LGBTQ families made headlines twice this month, but for very different reasons.

Last week, a study found that from a mental health perspective, adult children with lesbian parents fared just as well as their peers with opposite-sex parents. This follows an Italian study released in May that found that children with same-sex parents were actually slightly better off psychologically than children with a mom and a dad.

"In our current climate, we’re at risk of backsliding on this issue ... We need to be ready to contest that, and now we can do it in a scientific way."

Earlier this month, however, Republican lawmakers dealt a blow to LGBTQ people seeking to become parents. The House Appropriations Committee approved an amendment allowing foster care and adoption agencies that receive federal funding to refuse to work with same-sex couples on religious or moral grounds. Though the amendment has several steps to go before becoming federal law, 10 states already have a similar law in place.

The House amendment goes even further than current state-level laws. It would cut 15 percent of child welfare funding to states that explicitly prohibit agencies from excluding LGBTQ people.

Independent and private adoption agencies that do not receive federal funding are already allowed to deny LGBTQ people.

The studies of children with same-sex parents don’t surprise advocates of LGBTQ families. Zach Wahls, who was born to a lesbian couple through artificial insemination and famously defended same-sex parents to the Iowa Legislature in 2011, said it was exciting to have studies to back up his experience.

“In our current climate, we’re at risk of backsliding on this issue,” Wahls told NBC News. “We need to be ready to contest that, and now we can do it in a scientific way.”

Scientific as they may be, the studies are unlikely to move those who advocate for allowing agencies to exclude LGBTQ families, because the objections are faith-based and do not pertain only to lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender people.

"We think about having more kids, and it’s upsetting, that there’s another hurdle now."

The House amendment, and many of the state laws, are broadly written and can allow exclusions of anyone based on religious criteria, such as single parents or religious minorities, like the Miracle Hill agency in South Carolina, which recently refused a Jewish family. The broad language of the amendment also opens the door to denying a range of child welfare services to children and parents who don't meet religious criteria.

Advocates of permitting religious objections say LGBTQ families can simply turn to other agencies that will work with them.

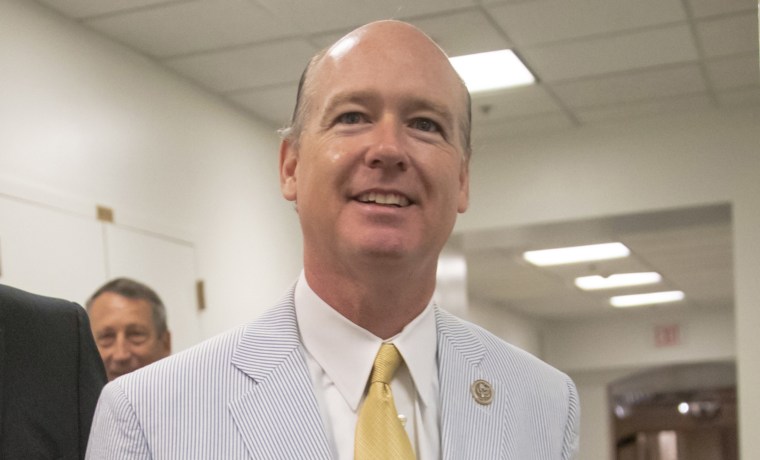

Rep. Robert Aderholt, an Alabama Republican who authored the House amendment, posted to his website a statement from conservative think tank Heritage Foundation that pushes back on critics' claims about the amendment.

“The other side is falsely saying that this prevents LGBT couples from adopting. That’s not true. They are still welcome to foster and adopt from a plethora of agencies,” said Melanie Israel of the foundation.

But that isn’t exactly the case for Kristy and Dana Dumont, a lesbian couple in Michigan suing the state. In a video discussing their case, the Dumonts describe their desire to foster a child, and how they were turned away by their local agencies that contract with the state.

The Dumonts' attorney, Leslie Cooper of the American Civil Liberties Union, said that when the couple decided to adopt a child out of foster care, they had two choices of agencies to work with locally, but neither accepted same-sex couples. She said the Dumonts could work with agencies elsewhere in the state, but they didn't want to pull a child from his or her local area.

“When families get turned away, and maybe don’t have the fortitude to keep knocking on doors multiple times and keep facing the humiliation,” Cooper said, “it’s the children who lose out on a loving home.”

Cooper argued that agencies contracting with the state to find families for children in state custody must value the children’s needs over the agency’s religious beliefs.

Religious-freedom advocates say forcing faith-based agencies to permit LGBTQ people to adopt hurts foster children by reducing the number of agencies in operation. Some faith-based agencies have shut down rather than work with LGBTQ families.

Catholic agencies are currently suing the city of Philadelphia for forcing them to comply with non-discrimination policies.

On his website, Aderholt expresses concern about agencies closing.

“My goal was straightforward: to encourage states to include all experienced and licensed child welfare agencies,” Aderholt’s statement reads. “We need more support for these families and children in crisis, not less.”

Julie Kruse, federal policy advocate at the Family Equality Council, an LGBTQ family advocacy group, said faith-based agencies' shutting down does not limit children’s options, because other agencies simply fill the void. She cited a report from the Human Rights Campaign that reviewed government data.

In Massachusetts, for example, from 2004 to 2006, an average of 42 percent of children in state custody were placed with a family in less than one year. From 2007 to 2009 it went up to 47 percent, even though Catholic Charities, the agency involved in the Philadelphia lawsuit, pulled out of adoptions there in 2006. The 10-year average, from 2004 to 2014, was 46 percent.

Issues of religious freedom are a source of anxiety for some LGBTQ people, who worry that their rights will be rolled back in the name of religion. But facing legal uncertainty is nothing new for many in the community.

Andrea and Rebecca Bickett live in Mississippi, a state that allows discrimination against LGBTQ people on religious grounds, and not just in adoption.

They went through the process of adopting their twin 5-year-old sons, Owen and Adrian, three times to make it legal. First, one of them adopted the boys as a single woman. Next, they did a second-parent adoption, then a stepparent adoption. Two years ago, following the nationwide legalization of same-sex marriage, they both adopted their daughter, Regan, in a single process, becoming one of the first same-sex couples in the state to adopt a child after the state’s ban on same-sex adoption officially ended.

The landscape appeared clear for fostering or adopting another child. Then, the law allowing LGBTQ exclusions took effect in October of last year.

“We think about having more kids, and it’s upsetting that there’s another hurdle now,” Andrea Bickett said.

But she was encouraged by the study showing that children of same-sex parents are just as well off as their peers.

“I think that was pretty cool,” she said. “We are normal, we are no different than any other family.”

Wahls, the advocate from Iowa who is now running for state Senate there, said that is a growing sentiment.

“The overall trend has been positive,” Wahls said. “I used to get more concern about my moms, but now people just ask me how I learned to shave.”

FOLLOW NBC OUT ON TWITTER, FACEBOOKAND INSTAGRAM

CORRECTION (July 26, 2018, 3:28 p.m. ET): An earlier version of this article misstated the way that Zach Wahls was conceived. It was by artificial insemination, not in vitro fertilization.