The forgetfulness that comes with age may be reversible, researchers reported on Wednesday. They found the brain cells involved in normal, age-related memory loss don’t die. They’re just turned down.

The researchers found a single gene associated with the normal but infuriating loss of memory that torments most people as they age – and found it might be possible to restore its function. If a drug is found to do that, it would for all intents and purposes be a memory pill.

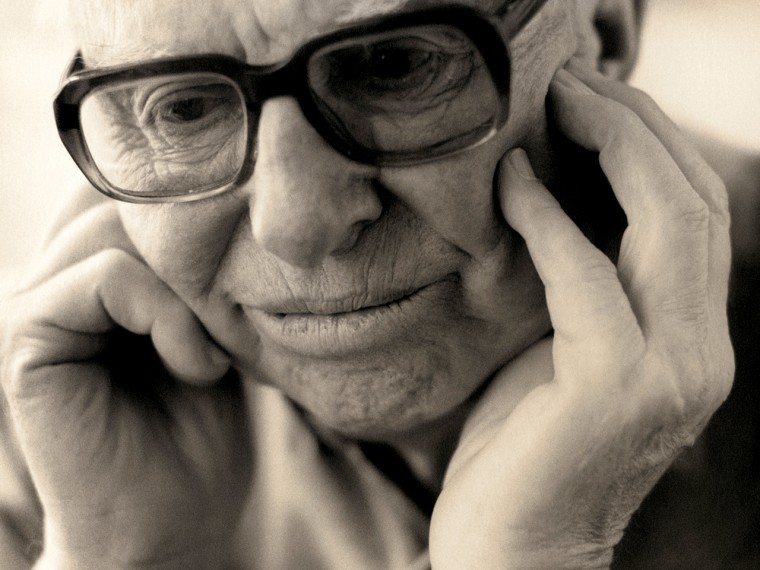

While many people are working on a cure for Alzheimer’s disease, this study, led by Dr. Eric Kandel of Columbia University in New York, points to a way to help healthy people keep their minds sharp.

“Our study provides compelling evidence that age-related memory loss is a syndrome in its own right, apart from Alzheimer's,” Kandel said in a statement.

“In addition to the implications for the study, diagnosis, and treatment of memory disorders, these results have public health consequences.”

Kandel, who shared a Nobel Prize in 2000 for his work on memory, says his team is already looking for drugs that might turn this gene back on.

They started by looking at the brains of eight people aged 33 to 88, who died with no evidence of brain disease. They took samples from the dentate gyrus, a part of the brain that’s affected by aging.

Just about every cell in the body carries two copies of each gene, but different genes are turned up or down in different types of cells. This is called gene expression. Kandel’s team looked to see which genes were expressed more or less, depending on age.

A gene called RbAp48 was clearly more active in the brains of the younger people than the older people, the team reports in the journal Science Translational Medicine. It didn’t seem to change in a different part of the brain.

The team double-checked in a second batch of 10 human brains from people aged 41 to 89. Again, the older they were, the less RbAp48 they found in the dentate gyrus.

Checks in mice showed the same pattern. And while mice don’t get Alzheimer’s the way people do, they do lose memory as they get older.

They made genetically engineered mice, in which they could control how active RbAp48 was. When RbAp48 was cranked up to normal levels, the mice were able to remember how to navigate a maze like normal, young mice.

The mice also passed another memory test better when RbAp48 was turned on normally. At levels seen in aged mice, they sometimes forgot objects they had seen the day before. Mice are curious and sniff new objects – mice with cranked-down RbAp48 ran over to objects they had seen before as if they were new.

Tests with normal mice showed that old mice acted just like mice whose RbAp48 was turned down.

The final test was to see if forgetful mice could be “cured” by turning RbAp48 back on. Using gene therapy, the team restored the gene in old mice. “It no longer has memory loss,” Kandel said.

“We were astonished that not only did this improve the mice's performance on the memory tests, but their performance was comparable to that of young mice," said Elias Pavlopoulos, who worked on the study.

Gene therapy doesn’t work well in people, yet, and it’s not practical on a large scale. But Kandel thinks it’s possible to use drugs to turn it back on in older people. “We certainly will try,” he said in a telephone interview.

“(This gene) is a likely target. There may very well be other players.”

The other question is why the gene gets turned down as people, and mice, get older. “We don’t know,” says Kandel. “Is it a dietary factor? Is it an environmental factor? There are lots of processes in your body that age.”

But the brain cells themselves aren’t dead – unlike in Alzheimer’s. And Kandel says much work has been done on the pathway that controls this gene. There might be drugs that can interrupt the process that turns the gene down, he said.

"Now we have a good target, and with the mouse we've developed, we have a way to screen therapies that might be effective, be they pharmaceuticals, nutraceuticals, or physical and cognitive exercises," said Dr. Scott Small, director of Columbia's Alzheimer's research center, who worked on the study.