Google has awarded a $5 million grant to the World Wildlife Fund to use and adapt new technologies to combat animal poaching around the world. The group has grand plans for the money, which will be used for everything from camera-equipped drones to next-generation animal tags that send text messages with critical information to rangers.

"We needed to find other ways where we could detect and deter poachers," Crawford Allan, head of wildlife trade organization TRAFFIC North America and one of the WWF's on-call experts, told NBC News. "It's been fairly rudimentary in places where there are very precious species to protect."

Poacher operations have grown in scale and sophistication, despite efforts to curb them. Rhinos used to be poached at a rate of 15 or 20 per year in Africa — but now, because of high demand for rhino horn coming primarily from Asia, over 600 have been killed this year alone. Statistics for elephants and tigers are equally disturbing.

Enter Google, which awarded the Washington, D.C.-based WWF the grant as part of Google's Global Impact Awards: a larger, $23 million effort to fund tech uptake in areas like preservation and humanitarian endeavors. Allan describes the grant as an incredible opportunity.

"We could have just gone on business as usual, making small steps," he said. "But now that we have a major partner in Google, we can finally take some big steps."

Part of the money has to go to such logistical concerns as updating laptops, buying gas for patrols, and making sure people on the ground are safe and well-supplied. But such a large grant also means the WWF can finally deploy technologies it's been waiting on for years.

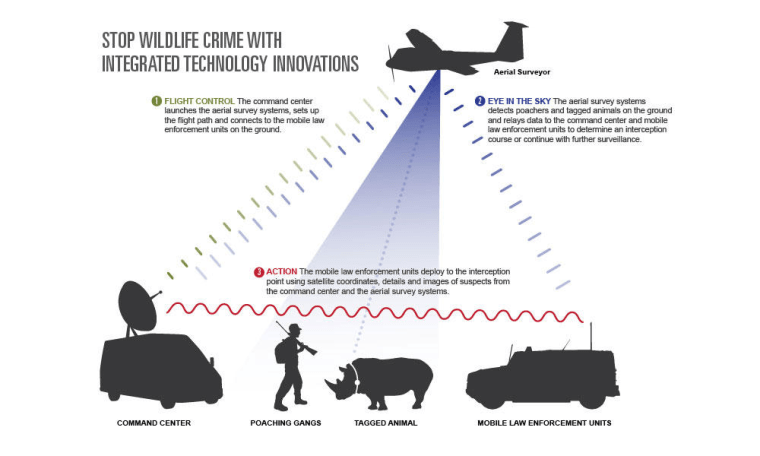

For instance: Drones. Not fully autonomous ones, but human-piloted platforms that can relay information like acoustic signals and infrared imaging in real time to their operators and patrols on the ground.

"With the aerial vehicles, we have not selected any particular system, and we may be looking to tailor one to our needs," Allan said. "But we're not going to be using a $200 hobby-shop device. We're probably looking in the tens thousands of dollars range."

Such a platform would need to strike a balance between cost, capacity, noise, portability and many other factors. The WWF is doing initial aerial platform testing at sites in Namibia and Nepal, and is hoping to partner with interested local governments.

Another big advance the WWF is excited about is a new system of animal tags. Existing ones are clunky, use antiquated software, and have a fairly limited battery life.

A new type of tag is in the works that would work on a similar system to a GSM cellphone, and would not only be lighter and stronger, but would last longer (up to two years) and be able to collect and transmit far more data.

Animals' tags could text park rangers with the animals' location and status, or retain and transmit other rich data. And they should only cost around $250 each — peanuts compared with the tags the WWF uses now, each which can cost as much as $4,500, with extra fees for satellite coverage.

But perhaps what the organization is looking forward to the most is a new, overarching system for integrating all the data created by satellites, aerial vehicles, patrols on the ground and government reports. The methods for handling all this data aren't nearly good enough right now, said Allan.

He also said that authorities aren't always willing to put this kind of infrastructure in place on their own, whether because of cost or corruption. The poaching business is very lucrative and officials in developing countries can be convinced to turn a blind eye for a price.

With the integrated system and better data for everyone involved, the WWF can work with international police and other non-governmental organizations to track poached animals and parts using DNA analysis, law enforcement records and other resources.

The process is just beginning. Allan cautions that while the grant is going to make many things possible, it's not going to revolutionize the anti-poaching world overnight. The WWF expects the testing and rollout of the new technologies to take a couple years at least.

In the meantime, Allan and others hope that just the idea of such powerful tools being put into the field will act as a deterrent.

Poachers may be confident when all they have to worry about is rangers with radios and jeeps. But when there's an army of networked drones, smart sensors and high-tech surveillance watching every animal for miles, they may think twice before sneaking onto the Savannah.

Devin Coldewey is a contributing writer for NBC News Digital. His personal website is coldewey.cc.