With Major League Baseball’s post-season now underway, it’s safe to say that plenty of dirt will be dished as the Royals, Orioles, Giants and Cardinals vie for spots in the World Series. And while it’s less likely to be talked about, there will also be mud — that is, Lena Blackburne Rubbing Mud, which will play an unsung but essential role from first game to last.

A tradition for more than 75 years, the mud is the solution to a longtime problem. Fresh out of the box, baseballs feature a glossy surface that makes it hard for pitchers to get a good grip, a dangerous situation for batters facing 95-mph fastballs. That’s why MLB Rule 3.01c states that all balls must be “properly rubbed so that the gloss is removed.” Mud scuffs them just enough to do the trick.

But not just any mud. Since 1938, the mud of choice — today, it’s the only mud used by every team in the major and minor leagues and most college associations — comes from a secret spot on a tributary of the Delaware River in southern New Jersey.

“There’s something special about it,” said Jim Bintliff, the 57-year-old owner of Lena Blackburne Rubbing Mud. “The minerals make it like a fine-grit sandpaper. It buffs the gloss off the ball without damaging the leather.”

It was discovered by the original Lena Blackburne, then a manager for the Philadelphia Athletics, after other methods — tobacco juice, shoe polish, infield dirt — proved ineffective. Delaware River mud, on the other hand, seemed to work just fine, and before long, he had a small business shipping jars of his “magic mud” to teams across the country.

Today, Bintliff, grandson to Blackburne’s partner, harvests the mud from July to October, waiting until most people have gone to work before heading for his secret spot. Gathering 1,000-1,500 pounds of mud per season, he hauls it home, cleans it and stores it over the winter before selling it the next spring.

Professional teams typically buy it by the 32-ounce tub ($75, up from $50 in 2008), but you can also buy a “personal size” jar for $24. “I’m not getting rich at it,” said Bintliff, declining to reveal the company’s annual sales.

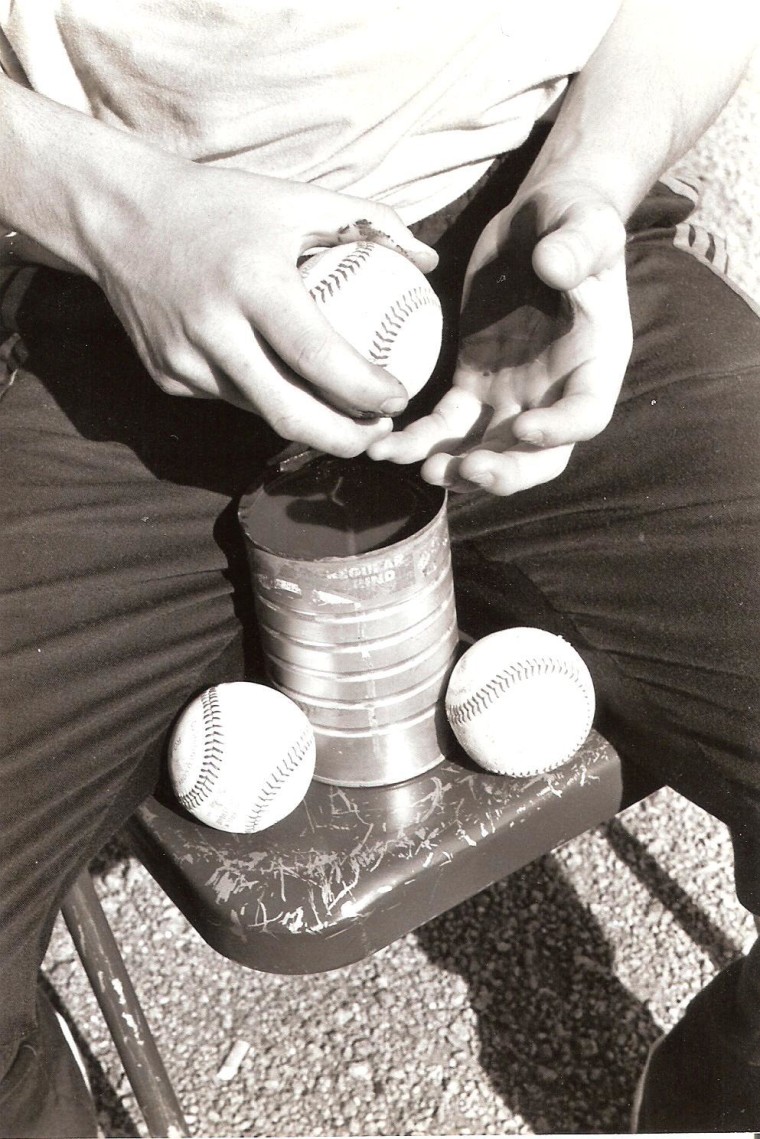

Despite the mud’s pivotal role, the actual rubbing is a fairly straightforward affair — a dab of mud, a little water, a few spins between the hands. “Some guys use saliva, some just use water; one guy used to use a spray bottle,” said former MLB ump Gary Darling. “You don’t want them too dark or too light.”

“It takes about five minutes per dozen,” said Dean Lewis, who handles ball-rubbing duties as a clubhouse attendant for the Boston Red Sox. On game days, he rubs six to eight dozen before the game and more during the game as the situation warrants.

That’s a lot of balls, especially when you extrapolate the numbers across the entire league and regular season. With 30 teams each playing 162 games, that works out to 2,430 matchups; if Lewis’ counterparts also rub 72 to 96 balls per game, that means that somewhere between 175,000 and 233,000 balls get the treatment. The preseason, playoff series and other leagues only add to the numbers.

All of which keeps Jim Bintliff busy. As he says, he’s not getting rich but there’s still a payoff for spending his days up to his ankles in Delaware River muck.

“It’s such a part of the game,” he said. “Every ball, every game, every day. From the first day of spring training to the last out of the World Series, we’re there.”