DETROIT—“Giveaway Day” is underway at In The Trenches, a food pantry housed in a purple cottage amid run-down, burned-out homes and empty fields in a blighted Detroit neighborhood. Gospel pumps from the stereo as volunteers fill boxes with beefsteak tomatoes, lettuce, canned goods, frozen corned beef brisket and desserts.

Outside the pantry, a line grows—grandparents raising grandkids, single dads and moms waiting for food that many say will give them enough to eat until their next paycheck or disbursement of food stamps. It will also provide them a well-rounded diet with produce, including — later this year — much-needed vegetables from a unique source: a nearby farm run by a food rescue group dedicated to collecting food, including perishables, otherwise destined for the trash.

“They are so grateful for the fresh food,” said Alberta Hubbard, founder of In The Trenches, of her clients. “It's a blessing to see all of those fresh carrots, tomatoes. That's invaluable.”

Across the U.S., some food banks and rescue groups have moved beyond handing out meals to the needy. In recent years, they’ve started growing the food themselves, turning to full-scale farming to secure fresh vegetables for their food pantry clients. It’s a trend that began decades ago and which experts predict will grow, but since the work isn’t easy — it requires equipment, expertise, donations and volunteers — they believe it will continue to develop slowly.

Alberta Hubbard, aka “Momma Neighborhood,” Feeds Hungry Detroiters

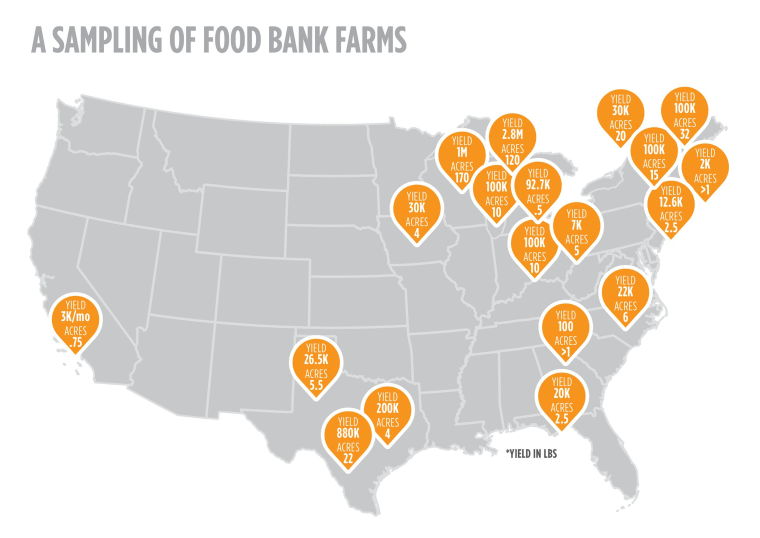

Currently, there are at least 18 food bank-run farms nationwide. They’ve sprung up in communities like San Antonio, Milwaukee, Hatfield, Massachusetts, and in Fenton, Michigan, about one hour’s drive northwest of Detroit, where the farm that supplies In The Trenches is located. The Hunger Task Force in Milwaukee was given a large farm once operated by a prison in a nearby suburb, while other food banks have been offered farmland by city government or local donors. And yet others, like the Food Bank of Western Massachusetts, bought land and made deals with farmers to cultivate it for them and take a share of the annual harvest.

“We have that commitment from field to fork, growing it and getting it moving through our system to the family,” said Eric Cooper, president of the San Antonio Food Bank, which is leasing 20 acres of farmland from the city for $1 a year over two decades.

That goal is shared by Forgotten Harvest, which is running the Fenton farm on 103 acres donated to the food rescue group for $1 a year by one of its board members. The group is trying to increase sustainable food supplies since most current sources “for us are uncertain going forward,” said Bill Bernstein, interim CEO and president.

“The traditional points of sourcing (such as grocery stores, restaurants and government programs) are trying to ratchet down their waste,” he added. “We’re not too sure that there’s always going to be some of this rescued food available.”

“You're tilling, you’re working ground, to fill somebody's stomach down the way."

The Fenton farm gives the food rescue flexibility in the kinds of crops that are cultivated and when they will be planted and harvested.

And it lets Forgotten Harvest stockpile produce for the winter, freezing and storing the vegetables at their processing center. Last year, the group stockpiled 70 percent of the total farm yield of 880,000 pounds.

“There’s not always nutritional, healthy produce available,” Bernstein said. “It’s just really diversifying the type and the sources of food available to us, and determining our own destiny in that sense.”

Food banks stepped in to address a steep increase in hunger in the early 1980s. But within about 15 years, obesity and diet-related illnesses, like diabetes, began to eclipse hunger as the major food problem, and aid groups came under criticism for relying too heavily on unhealthy processed goods, said Mark Winne, author of “Closing the Food Gap.”

“Food banks are responding,” he said. “They're trying to meet people's food needs, but at the same time they're trying to meet it with healthy food.”

Though it’s not commonplace for food banks or rescues to have large farms, like the one outside Detroit, Winne expects to see more of them.

“This has definitely gone to a different scale. It's not just a bunch of hippies and five acres,” Winne said, noting the equipment and infrastructure investments, and a level of professionalism that didn’t exist 20 years ago. “I think it's a very serious movement.”

Some food banks have made deals with farmers for a share of their harvest rather than get into running a farm – which is no small feat. The many challenges range from smaller troubles — deers gobbling up crops like sweet corn, a barn roof caving in, coping with older, donated equipment, and the whims of Mother Nature (a persistent winter delayed planting by a few weeks in the Midwest) — to larger issues that can prove more critical. In San Antonio, the food bank had to secure water for the crops amid ongoing drought (their neighbor, a salsa manufacturer, will funnel them their used daily vegetable wash totaling 5,000 gallons). Donations are also a must, including even for seeds, since money is a major factor, too. The farms can’t be money pits, many of the food banks said.

“We didn't want to take on something that would be an additional cost,” said Andrew Morehouse, executive director of the Food Bank of Western Massachusetts. Their most recent deal with a farmer on land the food bank owns means they pay just $700 a year in insurance while getting a share — about 100,000 pounds — of the harvest. “This model is all about it being self-sustaining,” Morehouse added.

One of the biggest keys to success is volunteers. At the Milwaukee and Fenton farms, some 3,000 people pitched in last year.

One volunteer at Fenton in early May was Cathy Gillis, a 65-year-old retiree. She swept dirt off long ribbons of black plastic bags snaking through a field. The plastic, tucked in the earth, is a simple solution to warm the soil, keep out weeds and provide an ideal growing pod for the 40,000 cabbage seedlings that would soon be planted here. But the plastic needs to stay in good condition to be effective.

"It's hard work. You sweat a lot," said Gillis as she paused, broom in hand under sunny skies and ankle deep in dirt.

She said that when the farm began last year, she asked, "Why are we doing this?" considering the large food rescue operation already run by Forgotten Harvest. But she realized why after the crops – squash, zucchini, cabbages and more – came in and the trucks rolled out from the farm filled with produce destined for folks like those at In The Trenches. "That's where you really start to see the actual benefit of having this land," she added.

With her bounty, she will make carrot soup, glazed carrots, carrot salad, carrot cake and carrot bread. Nothing goes to waste.

And Forgotten Harvest wants to grow that: it’s aiming to more than triple this year’s yield to 2.8 million pounds – about 6 percent of the food they expect to hand out this year.

“We're not thinking about profit as much as we're thinking about the aspect of where it's going,” said Kevin Clark, assistant farm manager, as he smoothed soil for the first of 500,000 carrot seeds to be planted. “You're tilling, you’re working ground, to fill somebody's stomach down the way. You think about it every day when you get here.”

An estimated 49 million Americans have limited or uncertain access to enough food to meet their daily needs. Families say they have to stretch benefits they receive to make ends meet, especially after last year's decision by Congress to let lapse a temporary funding boost to the key government food aid program known as SNAP (Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program). But even before that, low-income Americans said they needed to spend 10 percent more dollars a week in 2012 than in 2011 to give their families three meals a day, according to a recent report by Feeding America, a national hunger relief charity to which many food banks belong.

With their limited purchasing power, low-income families say they stock up on belly fillers like meat and potatoes rather than lower-in-calories fruits and vegetables. Produce is also prohibitively expensive for the poor.

Such unhealthy, cheaper calories were contributing to high rates of heart disease, diabetes and obesity, said Cooper of the San Antonio Food Bank.

“Sometimes people think obesity is overconsumption. But it’s poor nourishment,” he said. “If we're going to sustain good health for the future, we have to be able to have greater access to healthy food.”

Northern Neck Food Bank in eastern Virginia said it began working with farmers three years ago after a survey revealed that people in 32 percent of the households it serves had either Type 1 or Type 2 diabetes.

“It was really kind of jarring,” said Lance Barton, the bank’s chief executive officer. The bank moved aggressively to form agricultural partnerships — though they opted out of running a farm — telling farmers, “We really need your help.”

“It’s very clearly the future," he added of the farming. “This is what people deserve - not only to live but to live well.”

Reginald Bray, a client and volunteer at Detroit’s In The Trenches and a single dad, says he struggles to decide how to spend his limited resources. Last fall, his food stamps were cut due to missing a sign-up deadline. Now he and his three-year old daughter live on his $800 a month disability payment — $400 goes to rent, $175 to utilities. That leaves about $200 a month for everything else, including food. "If we have to make a choice, either put some meat on the table or buy some produce, we would choose the meat. A lot of us would not be getting those fruits and veggies if it wasn't for this," said Bray, 46, on a break from helping carry boxes of produce.

On “Giveaway Day,” Bray would go home with his own produce. And so would Margaret Bennett, who is raising three of her grandchildren. At her house in Detroit's "Downriver" neighborhood, where a home caught on fire the night before and the one next door bears a sign reading, “For sale $9,000 or best offer,” Bennett marveled at the bags of carrots from the pantry. With her bounty, she will make carrot soup, glazed carrots, carrot salad, carrot cake and carrot bread. Nothing goes to waste.

Bennett, 57, took in her grandkids a few years ago. They live off her $721 in disability (plus another $721 they receive for her grandson who is legally blind), with $650 going to rent and another $600 to utilities and cable. Each month, she stocks up on staples, using most of her $300 in food stamps on 10 boxes of cereal, 10 gallons of milk and two family bundles of meat.

Her financial predicament makes Bennett even more reliant upon the pantry and farm for fresh produce that her grandkids love, especially in the winter. But on this day, she is pleased with the carrots and a supermarket fruit platter she collected at the pantry. Bennett has laid it out as an after-school treat for her youngest grandchild, Diane Theodore, 5, who she says loves fruit. And as soon as the girl runs through the door in her charter school uniform, her ponytail askew, nothing could be more clear.

Using two plastic forks at the same time, the kindergartner feasted on pineapple, watermelon, grapes, cantaloupe, mango and honey dew melon. Fruit juice dripped down her chin as she spoke and ate. "I'll eat this whole thing," Diane said nearly halfway through the platter. No doubt, her grandmother agreed. But first, Diane ran outside to ride her bike in a light rain and then quickly returned for more.

“She'll eat fruit before she will eat any kind of junk,” Bennett said, noting Diane always requested fruit for breakfast. “If a child tells you they need this and want this, it means a lot.”

Is your community doing a similar project? Email the reporter with the story: miranda.leitsinger@nbcuni.com