Statistics and data mining aren't typically associated with literary analysis, but new research suggests that such objective methods may be both powerful and relevant. Not everyone is impressed, including scholars who don't care to be replaced by supercomputers.

Matthew Jockers, assistant professor of English at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, has devised a method of comparing thousands of books to one another in order to find systems of influence, schools of thought and other groupings that may not be obvious to literary theorists. He calls it macroanalysis.

"We need to go beyond our traditional practice of close reading and go out to a different scale," Jockers told NBC News. "The traditional practice of close reading allows us to look at the bark on the trees, while the macroanalytic allows us to see the whole forest." Modern programming and data mining tools, combined with widely available digital texts, make this approach possible.

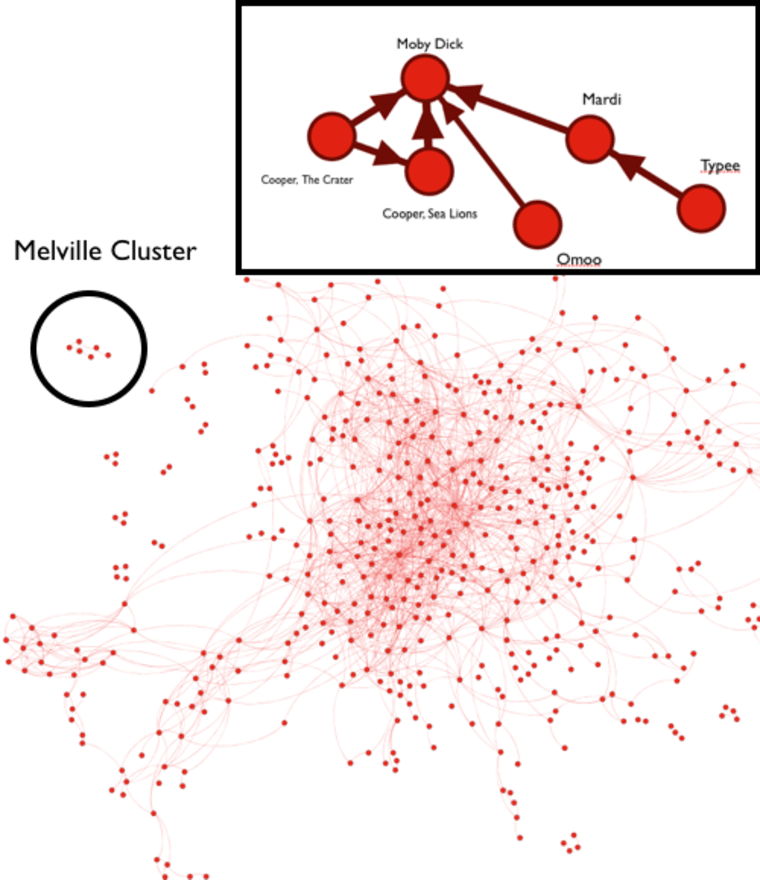

His system processed thousands of digital books from the 19th- and late 18th centuries — a period chosen because the works are free, plentiful and subject to a wealth of theory already. The books are examined on dozens of measures, from word choice to punctuation to overarching theme. The end result is a unique "book signal" that allows it to be compared to other books and eventually plotted in a sort of similarity space, where closely related books are near one another, and differing books are distant.

It makes for a striking graphical representation:

But it's not just about making a pretty picture. By looking at how books are distributed based on certain metrics, there are many trends and facts to be gleaned.

Some aren't particularly surprising, like the fact that Jane Austen and Sir Walter Scott are rated very highly for originality and influence. But less obvious things emerge as well. Jockers' systematic approach helped illuminate the reasons for a decline in the visibility of Irish-American authors early in the 20th century, closing a gap in knowledge that had been speculated about for years (for those interested, it turns out they temporarily changed the seat of their literary voice to more rural, western climes, away from the urban, eastern areas with which they are traditionally associated).

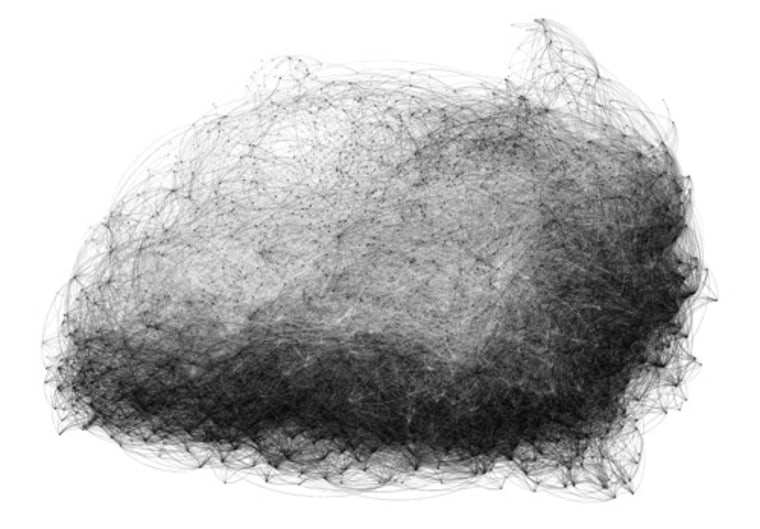

And other powerful patterns emerge: female authors, for instance, were grouped closely at one end of the book space, even though their gender was not part of how they were placed. You can see it in the rendering below; the darker-colored areas represent groups of women authors. So female authorship is indeed detectable, not just by well-honed human intuition but by objective measures.

Other themes and measures can also be shown to group or separate themselves, so certain styles, eras and so on can be described not just anecdotally, but systematically, using nothing but the text as data.

Naturally, there are objections. Jockers is aware of them: "One of the criticisms is that it succeeds in refinding what we already knew." In other words, why bother proving statistically what we already know from close reading?

But other sciences have different methods for obtaining the same result, such as measuring the diameter of the Earth or the pH of an acid. Why shouldn't literary theory have the same thing? "These are not competing methodologies, but complementary ones," explained Jockers. For instance, while the approach showed definite clustering of female authors, an interesting finding, this level of organization fails to show that many of the best-known works by women were in fact not in that group. Pointing that out and examining why it is so are jobs best done by humans. So as the high-level approach presents a new perspective, it may prompt new work in more traditional fields as well.

Macroanalysis could be applied to modern literature as well, and of course other languages, but it's not just a box where you put in books and out comes theory. It takes critical thought to dissect the results and apply them to existing thought. But it's not hard to imagine new books coming out with a computer-determined thematic and stylistic analysis printed on the dust cover.

The work was presented as a paper and talk in Hamburg, but in its final form it will be the final chapter of a book Jockers is working on called "Macroanalysis: Digital Methods and Literary History," due to be published soon by University of Illinois Press. He's trying not to make it too dry: "I want this to appeal to my literary colleagues who aren't programmers. It's not laden with theoretical jargon." Curious statisticians and literary theorists alike should find it an interesting read.

Devin Coldewey is a contributing writer for NBC News Digital. His personal website is coldewey.cc.