Economy cabins already often feel like cattle cars, yet airlines are thinking thin to fatten the bottom line, relying on new seat designs and cabin layouts that may have fliers feeling more cramped than ever.

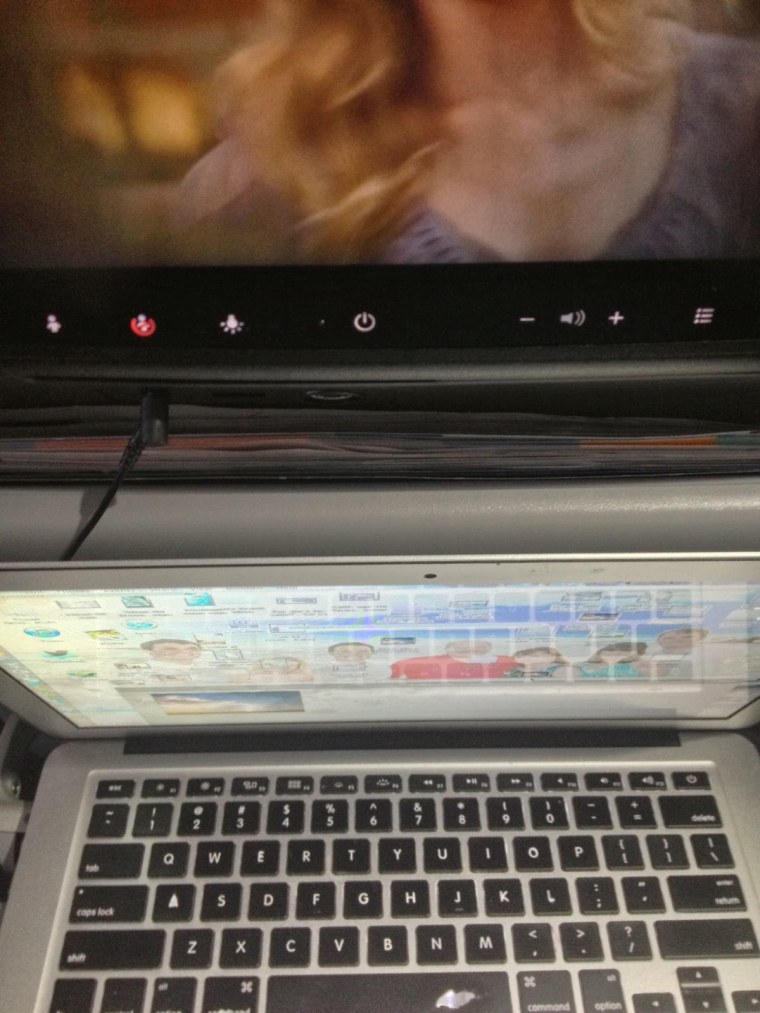

Mike Smith, a Wichita-based meteorologist, had his own too-close-for-comfort experience when he tried to use his computer during a recent flight from Dallas to Wichita on an Airbus A319 operated by American Airlines.

“I have a MacBook Air and I couldn’t open it to the point where I could actually use it,” said Smith, vice president for AccuWeather Enterprise Solutions. “The seating was more cramped than any regional jet I’ve ever experienced.”

Such experiences may become increasingly common as airlines take advantage of new seat designs that allow them to squeeze an extra row of seats into economy cabins and, in some cases, an extra seat into existing rows.

“The airlines are trying to maximize revenue by adding more seats without sacrificing space,” said Ranga Natarajan, senior product manager for SeatGuru.com. “Some have done a good job; in others, space is limited so people are feeling cramped.”

Many of those new seats are so-called slimline models that are less bulky than their predecessors. Utilizing lighter materials, thinner cushions and ergonomic designs, the seats take up less space, allowing many carriers to add an extra row to their cabins.

United, for example, has added six seats to its Airbus A319s and A320s; Southwest has added six seats to its Boeing 737s, and Alaska has added six to nine seats to its Boeing 737-800s and 737-900s, respectively.

From a revenue perspective, the new seats are clearly a winner. Adding six seats to an economy cabin that previously held around 140 seats can boost revenue by 4 percent or more. And lighter seats translate into fuel savings. Southwest, for example, expects the new seats to trim $10 million a year off its fuel bill.

From a passenger perspective, the reviews are more mixed. In many cases, the new seats’ thinner profile and other design changes have allowed airlines to add seats without reducing seat pitch, which serves as a rough approximation of legroom. And while Smith, at 5-foot-9½, found his seat exceedingly cramped, Natarajan, at 5-foot-10, considered his seat on a recent Southwest flight “very comfortable.”

For their part, the airlines maintain that many fliers won’t notice the difference at all. And while that may be true, it also overlooks two other factors that currently define the flying experience.

Cramped or comfortable, more seats per plane means more people hoping to use already stuffed overhead bins, more people in the aisles and more opportunities to get jostled, bumped and overly familiar with your fellow passengers.

Secondly, legroom is only half (or less) the story on seat space. Perhaps the bigger issue is width, which impacts both individual travelers and those around them.

“When designers think seat, they think butt, but the widest part of the body is the shoulders,” said Kathleen Robinette, head of the Design, Housing and Merchandising department at Oklahoma State University and a 30-year veteran of the design-focused Air Force Research Lab.

“At least 20 percent of the population is probably wider than the seats [as currently designed], and if one out of five is too big for their seat, that affects the people next to them,” said Robinette. “They’re almost guaranteeing that the majority of people on the plane are going to be uncomfortable.”

And more people are likely to face that unpleasant situation. As recently reported in The Wall Street Journal, several airlines are adding an extra seat in each row of their widebody jets. They’re doing so by reducing seat width from the 18 or more inches common on long-haul and international flights to the 17 inches typically found on shorter, domestic routes.

While such plans are strictly the province of individual carriers, the issue has also become a contentious one among airline manufacturers. Earlier this week, Airbus proposed a minimum industry standard of 18 inches for long-haul flights, which it’s also touting in a new “It’s the seat” marketing campaign.

The move, while designed to appeal to travelers, is also a dig at Boeing, which has delivered an increasing number of planes with 17-inch seats, allowing for one extra seat per row, at the behest of its airline customers.

“It’s one thing if a plane is only half or two-thirds full but when it’s a full flight, it’s not much fun at all,” said Douglas Kidd, executive director of the National Association of Airline Passengers. “When they serve meals, you have to eat like a praying mantis and crossing your arms for the entire flight is not an option.”

“Most airline seats are already too narrow,” said Robinette. “If they get any narrower, it’s going to be a disaster.”

Rob Lovitt is a longtime travel writer who still believes the journey is as important as the destination. Follow him on Twitter.