Judges in England were fooled into thinking the computer program they were conversing with was a human on Saturday — making it the first to pass the 65-year-old Turing Test.

"Eugene Goostman" is not a 13-year-old boy, but 33 percent of the people who partook in five minute keyboard conversations with the computer program at the Royal Society in London thought it was, according to The University of Reading, which organized the test.

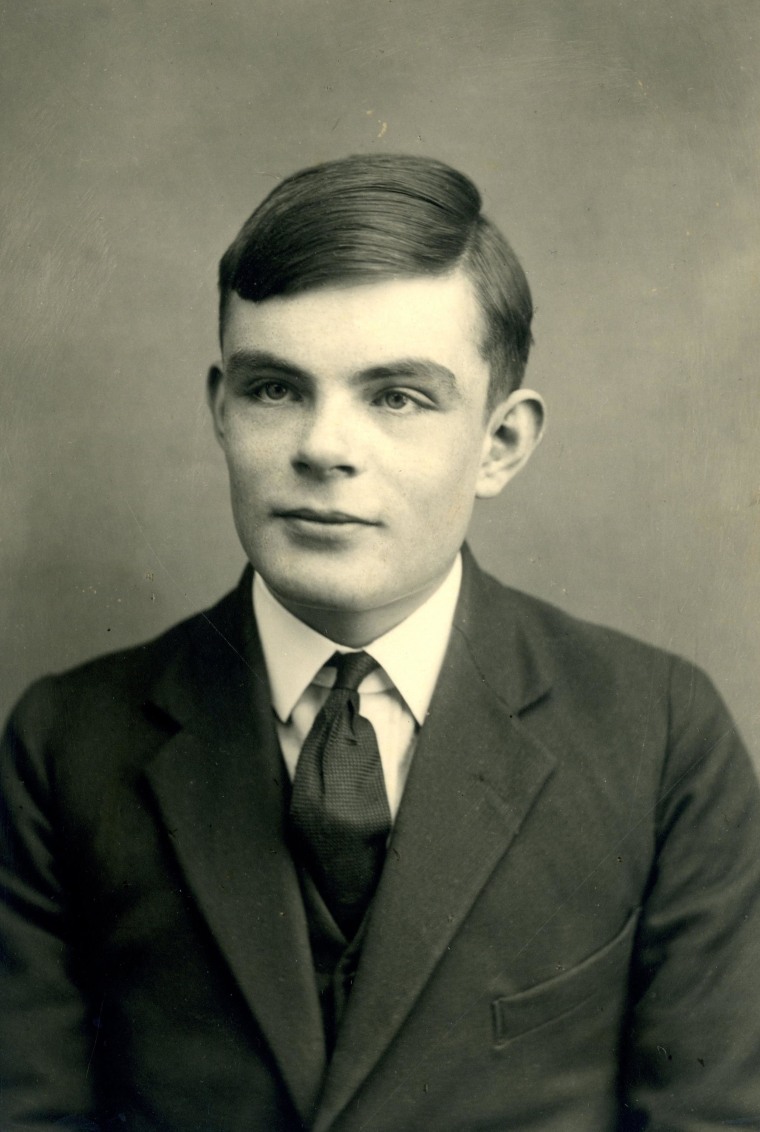

The Turing Test is based on “the father of modern computer science” Alan Turing’s question, “Can Machines Think?”

If a computer is mistaken for a human by more than 30 percent of judges, it passes the test, but no computer has accomplished the feat — until now.

“We didn't expect to break the barrier of the 30 percent, let alone the 33,” John Denning, the project’s director, told NBC News. “We came close before but we didn't really expect it to happen.”

“Eugene” was created in Saint Petersburg, Russia, by software development engineer Vladimir Veselov and software engineer Eugene Demchenko, according to the University of Reading. The computer program was tested along with four others during Saturday night’s event, but was the only one to thoroughly imitate a person.

“Our whole team is very excited with this result,” Veselov said. “Going forward we plan to make Eugene smarter and continue working on improving what we refer to as 'conversation logic.’”

Denning said part of “Eugene’s” success was that, although the test was done in English, the program’s conversation-style was written by non-native English speakers, who were forced to analyze the language and recognize its nuances.

Machines that can become as smart — or smarter — than humans raise concerns of dire economic consequences and diabolical robotic plots fit for science fiction movies.

But Kevin Warwick, a visiting professor at the University of Reading, says a computer that can think and act like a person will be an asset to battling cyber-crime. “Online, real-time communication of this type can influence an individual human in such a way that they are fooled into believing something is true ... when in fact it is not," he said.

Warwick pointed out that this weekend's test is also controversial because some claim it has been passed before, but the test did not pre-specify the topics of conversations and was independently verified. “We are therefore proud to declare that Alan Turing's test was passed for the first time on Saturday,” Warwick said.

“The event is particularly poignant as it took place on the 60th anniversary of Turing's death, nearly six months after he was given a posthumous royal pardon,” the university’s statement said.

Turing was instrumental in cracking Germany's Enigma code during World War II and came up with the concept of a “universal machine” that could act and think like a human.

He designed an electromechanical device known as the "bombe,” which allowed a team code-named “Ultra” to decode intercepted German messages. British Prime Minister Winston Churchill credited "Ultra" with winning the war.

Turing wasn’t lauded though. Instead, he was barred from working with the British government and charged as a criminal with “gross indecency” because he was gay.

The trailblazer killed himself with a poisoned apple at 41-years-old, tormented by the law and impossibility of exoneration.

Queen Elizabeth II granted a “mercy pardon” to Turing in 2013, but he never lived to see anything close to the seemingly-unrealistic machine he had dreamed up decades before its creation.

“It is difficult to conceive that [Turing] could possibly have imagined what computers of today, and the networking that links them, would be like," Professor Warwick said.