With its graffiti and cracked exterior, the run-down warehouse sitting at 1305 31st Avenue in Oakland, California, did not look like a home at first glance.

Known as the Ghost Ship, it was an artists' collective. But, perhaps more importantly, it was a roof over the heads of a handful of residents who wanted an affordable place to call home in an area where the tech boom has priced most locals out of their long-time neighborhoods. No matter that the loft-like space was not zoned for residential living, and didn't have any sprinkler system.

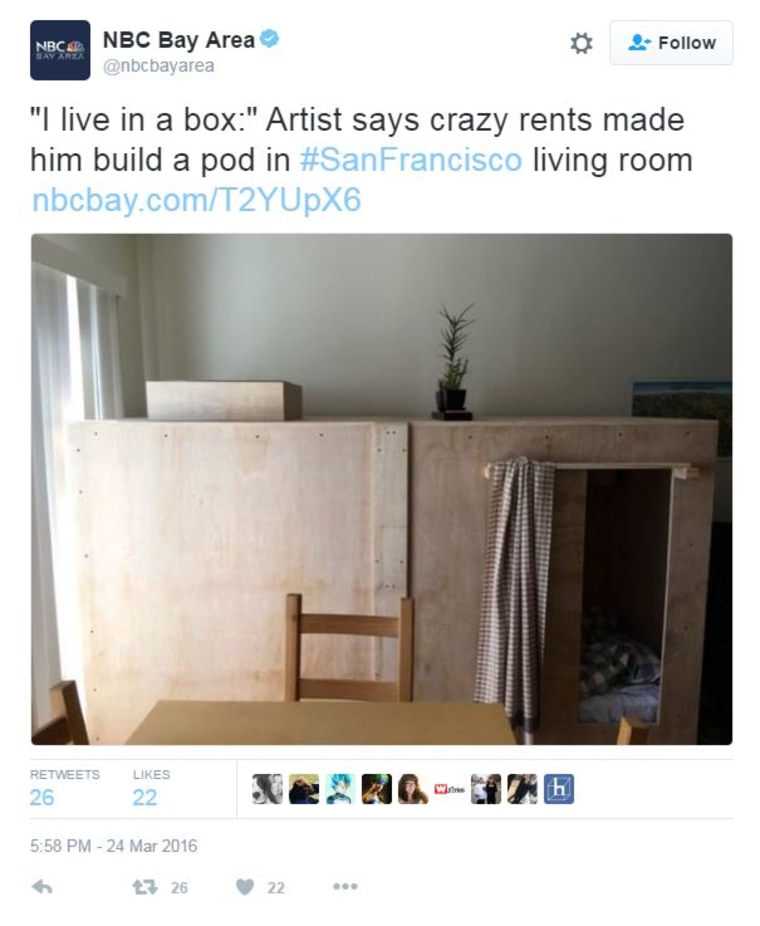

Friday’s fast-moving and fatal blaze that destroyed the building and killed close to 40 people has brought Silicon Valley’s housing crisis into the spotlight once again.

Sleeping in Shifts for a Lower Rent

The average rent for a one-bedroom apartment in Oakland was $2,210 in November 2016, according to Zumper's National Rent Report. Oakland has a median household income of $52,962, according to Census data.

"There are a lot of things people are doing to respond to the high housing cost, from overcrowding in single family dwellings or even lots of unrelated individuals in a one-bedroom apartment," Leslye Corsiglia, executive director of affordable housing advocacy group SV@Home, told NBC News. "I've even been in apartments where people slept in shifts."

In the case of the Ghost Ship, the building was last designated as a warehouse and did not have permits for residences or events, according to Darin Ranelletti, Oakland's Interim Planning and Building Director.

Carmen Brito, one of the people who lived at the warehouse, told TODAY that, "At some point, when you need somewhere to sleep at night, it doesn't matter whether you have a piece of paper telling you if that's OK or not."

"I think the thing you have to understand about the Bay Area is that it's incredibly difficult to find housing," she said. "If [you] go three blocks west of here, you can find plenty of people who couldn't find housing."

Dotcom Displacement

Silicon Valley has a shortage of around 25,000 homes, which means lower-income workers are completely priced out of the region. Many are forced to travel more than 50 miles to work and back each day. Even tech workers at industry giants must endure long commutes — an issue that companies such as Palantir, Salesforce, and Facebook have attempted to rectify by offering employees cash bonuses to move closer to campus, thereby relieving some of the strain on the inner cities.

"We haven't built enough housing in the region to keep up with population growth," said Stephen Levy, director and senior economist at the Center for Continuing Study of the California Economy.

"We're very short on supply, and what that has meant is the people with money have begun to bid up prices and rents on homes that used to be lived in by middle-class families," he told NBC News. "This leads to displacement for folks who see their rents increase."

Just last week, Elliot Schrage, Facebook's vice president of public policy and communications, announced the social media giant would invest $20 million to develop affordable housing and fund job training. But it's not simple philanthropy: As part of its gigantic campus expansion project, Facebook is legally required to give back to the community to regulate income inequality.

However, building new housing will require zoning approvals and various other red tape to cut through before the actual construction begins. As an immediate way to help, Schrage said $500,000 of that money would go toward an "assistance fund to provide legal support to tenants threatened with displacement from evictions, unsafe living conditions and other forms of landlord abuse."

In 2013, Google also stepped in to help with the housing crisis, committing $6 million to help build an affordable housing complex.

Corsiglia and Levy said they were happy to see tech companies doing their part to help with the problem. However, both said there's a greater issue at play that even Silicon Valley's deep pockets can't solve. There's an attitude of "not in my backyard" when it comes to building new, affordable units, they said.

"It is a modest drop in the bucket but it does not address the problem of people blocking housing projects," Levy said. "That will take zoning changes and political will."

With a limited amount of land to build on, Corsiglia said it's vital that future construction projects build for density, creating taller building with more units.

"In situations like Oakland, when you think of people who are struggling, it is a wide swath of people," she said. "It's artists, teachers, retail workers, and people we need in our community to keep our quality of life. It really is a wide variety of our population that is struggling."