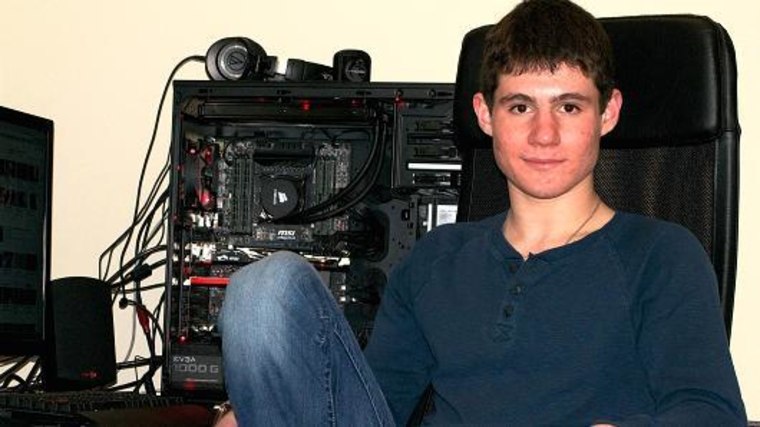

Shot through with intricate wires and crimson light, the space-age black box is where the magic happens. It's a homemade computer assembled by teenage tech wizard Andrew Bernstein.

"A couple of Korean off-brand screens and an Intel latest-generation 5820 6-core processor; it's water-cooled and over-clocked to 4.3 gigahertz and has an MSI gamer edition GTX 970 from Invidia. And it has 32 gigabytes of RAM."

Bernstein, 17, belongs to the first generation of humans born into a world dominated by digital technology. Unlike some older people, who may feel alienated in the rarefied atmosphere of high technology, this new generation feels completely at home in this world.

As jarring as this may be to anyone over 40, plenty of not-necessarily-young employers agree with this worldview, saying that workers of the pre-Internet generation often lack the quickly adaptable, independent thinking required to succeed in the fast-moving tech world.

It's an attitude echoed across Silicon Valley. Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg famously told a Stanford University audience that "young people are just smarter," in 2011— when he was all of 22.

"You need that brain plasticity in the world today. That's what makes these [young] people so good at what they do."

Bernstein works as a project manager at The Demski Group, a company that designs, manufactures and distributes specialized technology equipment. He draws a small salary ($400 a month) at the virtual company, which meets weekly on Facebook. The fact that he is only a junior in high school, Andrew says, does not matter in the least.

"I don't think my boss thinks much about my age, because I'm doing good work and getting things done," he said. In fact, the CEO of the Demski Group is in his early 20s and its marketing manager is a college student. According to Bernstein, younger workers are valuable to employers because "people who are younger can think outside the box."

Daniel Wendel, 32, a research associate and lead developer of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology's StarLogo Nova program, works with some of the best young tech minds in the country. Wendel believes that there are times when super-young inventors and programmers rightly belong at the apex of the modern tech workplace.

"You need that brain plasticity in the world today," insisted Wendel. "That's what makes these [young] people so good at what they do. Companies are having to be a little bit nimble and adapt quickly to support the hiring of these younger people."

Whether they should focus on education before entering the business world, however, is a "hotly debated topic," Wendel said.

"There's a whole movement in the tech industry about that. The founder of PayPal is paying people to dropout of college and work for his company," he said, referring to Peter Thiel. "These kids come into the workplace with the skills they need, just based on tinkering on their home computers."

Arjun Bhatnagar, one of Wendel's proteges, is the kind of young person he's referring to. By eighth grade, Arjun had already taught himself six programming languages (HTML, CSS, PHP, SQL, Java and Javascript.) One day, when he was fixing some computers at his father's office, he overheard some employees complaining about their inefficient internal communication system.

Read More: Workers at these 11 companies haul in $3.5 million each

"I said, 'Why don't you just build a social network?'" recalled Bhatnagar, now 18. "I knew how Facebook worked, and thought, 'How can I recreate that?' Facebook is not that complicated, really. I embedded software into their system and ended up building a private, full-fledged social network. My dad got a $2 million grant from the Federal Transportation Agency because of that."

By the time Bhatnagar was 16, he was teaching MIT undergraduate and graduate students coding and software installation. At 17, he helped design a customized prosthetic hand using 3-D printing technology. The following year, he invented a software platform called "Hey! HeadsUp" and is now the CEO of a company he co-founded with his 15-year-old brother, Abhijay.

"My dream job is to run a company building something really cool that helps a lot of people," Arjun Bhatnagar said.

TJ Evarts of Londonderry, New Hampshire, is also aiming to do that. At 14, he invented a potentially lifesaving product that he describes as "an intelligent steering wheel cover, a proactive solution to distracted driving." After appearing on the ABC reality show "Shark Tank," TJ got an offer of $100,000 and 30 percent of the company.

"We said yes on the show but the real negotiation happened afterwards," he recalled. "Ultimately, we decided to go in a different direction." Now gearing up for a June product launch, the 19-year-old CEO of Smartwheel USA, Inc., said being a teenage CEO can be rewarding—but it can be tough, too.

"Investors want to have faith that the entrepreneur knows what he's doing."

Read More: What happened to the American middle class?

"The advantages are obvious: You're not indoctrinated into any sort of a mindset about what can and can't be done. So you can do what everyone else is afraid to do," he said. "But getting monetary investment is tricky. Investors want to have faith that the entrepreneur knows what he's doing."

MIT's Wendel agrees.

"To some degree the future belongs to them. But I think experience counts for something," he said. "The experienced person thinking carefully about a problem brings wisdom and insight to it. There's a difference between being able to pick something up quickly and being really good at something. A toddler can pick up a language in less than a year, yet the number of novelists in the single digits is very small."