This year New York City will host dueling pride marches on the same day: the official NYC Pride March and the activist-run Queer Liberation March.

The schism that resulted in two separate events on June 30, the last Sunday of LGBTQ Pride Month, is the product of a longstanding political disagreement within the community: whether pride is a demand for acceptance and integration into broader society or whether it’s a radical demand for the liberation of all LGBTQ people.

For those paying attention, this tension has been on full display during the past two NYC Pride Marches — while the roots of the broader debate go back decades.

In 2017, activists used a “lockdown” technique to halt the official march in front of the Stonewall Inn to protest the presence of corporations and uniformed police. The NYPD was forced to arrest 12 activists outside the Stonewall, where a police raid in 1969 helped spawn the modern LGBTQ rights movement — a raid that the department only apologized for this year.

Then, before last year’s march, a group of activists calling themselves the Reclaim Pride Coalition delivered a set of demands to Heritage of Pride, the nonprofit that has produced the NYC Pride March since 1984.

Reclaim Pride told Heritage of Pride that if it wanted to allow police to participate, the officers had to be out of uniform and unarmed. The activist group also demanded that there be no barricades along the sidewalk of the march, to ease congestion and allow passersby to join the massive annual event. Reclaim Pride also demanded that a “resistance contingent” be given a place near the front of the march to highlight the LGBTQ community’s opposition to the Trump administration’s policies.

“Reclaim Pride Coalition believes that HOP’s management of the annual NYC Pride March, resulting in commercial and police saturation of the March among other unacceptable characteristics, has led to decades long conflict with and the alienation of many individuals and groups within the NYC LGBTQ community,” the group wrote last year.

When Heritage of Pride responded to those demands a month before the 2018 NYC Pride March, Reclaim Pride activists were incensed: The march was shortened, the route was reversed and no changes were made to the presence of police officers or barriers. In addition, Heritage of Pride distributed wristbands for officially sanctioned marchers.

This year, with the 50th anniversary of the 1969 Stonewall uprising and the addition of WorldPride to the city’s events, millions of additional people are expected to descend on New York City the last weekend of June. And Reclaim Pride will be holding its first Queer Liberation March — a separate, police-free, anti-corporate, unsanctioned event that will take place just hours before the official NYC Pride March.

Organizers from both groups spoke to NBC News about their views on Pride. They represent a historic divide that was present even before the Stonewall uprising of 1969: whether the LGBTQ rights movement is a revolutionary one or one seeking integration into the American body politic.

RECLAIM PRIDE'S VIEW

Natalie James, a co-founder of the Reclaim Pride Coalition, said the reason New York needs the Queer Liberation March is because of what Stonewall really was about.

“What was different about Stonewall, in terms of New York City leading up to that time, was the massive response to the brutality,” James said. “People fought back, and they fought back not just for one day, for multiple days.”

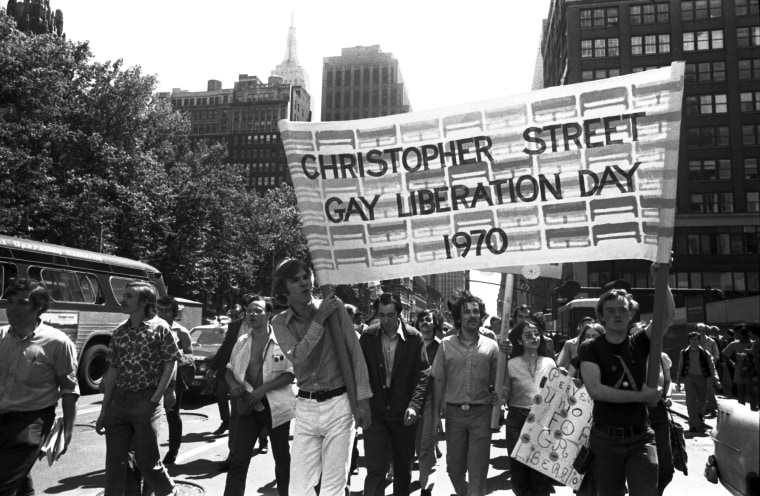

The barriers now set up by police for crowd-control purposes prevent passersby from joining the march, James said. During the first pride march in 1970, called Christopher Street Liberation Day and held on the anniversary of the Stonewall uprising, marchers shouted, “Off of the sidewalks, into the streets!” — and people listened. By the time marchers entered Central Park, the event’s last stop, the crowd stretched for blocks.

We're not going to change the world again if we just sort of go along with the program.

Martha Shelley GLF founding member

Several veterans of the early LGBTQ movement agree with James and have thrown their support behind the Queer Liberation March, including Fred Sargeant, one of the organizers of the first pride march, and the activist Martha Shelley.

“I can see the Heritage of Pride point of view, that they need money to pull off a huge party and all that sort of thing,” Shelley told NBC News. “I'm also seeing from the Reclaim Pride point of view that we're not going to change the world again if we just sort of go along with the program.”

Shelley, a founding member of the Gay Liberation Front, which was founded right after the Stonewall raid, said she is dividing her time between the dueling groups.

“I am going to be the Gay Liberation Front spokesperson at the Heritage of Pride rally on Friday night,” she explained. “And then on Sunday, I’ll be marching with Reclaim Pride.”

When she speaks Friday, Shelley said she’s coming with a political message: “We have to deal with a vast economic inequality and corporate control of our political and economic system.”

“When Gay Liberation Front started, we were a tiny little group of raggedy-ass kids,” Shelley said. “We were, with one or two exceptions, all under 30. We didn't have careers to lose, and yet we changed the world.”

During its brief existence from 1969 to 1973, the Gay Liberation Front reached out to all sorts of other revolutionary liberation groups, including the Black Panthers, according to Shelley.

“The previous gay organizations were kind of single-issue groups and weren't making those alliances,” Shelley added, referring to integrationist groups like the Mattachine Society, which had staged an annual, lightly attended picket protest in Philadelphia.

“By doing that — by changing the attitudes on the left first — we eventually changed the entire culture,” Shelley said.

HERITAGE OF PRIDE'S VIEW

Heritage of Pride contends that there is no way to pull off the massive NYC Pride March — which is expected to draw an estimated 4.5 million people this year — without police, barricades and some level of corporate partnership.

“I understand on some level where Reclaim Pride is coming from, but I also have been an event organizer in New York City and I understand that to do a large-scale event like our march, logistically, you can't do it without barricades,” Sue Doster, director of strategic planning at Heritage of Pride, told NBC News. “You can't do it without police, and in New York City, if you get a permit for an event of this scale, you automatically get police, you automatically get barricades.”

Doster said that even though the parade’s corporate presence is a far cry from the small group of marchers that first stepped off from the Stonewall Inn in 1970, it is particularly meaningful for people all around the world — particularly those in homophobic countries where LGBTQ people are still demanding basic rights. Doster recounted a discussion she had with an LGBTQ activist from Kenya: “She said to me, ‘Seeing what you do in the United States, even before I came here, seeing the pictures, gives me and my friends hope, because for us it shows us how it can be.’”

When Doster started volunteering with Heritage of Pride in the 1990s, “we literally cut out letters and made our own banners," she said. "Now, of course, we have mass-produced banners that are vertical on light poles down the entire route — very, very different.”

“When we were making our banners, we actually hung them ourselves,” she added. “We climbed the ladders with ropes and duct tape and attached them to the top of light poles all along Christopher Street.”

Now, the packs of protesters verbally harassing marchers as they paraded past St. Patrick’s Cathedral have been replaced by supportive spectators packed 10 deep on sidewalks along the entire route, according to Doster.

“And the truth of the matter is, regarding sponsors, Pride has gotten more and more expensive over the years,” Doster explained. “A lot of our attendees really want big names, and that is expensive. It's a balancing act, and I think we at Heritage of Pride are very conscious that it's the community’s, so that it's not T-Mobile’s event or TD Bank’s event.”