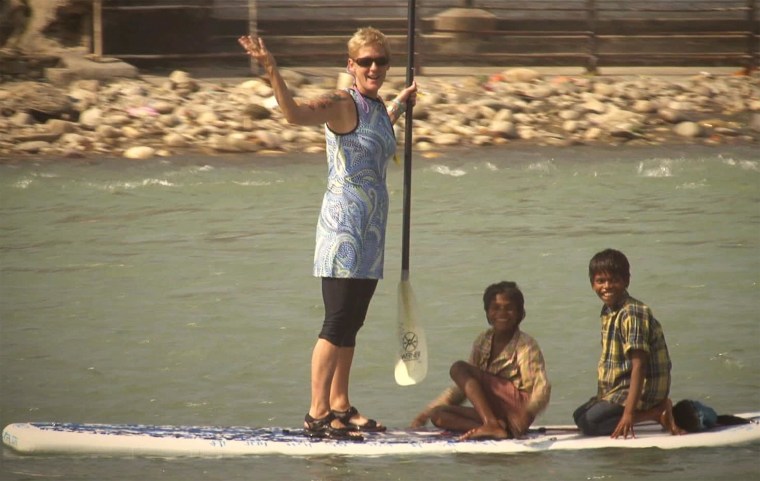

When doctors told Michele Baldwin that there was nothing more they could do to treat her cervical cancer, the single mother of three decided to devote what time she had left to one extraordinary feat and a life-saving message. She left her home in New Mexico for India and became the first woman ever to paddleboard 700 miles down the Ganges River. She did it bring attention to HPV and cervical cancer; she did it to help other women avoid her fate.

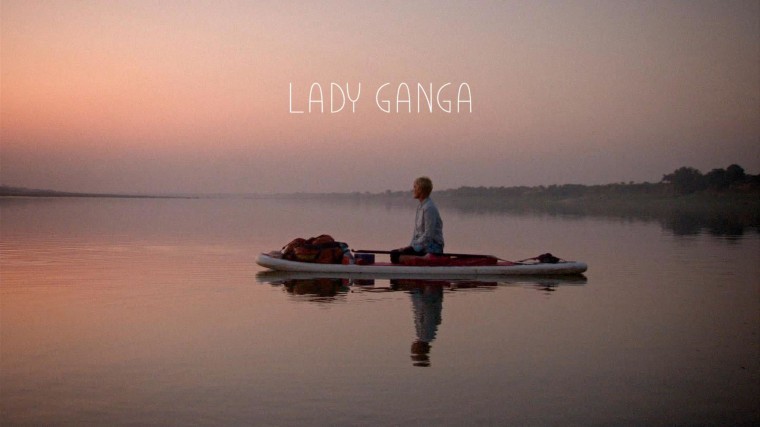

Baldwin completed her odyssey on the Ganga in November 2011, but in some ways her story was just beginning. Shortly after her return, and less than two months before she died, Baldwin was contacted by Frederic Lumiere, a filmmaker who wanted her to participate in his documentary, “Someone You Love: The HPV Epidemic.” Their initial two hour phone call sparked not only an instant friendship but an entirely new film.

“Her story was so exotic and epic,” says Lumiere, “I realized she needed her own film. It was about even more than cervical cancer, it was about accepting your destiny, coming to peace with it, and doing something incredible with your life.”

It was Baldwin’s wish that Lumiere document the end of her life, no-holds-barred, and with his co-producer Mark Hefti, he did exactly that, interviewing her friends and family, and capturing unfiltered footage of her final weeks.

Baldwin wanted people to understand exactly what it is to die of cervical cancer, which, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, is highly preventable and almost always caused by the human papillomavirus (HPV), for which there are vaccines. About 79 million Americans are currently infected with HPV, and most sexually-active men and women will get at least one type of HPV in their lifetimes.

Michele died on February 5, 2012 at 45-years-old, but the film that will continue her mission is just now taking its first steps; Lumiere and his co-producer Hefti are currently raising funds on Kickstarter to complete it, and they plan to have it ready by summer 2015.

Here, Lumiere shares the grief and responsibility he felt following her death and explains how her example has inspired him to live differently.

When Michele talked to you about her hopes for what the film would achieve, what did she say?

The most obvious part of her message was that she wanted people to know about cervical cancer and that HPV causes cervical cancer and that it’s preventable. And she wanted to put that message out there, especially in countries like India where more than 70,000 women die of cervical cancer each year. So that was the medical message: vaccinate your sons and daughters; get your Pap tests.

But there was another part of her message which was timeless and that was the way she accepted her destiny and chose to take her tragedy and turn it into something positive.

This woman embraced her fate with a grace that I had never seen before.

I have to tell you, I have met a bunch of people in different situations who say that they accept their situation, but this woman embraced her fate with a grace that I had never seen before. I am convinced that her journey down the Ganges river -- an incredible journey which involved a lot of time alone -- I’m convinced the result was that she realized, “This is my destiny. Now, what do I want to do with it?” And she was able to slowly transform her family by teaching them to be able to detach from their strong feelings and get on board with her quest to save other women. Each and every one of them knew that this was Michele’s wish, and I saw it in their eyes; this is what kept them together. They saw that it was bigger than them, that it was bigger than her.

We see many raw moments with Michele as she becomes sicker. It seems like she had no vanity about people seeing that.

She was a beautiful woman, and she would try to put on her makeup here and there, but towards the end, there was a moment when makeup didn’t matter anymore, nothing mattered anymore. It almost felt like a sacrificial action on her part: “Here I am. Film it all.” When I went back the last time to see her, her mother said to me, “Frederic, I’m really sorry, but I’m not going to let you film Michele anymore; I don’t want anybody to see her like that.” And of course, I had to respect that. But that night, I sent her an email and I quoted Michele’s words about what she wanted the film to do; Michele knew that the shock factor would get people to pay attention.

In her whole journey down that river, she was surrounded by death, and I think it really helped her accept it. She wasn’t afraid of it anymore.

You know, the Ganges river -- the Ganga as they call it -- is a burial ground for people who can’t afford even an open pyre; they let the body float away in the river. Michele told me that when she paddled down the river, and she first saw a dead body floating, she stopped and called the authorities, and they kind of laughed and said, “No, no, you don’t understand. This is what people do.” So, in her whole journey down that river, she was surrounded by death, and I think it really helped her accept it. She wasn’t afraid of it anymore.

Culturally, we have a difficult time with death, we don’t talk about it; we’re often uncomfortable around very sick people. What do you think is the lesson to be learned from how Michele dealt with it?

I think the example she set is that death should not be taboo; it’s as much a part of life as being born. There is not one human being in the history of mankind that has not experienced death, and if you have a strong faith -- whether you’re Buddhism, Christian, Muslim, or whatever -- it can be beautiful. She really got the people around her to accept death in its raw form.

She obliterated the taboo by confronting it head on. She didn’t want people to feel uncomfortable with the fact that she was going to die in front of them.

One of the obvious ways she did that was having an open pyre funeral. It’s a very different way to see a funeral, and she invited all of her friends and family. I would say that almost none of them were Buddhist, so it was the first open pyre that any of these people had ever been to; it was definitely my first. The other thing she did that was very touching was that she used humor. She got her friends and family used to the idea of her being dead with humor. She obliterated the taboo by confronting it head on. She didn’t want people to feel uncomfortable with the fact that she was going to die in front of them.

What was it like for you when there was no more filming to do?

When I finished shooting, it messed with me; I’m not going to lie. It stayed with me in a very unexpected way. I was incapable of working on the film, not because it was tough to watch it -- I was used to that -- but because I didn’t think I was up to the task. I didn’t think I could do it justice. I just didn’t think I could match what I had felt on the screen or that I could honor her sacrifice and her legacy. I started maybe 25, 30, 40 different cuts, and every time I thought, “That’s not good enough.” Eventually, my friends and my wife convinced me to go and see a therapist, a wonderful woman, and she said, “You’re grieving. Allow yourself to grieve.” It took a while, but finally I was able to go back.

When I finished shooting, it messed with me; I’m not going to lie. It stayed with me in a very unexpected way.

Did you see new sides of Michele as you began to look through the footage, something that perhaps you didn’t see while you were shooting?

Yes, definitely. I didn’t realize how incredibly profound and timeless some of what Michele had said was until I revisited it in the edit. And I also realized that Michele had been in charge the whole time.

She was not going to compromise on this thing. How could you compromise when it’s the very last thing that you’re going to do? You have to go all out, and that’s exactly what she did.

There is a scene where she is talking to her brother; he was having a very hard time with it and he was there to pour his heart out to her. We were in the other room to give them space, but she called out to me, “You’re probably going to want to film this, Frederic, so get him to sign a release, and put a mike on him.” That’s just one example of how she was in complete control. She was not going to compromise on this thing. How could you compromise when it’s the very last thing that you’re going to do? You have to go all out, and that’s exactly what she did.

What was your happiest moment filming with her?

There were many nights where we would just sit and talk about a bunch of stuff, and one night we were talking about how many stuffed animals she had and how that was pretty embarrassing for a grown woman. I told her that when I was a kid I only had one stuffed animal: a blue elephant. She loved that story for some reason, she was intrigued by the idea of a blue elephant. Anyway, in the morning I came back, and her son, who she hadn’t seen in a couple of days, had brought her a stuffed animal, and it was a blue elephant. She couldn’t believe it. She really was just amazed. When she was dying, she stayed very, very close to that blue elephant. She said to me, “After I die, I want you to have that blue elephant. I want you to give it to your kids.” My daughter has it now.

How did your time with Michele change you or what would you say was her greatest lesson to you?

When her doctors told her she had just a few months to live, Michele decided to do just that. Listen, any of us could die without warning, and in a way Michele had a little bit of a blessing because she was told when her death would be and she chose to use her time incredibly wisely and do what really mattered to her. I know it sounds cliche, but if you can take that kind of thinking and apply it to your life today, imagine what you could do. That’s exactly what I’m doing. I started changing my career after I met her. I started turning down projects that I felt were not consistent with my vision of how I want to spend my time and the kind of things that I want to do for the world. And just watching the response to this Kickstarter campaign, you realize that you can make a film that will change the world in some way. And moving forward, those are the only kinds of films I want to work on, and I thank Michele for that.

This interview has been edited.

For more information and inspiration visit MariaShriver.com