On the evening of Sunday, Aug. 9, workers at the MKE1 Amazon fulfillment center in Kenosha, Wisconsin, received an alert from the company via text message: More of their colleagues had tested positive for the coronavirus and they needed to maintain social distancing. They’d received about three of these notifications a week in the preceding four weeks.

The next day, the National Weather Service issued a tornado warning for the county. Managers ushered hundreds of employees into windowless rooms where they huddled shoulder to shoulder for half an hour, waiting for the storm to pass.

“They were just shoving people into the breakrooms, easily over 200 in each one,” one current employee said through tears. She spoke on the condition of anonymity because Amazon workers are not allowed to speak to the press. “They didn’t have a plan. There was no social distancing, none whatsoever,” she said.

But if that half-hour in a packed room led to additional Covid-19 cases among her co-workers, she has no idea. The local health authorities don’t appear to know either. The company declined to provide data about the total number of cases in the warehouse despite repeated requests by health department officials, according to over 700 pages of internal correspondence from the Kenosha County Division of Health obtained by NBC News under Wisconsin state public records law.

Kenosha County’s health director, Dr. Jen Freiheit, described Amazon as “less than easy to work with” in an email sent to a colleague in May, referring to efforts to find out how many workers had tested positive for Covid-19.

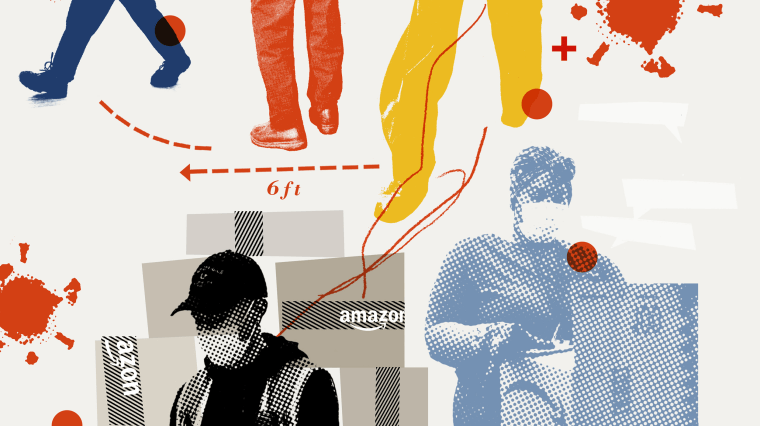

Amazon’s lack of transparency, combined with the lack of federal protections for U.S. workers who contract infectious diseases in the workplace, make it almost impossible to track the spread of Covid-19 at one of America’s largest employers during a coronavirus-led boom in online retail. This has left some of its 500,000 warehouse workers at its 110 U.S. fulfillment centers — deemed essential during lockdown — attempting to fill the information gap.

Information from health authorities is also lacking. NBC News contacted 25 health departments with high concentrations of Amazon fulfillment centers and other logistics warehouses in 16 states asking for records of Covid-related workplace investigations and inspections in warehouse facilities and email communication with Amazon. The responses were varied, with only a handful of health departments providing relevant records.

Only five departments provided relevant records about workplace investigations and inspections. Two rejected requests on the basis that the records would contain confidential information that could “harm a person or business,” while one said it was too busy to process records. Of the rest, six acknowledged the request but did not respond within two months, five said they had no responsive records — including Luzerne County in Pennsylvania, where workers at the APV1 facility in Hazle Township counted at least 81 cases — while two did not acknowledge the requests.

NBC News also requested emails exchanged between Amazon and those health departments. Seven returned relevant records, four returned irrelevant records and four said they had no responsive records. Five health departments said they needed more time; four acknowledged the request but never responded; while Harris County, Texas, said it was too busy to process records.

Amazon's employees also said they don't have much information. NBC News talked to 40 Amazon employees from 23 facilities who said that many of the safety measures Amazon enacted at the start of the pandemic are either no longer active or difficult to enforce. They also said that without more detail from Amazon it was difficult to make informed decisions about the safety of coming into work. Some have started tracking positive cases of Covid-19 in their facilities themselves through Facebook groups and spreadsheets.

Amazon's lack of transparency is compounded by what occupational health experts describe as inadequate legal protections — including inaction from the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) — that have left employees of Amazon and many other employers with few protections and little information about outbreaks they face at work.

Amazon spokesperson Lisa Levandowski said that the company had prioritized the risk of a potentially life-threatening tornado in Kenosha, following guidance from FEMA, and that there hadn’t been any increase in cases linked to the event.

Levandowski said Amazon also reports all positive cases of Covid-19 among workers to the health department where the worker lives, but doesn’t release total cases broken down by facility to avoid creating “unnecessary fear.”

“We believe that sharing a case count is misleading, and lacks a significant amount of context — like when each individual was last onsite, the overall infection rate in the community where the site is located, community data relative to where the associate lives, timelines since the start of the pandemic and the overall rate compared to other companies,” she said.

Inside Amazon

In late March, Jana Jumpp, then an Amazon employee at an Indiana fulfillment center, started working with other Amazon workers across the country to start figuring out how many warehouse workers were contracting Covid-19.

Jumpp, who quit her job in July, said she started the project because she believed Amazon wasn’t providing workers with enough information about cases to make informed decisions about coming into work during a pandemic.

“Someone else needed to keep score," she said.

Since then, she and a group of volunteers have spent time in Facebook groups for warehouse workers collecting screenshots of notifications of positive Covid-19 cases. They added the cases to a spreadsheet, creating the fullest public picture of how the pandemic has spread within Amazon warehouses in the United States.

According to Jumpp’s data, there have been 2,038 positive cases and, according to NBC News’ own research, at least 10 deaths, which Amazon confirmed. There may be more cases, however, because this estimate is based on the notifications that Amazon sends employees when there have been new positive cases. These notifications disclose multiple new cases but do not specify whether that means two cases or 10. Jumpp counts these notifications as two cases.

As a comparison, United for Respect, a worker advocacy group, has collected data about Covid-19 cases and deaths among Walmart’s 1.5 million workers in the United States. According to worker-submitted data there have been at least 1,497 reported cases and 22 deaths.

Walmart did not respond to a request for comment.

The lack of information about the scale and severity of coronavirus outbreaks in Amazon fulfilment centers across the U.S. stems from a combination of vague communication from Amazon to its workers and little to no requirements from local and national regulators to report the number of positive coronavirus cases among workers at their facilities.

Amazon workers said that they’re only receiving vague information from the company about positive cases at work in text messages, emails and an app used by workers.

“The texts we get distinguish between whether there was one case or multiple cases found that day, but that’s as specific as it gets. You don't know whether they were on your shift or in the same section as you,” said John Hopkins, who works at the DSF4 Amazon fulfillment center in San Leandro, California.

NBC News reviewed dozens of screenshots of these notifications shared by workers. They flag that a worker or multiple workers have tested positive in the facility and the date they were last on site. The company says it will “proactively reach out” to those who have been in contact with sick employees, but workers weren’t aware of this happening.

“To my knowledge no one in my facility was even told they were close enough to a positive case to quarantine, and it’s a pretty small facility, so it seems impossible that no one came into contact with one of the people who was sick,” Hopkins said. “It seems to me that they’re not even contact tracing”.

Amazon said it kept the notifications vague for privacy reasons and that it used a camera surveillance system called “Distance Assistant” to detect workers who had been within 6 feet of an infected worker for at least 15 minutes for contact tracing purposes. The company also said that it asks sick workers questions about contact outside of work, including carpooling and cohabitation, and that only a small proportion of workers met these criteria.

But that has done little to quell concern among some employees like Jumpp who said they felt the need to take matters into their own hands.

“I hope workers understand that they have power in numbers and they need to not be so trusting that a company is going to do the right thing,” Jumpp said.

Little oversight

Amazon may not be offering much in terms of information about coronavirus cases, but many local health departments are doing little to change the situation.

In Pennsylvania, the state is not conducting inspections or collecting information about outbreaks at any warehouse facilities that are not “food related,” according to interviews with the state health department’s press secretary, Nate Wardle, and deputy press secretary, Maggi Mumma. There’s no requirement to report and no data being collected, they said.

Jumpp said her group has recorded at least 81 cases in Hazle Township, Pennsylvania.

Other states have done more, and some counties were satisfied with Amazon’s response and communication.

A spokesperson for Middlesex County, New Jersey, said that it conducted a “thorough investigation” of Amazon facilities in the towns of Carteret and Edison in late April after workers documented more than 44 cases between them, and gave the site’s leadership specific directions to ensure a “safe and healthy work environment.” The county followed up in May to find Amazon had implemented the CDC guidelines, as directed.

Lisa Brodsky, the director of public health for Scott County, Minnesota, said Amazon calls her team every Thursday to exchange information about cases “and they have been wonderful to work with.” Amazon's Shakopee facility in Scott County had at least 186 infected cases of Covid-19 through Sept. 8, according to state health department data. The rate at the facility exceeded the community infection rate, according to an internal memo obtained by Bloomberg News, contrary to the company’s repeated public statements, including to NBC News, that cases in its facilities across the United States were in line with cases in the local area.

However, in Kenosha, where the Amazon workers were stuffed shoulder-to-shoulder in a tornado shelter, email records show health department officials were frustrated with Amazon’s “less than helpful” attitude in March.

Several weeks later, on May 9, Freiheit, the Kenosha County health director, reiterated her frustration with Amazon, noting that the company would only provide information about cases involving Kenosha residents and not total cases in the facility.

Kenosha’s MKE1 facility, according to Jumpp’s count, represents the third-highest count of infected workers at an Amazon fulfillment center.

County officials toured MKE1 in late May and Freiheit told Amazon “what we saw was positive,” but called on the company to be more transparent with its infected cases.

Six weeks later, Freiheit again lamented Amazon’s lack of transparency.

“We are having trouble with communicating to Amazon again,” she wrote on July 15. “We need to be doing the contact tracing and have not been receiving communication that gives us the names of close contacts.”

Amazon said that it has started a voluntary testing program for workers at facilities in Kenosha.

Little recourse

Several occupational health experts pointed the finger at OSHA for failing to track Covid-19 outbreaks in the workplace and for not penalizing companies that don’t keep workers safe.

Occupational safety standards in the U.S. are more geared to workplace injuries than preventing the spread of infectious diseases. Positive cases that are reported to local health departments from workplace coronavirus testing require logging where the person lives, but not where they work, despite the likelihood of workplaces being a major vector for contracting the virus, per guidelines from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

“If we want to stop this virus, we collectively have to be able to keep workers safe and we have to know when people are getting exposed at work,” said Terri Gerstein, senior fellow at the Economic Policy Institute, a labor-funded think tank, and director of the State and Local Enforcement Project at Harvard Law School’s Labor and Worklife Program. “It's just layer upon layer of inadequacy in terms of taking the steps needed to protect people.”

OSHA requires companies to report illnesses and injuries that are work-related, but studies have shown employers routinely underreport these. This is particularly true with infectious diseases like Covid-19, experts said, since it’s difficult to prove a worker was infected at work.

Even if OSHA were effectively collecting data on workplace outbreaks, the enforcement agency lacks the teeth to penalize employers, because it has no specific rule about protecting workers from infectious disease. The agency was in the process of making one under the Obama administration, but federal workplace safety rules take years to promulgate, and efforts were paused after President Donald Trump took office in January 2017. Attempts to introduce an emergency infectious disease rule when the pandemic arrived in the United States were also set aside.

“OSHA has always been a very weak agency, but this administration has elected not to use some of OSHA’s most powerful tools,” said David Michaels, who was the head of OSHA under the Obama administration, referring to the agency’s failure to introduce an infectious disease rule.

Robert Harrison, a clinical professor of occupational medicine at the University of California, San Francisco, said that the pandemic “couldn’t have happened at a worse time for the health of American workers.”

“Federal OSHA is asleep,” he added. “The pandemic and its effect on workers is the largest public health crisis in my lifetime and if there was ever a time for there to be an awake, aggressive and alert federal OSHA, now is it.”

Instead of regulation, OSHA has issued guidelines to employers on how to protect workers from Covid-19.

OSHA maintains that these guidelines, along with existing law, are sufficient to protect workers. However, it has done little enforcement. The agency has received more than 10,069 coronavirus-related complaints since March, but has issued just 24 citations.

“That’s ludicrous,” Harrison said. “It’s almost meaningless as any kind of enforcement or deterrent.”

Department of Labor spokesperson Sabin Sidney said that OSHA inspections have “helped to ensure more than 580,000 workers are protected.”

“OSHA continues to field and respond to complaints, and will take the steps needed to address unsafe workplaces, including enforcement action, as warranted,” he said.

Some state labor departments, including in Kentucky, are relying on their own public health rules instead of OSHA regulations to hold companies accountable for outbreaks in the workplace.

“Under OSHA rules, if we want to shut a company down that’s not protecting its employees you have to get a court order,” said Amy Cubbage, general counsel of the Kentucky Labor Cabinet, a state administrative body. “But under public health statutes we can shut down operations as we need to.”

State and local health departments follow CDC guidelines for tracking the pandemic. Many states have laws requiring doctors and laboratories to report cases, but the standardized form the CDC issued for doing so does not ask for the patient’s place of work or occupation unless the patient is a health care worker.

“The idea that occupational information is not being captured when data about Covid is being gathered in any source is absurd. It’s just foolish and a terrible missed opportunity,” said Gerstein, of Harvard and the Economic Policy Institute.

Many have begun to take action. States like Michigan and Washington are tracking information on patients’ occupation and place of work. The attorneys general in New York and Massachusetts have set up coronavirus worker safety hotlines. In July, Virginia became the first state to pass safety rules to protect workers from infection. Several others are working on similar legislation and more than a dozen states have broadened worker protections in response to Covid-19.

In early May, 13 attorneys general called on Amazon and Whole Foods to strengthen measures to protect the health and safety of workers during the pandemic and provide the states with, among other things, data about infections and deaths among their workers.

Amazon said it has responded to elected officials and held briefings with governors, state health departments and OSHA.

There’s no sign of the pace letting up. Amazon is hiring thousands more workers all over the country, and with the federal stimulus checks gone, the desperation for jobs with health benefits is unlikely to die down anytime soon.

“I feel like we’re just cattle to the slaughter,” said Angelia Mathlin, an employee at JAX1 in Jacksonville, Florida, whose spouse also works at Amazon.

William Stolz, a worker at Amazon’s MSP1 warehouse in Minnesota, said that employees had become “numb” to the notifications. He noted that the extra $2 per hour “hero pay” Amazon offered for working during the pandemic when it started in mid-March didn’t last long.

“We stopped being heroes in June,” Stoltz said.

CORRECTION (Sept. 30, 2020, 5:45 p.m. ET): A previous version of this article misspelled the first name of an Amazon employee in Jacksonville, Florida. She is Angelia Mathlin, not Anjlia.