July was officially the hottest month on record, and in the scorching sun, UPS workers have convulsed, fainted and landed in the emergency room with heat-induced kidney failure, interviews and medical records show.

Sixteen employees of the delivery company told NBC News they have suffered heat illnesses so far this summer, highlighting the continued hazards UPS workers face as workloads ramp up in record temperatures.

Last month, an NBC News investigation revealed that more than 100 UPS employees were hospitalized for serious heat-related injuries between 2015 and 2018, more than any other company in the country except the U.S. Postal Service. UPS, which has almost 400,000 employees, 74,000 of them delivery drivers, does not air condition most of its warehouses or its brown delivery trucks, whose cargo areas can reach 150 degrees, drivers said.

Since the story aired, NBC News has spoken with UPS employees around the country who said this summer has brought heavy loads, long days and mounting pressure to deliver in record heat.

"This is supposed to be our slowest time of the year and we've been working like it's peak season," said Jamie Scarborough, a loader at the sprawling UPS air hub in Louisville, Kentucky.

Workers in Arizona, Louisiana, Virginia, Florida, Texas, Wisconsin, Kentucky and Georgia said UPS is failing to follow its own heat protocol.

Managers push employees to keep working even when they're sick and discourage them from reporting illnesses, they said. When employees insist on treatment, they said they are often taken to urgent care centers that cannot administer IVs, delaying crucial care.

"This is just sickening," said a union steward in Arizona, who has seen three drivers suffer heat illnesses since late July. "They preach about safety and heat related issues," he said. But when workers report that they are ill, he said, managers "get upset or just don't follow the safety protocol."

Workloads are not likely to ease up. Last week, FedEx severed ties with Amazon. Some of the 200,000 packages FedEx delivered daily will likely shift to UPS, which just announced it will start delivering seven days a week in 2020. UPS currently handles about a quarter of Amazon's volume, according to ShipMatrix, a consulting group.

Steve Gaut, vice president of public relations at UPS, said the amount of freight has increased this summer, but the workload has not. He also said he "cannot corroborate the existence of 'record heat'" this summer, "as this is dependent on the geographic location of the employee and the period in question."

UPS has measures in place to help protect workers, encouraging them to hydrate, take breaks and report heat illnesses to supervisors. Managers are supposed to ensure employees receive medical attention when necessary.

Some managers do. But workers said corporate pressure to get packages out and keep injury numbers low leads others to hide illnesses by sending employees home rather than encouraging them to report injuries and seek medical care.

The true scope of heat injuries is "staggering," said Chris, a driver in Florida who asked to be identified only by his first name. "The problem is so many haven't been reported, so there's no paper trail."

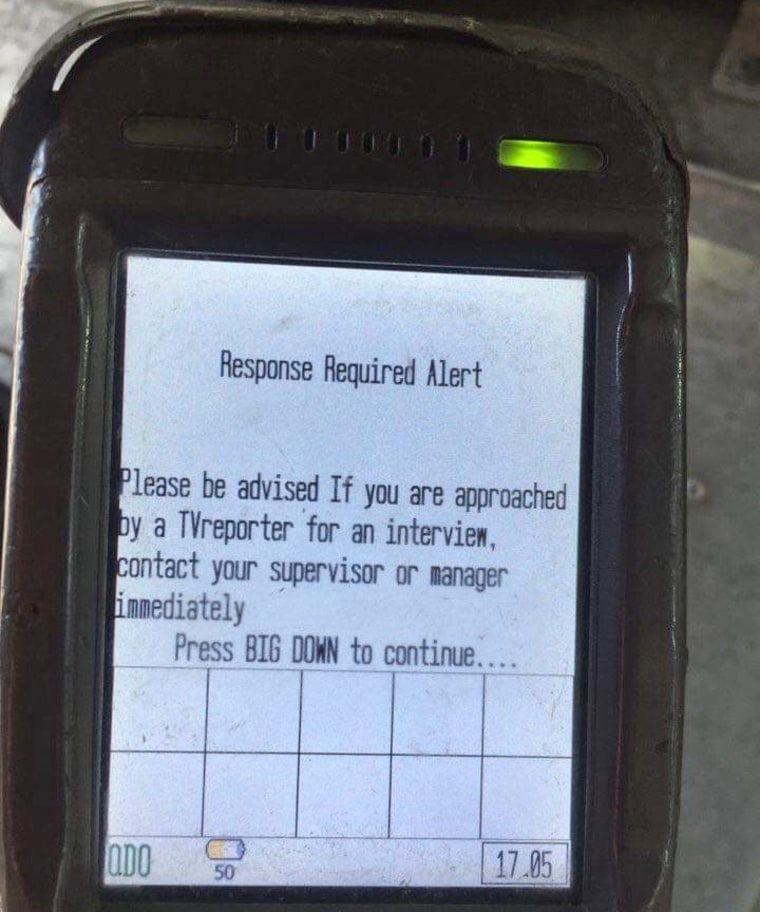

Many of those interviewed spoke on the condition of anonymity, saying they feared retaliation. In the days before NBC News ran its first story, workers were repeatedly told not to speak to the media, according to emails and messages. Employees and their families said they were speaking out because something needs to be done.

"It's just inexcusable," said the mother of a UPS driver in Texas, whose medical records show he fainted from heatstroke on the job in early August. "I don't want to watch him die because they think their packages are more important."

Gaut said the number of heat-related hospitalizations reported in July’s NBC News investigation affected less than one-tenth of 1 percent of the company’s driver workforce. "We have a robust heat injury prevention program implemented in 2006 called Cool Solutions,” he said. "We care deeply about the health and safety of all our people."

"The overwhelming majority of UPS drivers," Gaut said, "are well trained and effectively manage their health and well-being while working outdoors."

The Cool Solutions program encourages employees to hydrate, take proper breaks and report illnesses to supervisors.

"We never want them to continue working to the point that they risk their health or work in an unsafe manner," Gaut told NBC News in July.

Gaut denied that UPS discourages workers from seeking medical treatment. But according to some workers, supervisors don't always ensure employees get the necessary care.

A driver in Arizona recently spent more than 30 minutes cramping in a gas station as his requests for help went unanswered by supervisors, interviews and messages reviewed by NBC News show. He eventually contacted a union steward, who called 911.

Dalton Stovall, a driver in Texas, said he was instructed to pick up additional work at the end of a long day even after he told management he was cramping and didn't feel safe to keep driving.

A supervisor was in the truck with Stephen Nowlin in late June when Nowlin, also a driver in Texas, began to feel weak and faint.

That Friday was Nowlin's first day back at his Fort Worth workplace after two months out for a fractured foot. He says he had been promised a light route to help him ease in. Cool Solutions highlights the need for "proper acclimatization" when returning from leave.

But another driver called out sick, leaving Nowlin with a full load — 177 stops, at least eight hours of work. By 4 p.m., it was 94 degrees, and Nowlin could barely stand up.

"I couldn't even walk to the houses," Nowlin, 36, said. The supervisor had to take over running the packages to front doors.

They finished the day. When they got back to the center, Nowlin said, he started vomiting. He said management told him to cool off in an office — the only place with air conditioning. Nowlin thought he was OK, but when he got into his car, he fainted. He came to 40 minutes later, he said, and unsteadily drove home.

On Monday, he said, management insisted he come in. By 2 p.m., Nowlin was sick again.

"The only thing that was suggested to me was to go home and get some rest," Nowlin recalled.

UPS employees across the country said this is common. If a worker doesn't get medical care beyond first aid or miss work after an on-the-job injury, it's not considered "recordable" under federal rules.

That week, Nowlin took himself to the doctor, who diagnosed him with heat exhaustion and a head injury, according to his worker's compensation records. Doctors think the heat and fainting may have led to a neurological episode affecting his thought patterns.

"I'll catch myself forgetting how to make macaroni and cheese for my kids," he said. He hasn't been back to work full-time since June.

Following questions from NBC News, UPS said it is investigating Nowlin’s case, but that protocol was followed. "Mr. Nowlin was provided relief from his job at the time he reported feeling ill," Gaut said. "He did not ask for assistance to arrange health care at the time he reported feeling ill."

When it comes to heat, "time is of the essence," Dr. Ronda McCarthy, an occupational physician with Concentra Occupational Health, said. Heat exhaustion can progress to heatstroke, which can take a lasting toll on the kidneys, heart and brain. At its most acute, it can kill.

Yet drivers in Arizona, Georgia and Florida said that when they insist on medical attention, they're often taken to urgent care centers that contract with UPS. Many of those centers cannot administer IVs to rehydrate them or do blood work to diagnose kidney failure — delaying crucial treatment.

That's what happened to Mike Davis, 48, a driver in Longwood, Florida, on a sweltering day in mid-July.

After 27 years on the job, Davis knew that when he stopped sweating, it was a bad sign. He pulled into a grocery store lot and contacted his supervisors.

"I told them, 'You need to come get this truck,'" he said. He said his manager sent two people out, who asked if Davis wanted to keep driving, with a helper to drop the packages.

"I said, 'No, I need to go to the hospital,'" Davis recalled.

They took the truck, Davis said, and left him in the store.

He said about 45 minutes passed before a union steward picked him up.

When he arrived at his center, Davis said management suggested he go home and rest, a story confirmed by another co-worker. He insisted he needed to the emergency room.

Before they took him anywhere, they made him take a computer-based test about the signs of heat illness, he said. Only then did they take him to their occupational doctors at Centra Care, an urgent care center that NBC News confirmed does not administer IVs.

Doctors there took Davis' vitals, realized he was dangerously ill, and called 911. An ambulance took him to the ER, where he said he'd asked to go hours before. Records show doctors diagnosed Davis with extreme dehydration and elevated creatine kinase levels, a sign that the heat may have started to affect his kidney function. He was out of work for more than a week.

UPS said Davis was relieved of his work and arrived at a health care facility within 30 minutes of reporting he was ill. "He was mentally alert when requesting assistance," Gaut, of UPS, said. "After seeing the physician at the clinic, he was taken to a hospital via ambulance and after treatment, he was discharged that same day."

Davis is back on his route now. Last week, he and almost 30 other drivers in his hub worked 12-hour days in Florida's sticky heat.

"We're being pushed to the limit," he said.

Do you have a story to share? Click here to email us