy a woman is in, and what percentage of pregnant women who get infected will end up with affected babies. States want money to help eradicate mosquitoes and to prepare hospitals to deal with Zika patients. And the Health and Human Services Department says babies born with birth defects will need millions of dollars in care.

Conservatives in Congress say the money should come from elsewhere because taxpayers are already overburdened, but CDC, NIH, HHS and the White House say there really isn’t any leftover money anywhere. They say money allocated for Ebola is already spoken for and needed to build up health systems in developing countries so that yet another virus doesn’t come seemingly out of the blue to infect people around the world, including in the U.S.