It’s been 50 years since the historic Stonewall uprising, the 1969 rebellion at a Greenwich Village gay bar widely credited with igniting the modern-day LGBTQ rights movement.

But did it?

Stonewall’s monumental impact is not in question, but marking it as the start of the gay right’s movement erases those who fought for LGBTQ right before that fateful June night five decades ago, historians say. Before Stonewall, there was a nascent — but growing — “homophile movement,” mostly of gay men and lesbians, who formed groups to fight for their rights in the early 1950s. As the decade progressed, so, too, did their defiance.

“I hope that out of all the attention being given to Stonewall on this 50th anniversary that people learn that Stonewall was not the start of the LGBTQ civil rights movement — that it was a key turning point,” Eric Marcus, creator of the award-winning “Making Gay History” podcast, told NBC News.

Marcus admits that for a while even he didn’t know there was a gay rights movement before Stonewall, but when he started researching, documenting and archiving the lives of lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender people around the county, he “came to discover that there was a 19-year history prior to Stonewall.” Those years, he and other historians have asserted, set the stage for what became the most famous LGBTQ uprising in U.S. history.

The pre-Stonewall “homophile movement,” didn’t start with a bang or a brick, Marcus said, it started with people meeting in their living rooms, the blinds drawn, discussing the issues they were facing and knowing something needed to be done. Usually, Marcus added, they were separated by gender.

“The first organization founded principally for men was the Mattachine Society in 1950” in Los Angeles, Marcus said. Five years later, a similar group popped up in San Francisco, the Daughters of Bilitis. Started as a social organization, it morphed into a political body for lesbians. Both organizations started publishing newsletters and setting up chapters around the country, though they were limited in scope.

“Homosexuals had no credibility in the popular arena,” George Chauncey, a Columbia University history professor and author of “Gay New York,” explained. “It was very difficult for them to speak for themselves.”

The Mattachine Society and the Daughters of Bilitis had to try to build support for their cause from people who were respected and had authority, Chauncey added. So they reached out to sociologists, lawyers, judges and scientific researchers, hoping to convince people to help them dispel the prevailing myths that stigmatized gay people.

In the early days of the Mattachine Society and the Daughters of Bilitis, “it was assumed that gay people were mentally ill,” Marcus said.

“The first person to challenge that in a serious way was Dr. Evelyn Hooker when she … compared a group of 30 gay men to 30 straight men,” he said. “She presented her study in 1956 at the American Psychiatric Association convention in Chicago, and she just about blew the roof off the place, because she said that there was no difference in terms of psychopathology between gay men and straight men.

Homosexuality would ultimately be removed from the American Psychiatric Association’s list of mental illnesses in 1973, but Marcus said Hooker’s study “got the ball rolling.”

In addition to building support from experts and authority figures, the Mattachine Society and Daughters of Bilitis also provided social services to gays and lesbians.

“You had hundreds of people around the country who felt pretty isolated, writing these organizations,” Chauncey said, “asking if they had contacts wherever they lived or what would it be like to move to a city.”

But as the 1960s approached, the groups grew more militant.

One of the people responsible for this change was Frank Kameny, who was fired from his job in the Army Map Service in 1957 after President Dwight D. Eisenhower signed an executive order essentially banning gay people from federal jobs. Marcus said tens of thousands of people lost their jobs during what was known as the Lavender Scare. Most of them just wanted to disappear and not let anyone know they were fired for being gay — but not Kameny.

“Frank decided to fight his government,” Marcus said, which “brought the movement from behind closed doors into the public eye.”

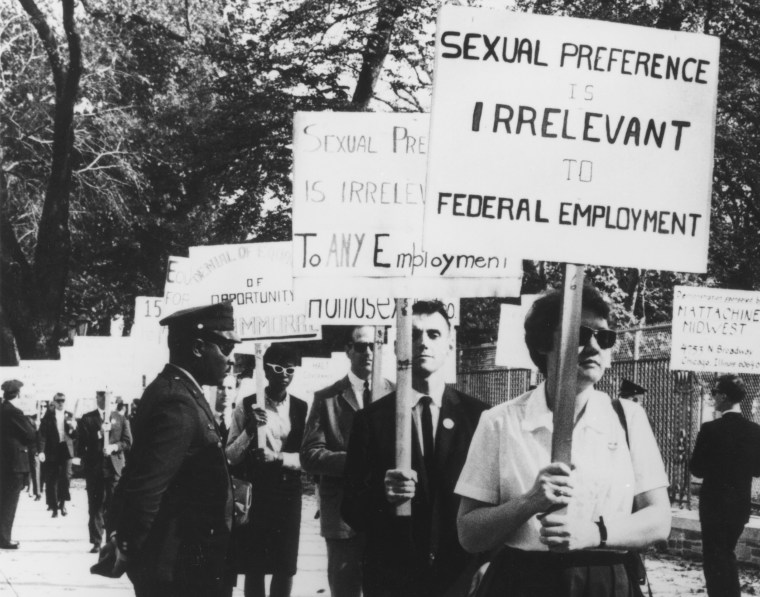

Kameny founded the Washington chapter of the Mattachine Society and turned it into an organized and aggressive protest group. From 1965 to 1969, Kameny and the Mattachine Society protested outside the White House and Independence Hall.

“His whole career was destroyed,” Chauncey said, and he “dedicated the rest of his life to fighting for gay rights and to end the kind of discrimination he'd faced.”

As more people got the courage to come out as gay, as tough as it was in the 1950s and ’60s, the policing of the community started to ramp up. The unjust firings, bar raids and ongoing public humiliation led to an increased desire to fight back.

As the ’60s progressed, the early “homophile” groups got stronger. Kay Lahusen, now 89, was a member of the Daughters of Bilitis and joined Kameny’s gay rights protests in D.C. and Philadelphia.

“We were picketing for the standard civil rights thing,” she told NBC News. “The right to fair employment, the right to serve in the military, the right to teach school.” Lahusen said not all of those early gay activists approved of the public protests, but she, Kameny and the others were undeterred.

As the groups grew emboldened, they started to look toward the black civil rights movement for inspiration. One example was the 1966 “sip-in” at a bar in Greenwich Village that was organized by the Mattachine Society.

“They were modeling this on the sit-ins that courageous, young, black college students organized in the South in the early ’60s,” Chauncey said. “They said they were homosexuals and would like a drink.”

The sit-ins caught the public’s attention. “It didn't have a practical effect right away, but it was important in helping to shift public opinion,” Chauncey explained.

As varying social movements grew, so, too, did the gay rights movement. And some of the groups joined forces.

Many of those who became gay rights activists, Chauncey said, “had been involved in the antiwar movement, the feminist movement, the New Left Black Power, and they brought the militance of those movements and the radical analysis that those movements were developing into gay politics.”

Stonewall was certainly a historic turning point, but it wasn’t even the first major LGBTQ uprising. In 1966, in the Tenderloin district of San Francisco, after a trans woman who was resisting arrest threw a coffee cup at a police officer in the Compton Cafeteria, transgender and gender-nonconforming people rioted. The group, many of whom were sex workers, fought back against the police, asserting their right to exist in a public space.

To truly honor the legacy of Stonewall, historians say, we also have to honor those who laid the groundwork for it to happen.

Editor's note: All four episodes of "Stonewall 50: The Revolution" will be posted to nbcnews.com/nightlyfilms throughout June. To see more LGBTQ archival images, visit The New York Public Library's "Love & Resistance: Stonewall 50" page.