With the attempt to unionize football players at Northwestern University, and antitrust lawsuits being fought against the governing board of college athletics—the NCAA—experts say the day when student athletes are classified as workers and get paid may not be far off.

But how much money could a player get on the open market? According to one report, it would likely mean salaries in the hundreds of thousands of dollars, if not more.

"The bidding war for athletes would likely be in the millions," said Ellen Staurowsky, a professor of sports management at Drexel University and co-author of the report.

"However, I think it all depends on whether or not a players' association ends up representing the teams and players," Staurowsky told CNBC by phone. "The salaries could be effectively bargained to have some sort of minimum guaranteed salary for all."

"The bidding war for athletes would likely be in the millions."

The March survey, from the National College Players Association and Drexel University, said that the projected fair market value of the average college football player is $178,000 per year from 2011 to 2015, while the projected market value for the average college basketball player for the same time is $375,000.

The report also said that football players with the top 10 highest estimated fair market values, like Texas A&M quarterback Johnny Manziel, might be worth as much as $547,000, during the year 2011 to 2012.

Basketball players with the top 10 highest estimated fair market values, such as Kansas Jayhawk forward Andrew Wiggins, for instance, might be worth more than $1.6 million for the same year.

The report states that the fair market value was calculated using the revenue sharing percentages defined in the NFL and NBA collective bargaining agreements and team revenues as reported by each school to the federal government. The NCPA is headed by Romagi Huma, who is leading the effort to unionize the Northwestern football players.

Hurdles to a payday

Getting to a college athletes' payday, while seemingly inevitable to some, won't be easy. There are numerous hurdles, such as legal challenges to the Northwestern union effort. The NCAA has vowed to fight any effort to change the status of college athletes to employees, and allow any kind of direct salary—as has Northwestern.

Northwestern's football team is expected to vote on whether to unionize on April 25.

And critics claim the likely bidding war for high school athletes would force many schools to throw in the towel when it comes to fielding sports teams—saying the cost of paying would be too much. And there's always the argument that athletes do get paid, through scholarships.

Advocates for paydays see it differently.

"People are missing the point on all this," said David Hollander, professor of hospitality, tourism and sports management at New York University. "It's not whether we should pay college athletes but that if you are an employee and your job is to play sports, than you should get paid."

Hollander also said that the U.S. is the only country that uses college athletes as a way to develop players for the professional leagues and that having player development outside of college avoids the "hypocrisy of student-athletes that are really unpaid players."

As for a bidding war over salaries, a war is already in place, said Drexel University's Staurowsky.

"It's not whether we should pay college athletes but that if you are an employee and your job is to play sports, than you should get paid."

"Colleges use high-end facilities, training rooms and other means to attract high school players so it's really nothing new to make a bid for a player," she said.

Staurowsky also said that athletic scholarships don't nearly cover all the financial needs of an athlete and can be terminated at any time by a coach or ended with an injury.

Potential for corruption

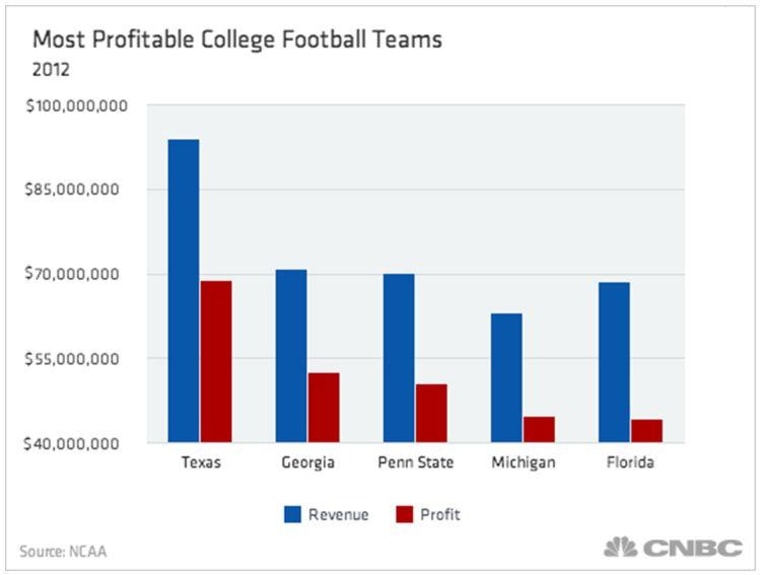

The revenue from college sports is huge—some $10.6 billion was generated from college athletics in 2012, according to the NCAA.. The average division one school got $15.8 million of that for football alone. Massive TV deals to broadcast college football and basketball games on ESPN and local networks are reaching record levels—with the money being shared among participating universities.

Salaries for college coaches are also rising, some say on the backs of the players. For his role in guiding the Wichita Shockers to the college basketball's Final Four in 2013, coach Gregg Marshall reportedly earned $545,000 in bonuses. That came in addition to his $1.6 million salary for 2013-14, making his total compensation $2.145 million.

Alabama football coach Nick Saban garners a total package of $5,545,852 a year, making him the highest paid coach in college football.

But fears remain over turning college athletes into employees. Would a company like Nike or Adidas dangle millions in front of a high school senior to wear their sneakers? Will agents throw hundreds of thousands of dollars in front of 17-year-old kids in order to represent them?

"There's always the potential for corruption when it comes to money," said Drexel's Staurowsky.

"However, the corruption in college sports is here already. And this is not just about the money," she said. "There's health and safety issues for players. If done right, paying college players can work."