At the same time that our country is dealing with the ravages of a highly contagious pandemic, it is also facing a population — and politicians — increasingly distrustful of the integrity of the voting process. Those two phenomena put our democracy on a treacherous path as we barrel towards Nov. 3.

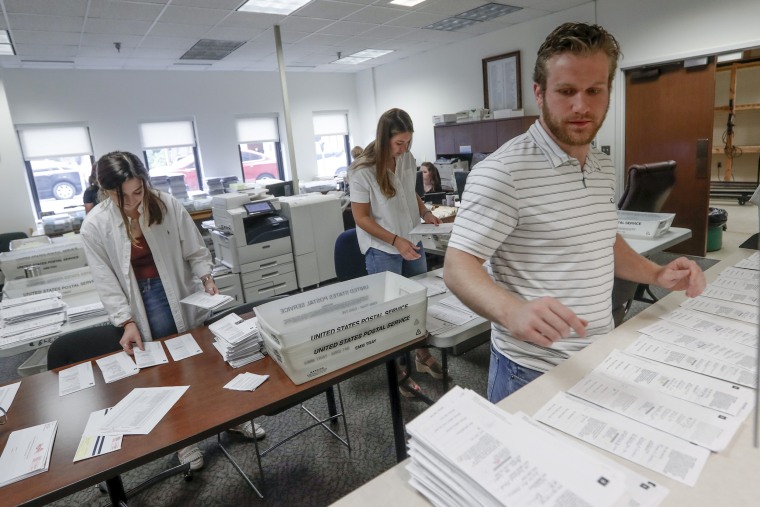

For a small dress rehearsal of what our increasing use of mail-in ballots and other socially distant forms of voting means in practical terms, take a look at what happened in New York and Kentucky this week. Though thousands were able to exercise their democratic rights from the safety of their living room — crucial to safeguarding citizens’ health as well as their rights — the tabulation systems were swamped by the flood of mailed-in votes on Tuesday night, meaning results still haven’t been determined.

Some 21 percent of the population — Democrats and Republicans nearly equally — think that violence could be justified as a response to a politician of an opposing party winning in 2020.

And these were for relatively low-turnout primaries. Without a major investment in ramped-up electoral administration, the system will be totally overwhelmed come November, when voter turnout is expected to be much higher. A delayed count is just the spark irresponsible political leaders stoking the flames of electoral doubt could fan into a dangerous fire of delegitimization.

On Thursday, Attorney General Bill Barr dumped more fuel on the baseless claim — promoted by his boss, President Donald Trump — that mailed ballots will lead to fraud, despite zero evidence that they have in the past. In Michigan, Trump supporters have been burning their absentee ballot applications in protest. It is not far-fetched to think that this type of outrageous political theater can morph into a real challenge to the calm transition of power that is the bedrock of American democracy.

That danger will become even greater over the weeks of counting and waiting if it emerges — as is likely — that the post-Election Day tallies go decisively in favor of Democrats. This “blue shift” is to be expected. Historically, late-counted votes have tilted Democratic, and this is especially probable in 2020 because Republican voters will almost certainly be more likely to vote in person after months of hearing their president tell them that mailed ballots could be stolen, and that they don’t need to worry about staying socially distant. (Already, Democrats are requesting mailed ballots at much higher rates than Republicans.)

If Trump wins, Democrats will have plenty of cause to doubt the results, too. Widespread concerns over systematic voter suppression and foreign interference are common among Democrats, and these violations are both more likely and more believable if election administrators are overwhelmed.

Indeed, having the outcome of national elections unknown for long stretches would be undesirable in any era, but in this particular era, it is especially challenging. An NPR poll earlier this year found that only 62% of Americans across the political spectrum think U.S. elections are fair.

More troubling, some 21 percent of the population — Democrats and Republicans nearly equally — think that violence could be justified as a response to a politician of an opposing party winning in 2020, according to a recent Voter Study Group analysis by Nathan P. Kalmoeand Lilliana Mason.

We are facing a predictable disaster. And if we’ve learned anything from the COVID-19 pandemic, preparing for a predictable disaster is better than not preparing for it. So, how can we prepare to prevent this potential election month legitimacy crisis?

First, and most important, we all need to be mentally prepared for the very real possibility that it may take weeks to deliver a definitive result — and understand that these delays do not reflect fraud. In fact, they will be necessary to prevent fraud.

Counting ballots accurately and fairly, ensuring that signatures match and employing other verification measures requires time. It’s much better that election administrators do what they need to to ensure security than rush through processing the ballots. Both the press and politicians need to accept and expect this, and communicate the message to everyone: This may take some time. Be patient. This is an exceptional circumstance, but not a corrupt one.

Second, while Trump and his most loyal acolytes may be a lost cause at this point, it’s still crucial for other political leaders — especially Republicans — to remind voters that voting by mail is in fact very safe and secure, and fraud is rare. In America, death by lawnmower is more common (about 75 unfortunate souls a year are lost to machines that cut grass) than voter fraud. According to the conservative Heritage Foundation, there have been only 1,200 cases of voter fraud of any kind among millions of ballots cast over the past two decades — about 60 cases per year. Trump and Barr have themselves both voted by mail, as have at least 14 other administration officials.

Mailed ballots have multiple safeguards and are extremely common; in 2016, 22 percent of Americans used them. And they have betrayed no partisan favoritism in previous elections. Instead, they’ve delivered a small boost in general election turnout for both major parties.

Of course, if Democrats use mail-in ballots more than Republicans this year because of Trump’s attacks on them and his downplaying of the dangers of exposure to coronavirus, that advantage could change — with potentially destructive consequences for its cross-partisan legitimacy.

Third, election administrators need more resources. House Democrats proposed $3.6 billion for election infrastructure in the May coronavirus stimulus bill. The final bill had a mere $400 million, far short of what experts say is needed. Printing and mailing ballots costs money. Hiring people to count mailed ballots costs money. The more resources election administrators have to process ballots quickly, the less likely we are to collectively suffer through the purgatory of extended uncertainty, that breeding ground of distrust.

Fourth, we need to ensure that in-person as well as mail-in voting is safe and accessible. This also requires resources. Interminable lines like those we saw in Wisconsin and Georgia primaries are unacceptable. The more polling places that are open, and the more people staffing those polling places, the faster and more safely voters who need to vote in person will be able to do so.

Without a major investment in ramped-up electoral administration, the system will be totally overwhelmed come November.

Here’s something you can do if you are young and healthy and want to help secure our democratic process: Volunteer to be a poll worker. Volunteer poll workers historically tend to be older, and volunteering in 2020 will put their health unnecessarily at risk.

Holding an election during a pandemic would be an immense challenge under any political circumstances. But with a president dead-set on delegitimizing the one method of voting necessary to save lives and ensure the safety of elections — mailed ballots — the degree of difficulty at present is staggering. We all need to prepare ourselves for the possibility of a close election in November that goes into ballot-counting and litigation overtime. And then we need to do everything we can between now and then to prevent it from breaking our democracy.