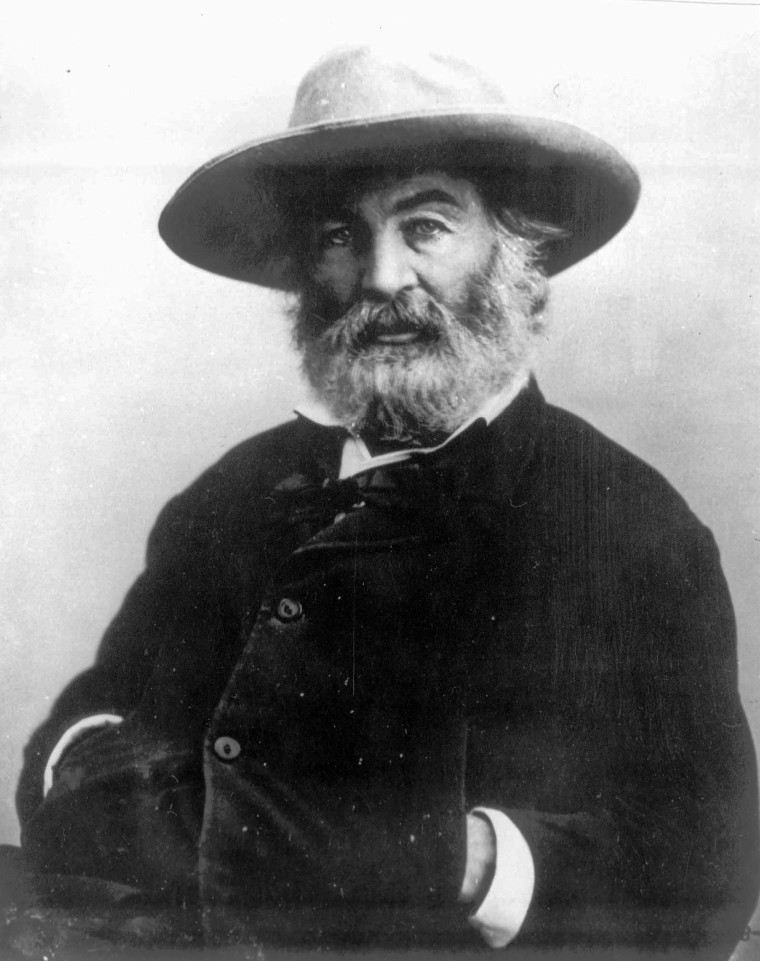

Walt Whitman never publicly addressed his sexual orientation in his poems, essays or lectures. He lived from 1819 to 1892, a time when “gay” meant little more than “happy.”

Biographical materials, however, note he was involved for decades with a man named Peter Doyle. And in works like the "Calamus" poems in his "Leaves of Grass" collection, Whitman discusses romantic and sexual relationships between men.

As California looks to implement the country’s first LGBTQ-inclusive curriculum, state education officials and textbook publishers are grappling with how to refer to figures like Whitman, who were believed to have been gay, bisexual or transgender but never came out: Should we label them as such?

While advocates have argued for the importance of highlighting the historical contributions of LGBTQ people, others have objected to imposing contemporary terms on people who lived long before they were introduced.

The outcome of the debate stands to potentially affect the education of millions of children in California — home to one of the largest public education systems in the country — and could set a model as other states move toward requiring more inclusive teaching materials.

FAIR Education Act

The 2011 Fair, Accurate, Inclusive and Respectful Education Act, a state law known as the FAIR Education Act, requires that California public schools teach about LGBTQ people and people with disabilities. Its passage has sparked a years-long curriculum review process to incorporate these figures into the state's history textbooks.

This month, California's State Board of Education (SBE) approved 10 such textbooks for students in kindergarten through eighth grade, saying in a statement that the books include a “more complete picture” of the accomplishments and challenges faced by LGBTQ figures in California and U.S. history.

But the SBE also rejected two textbooks, both published by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt (HMH), on the grounds that these books and accompanying materials failed to properly highlight the sexual orientation of people like Whitman, Emily Dickinson, Ralph Waldo Emerson and President James Buchanan.

“The absence of specific labels regarding sexual orientation creates an adverse reflection because the identity of these individuals is not honored and demeans their contributions to history,” a state-appointed commission told HMH, according to the news site EdSource.

Leah Riviere, a spokesperson for the publisher, said that while HMH “fully supports and respects” the FAIR Education Act, the facts and presentation in its history and social science textbooks must be based on “clear, verifiable historical evidence.”

“The contemporary terms (LGBTQ), when applied without additional historical context, may not map directly onto past lives and experiences, and also may not reflect how individuals identified themselves during their lifetimes,” Riviere said in an email to NBC News.

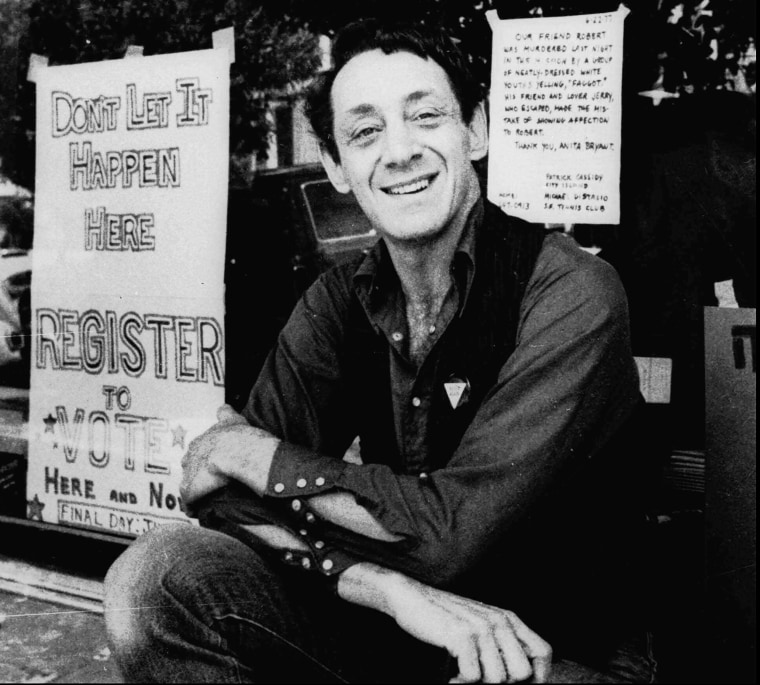

HMH materials identify Harvey Milk, one of the country’s first openly gay elected official, as gay, because Milk publicly labeled himself as such. But when it comes to someone like Florence Nightingale, an English social reformer and the founder of modern nursing, Riviere said the publisher is more hesitant to use the term “lesbian.”

“Some scholars speculate that she might self-identify as a lesbian if she were alive today based upon the intimate nature of her correspondence with several women during her lifetime,” Riviere said. “Because this cannot be verified as fact, HMH offers additional context for educators but does not add a formal label.”

According to scholars, the term “homosexual” did not enter common usage until the early 20th century, while “gay” became popular in the 1930s and ’40s, and “lesbian” emerged in the 1970s. Nightingale lived from 1820 to 1910.

As the state reviewed textbooks meant to fall in line with the FAIR Education Act, a collection of LGBTQ advocacy groups began to advocate for a curriculum framework that would show that people of all sexual orientations could go on to make history.

“It’s not about projecting a contemporary name on a historical figure but about enabling people’s lives to be part of the study,” Polly Pagenhart, the communications and policy director at Our Family Coalition, told NBC News. “For kids who are LGBTQ, recognizing that a historical figure had a life partner who was a fellow man or a fellow woman … is so powerful.”

McGraw Hill, which was one of the publishers to have an LGBTQ-inclusive textbook approved by the state, did refuse some of the state commission's requests for changes. For example, in first-grade materials, it pushed back on the commission's request to refer to Ellen DeGeneres as "a lesbian and humanitarian," instead writing that DeGeneres "works hard to help people."

"She and her wife want all citizens to be treated fairly and equally,” according to EdSource.

But Pagenhart argued it is important to identify someone like DeGeneres, who publicly identifies as a lesbian, by her sexual orientation the same way that a person of color might be described by his or her race.

“If a person isn’t closeted, there’s no need for a history book to be closeted about them either,” Pagenhart said. “You’re assumed to be heterosexual unless you’re named otherwise.”

“If a person isn’t closeted, there’s no need for a history book to be closeted about them either."

Polly Pagenhart, Our Family Coalition

McGraw Hill also rejected the California commission’s recommendation to list the poet and Harlem Renaissance leader Langston Hughes as gay, saying there is no evidence to support the claim.

Catherine Mathis, a McGraw Hill spokesperson, said in a statement to NBC News that the publisher considers labeling issues on a case-by-case basis — “taking into account privacy concerns of the person being identified and providing information that is appropriate for the age of the student.”

Acts vs. Identities

Marc Stein, a history professor at San Francisco State University who has written extensively about LGBTQ history, said scholars tend to separate individuals’ acts and desires — of which there often is some kind of historical evidence — from their identities, communities or movements, which tend to take on actual labels.

“In the era before there was any notion of same-sex sexual identity, it does a disservice to the specificity of historical periods to project or impose current terms,” Stein said. “On some level, many of us would argue that there were no gay people or lesbians before the terms existed.”

Susan Stryker, a history and gender studies professor at the University of Arizona, said she will describe historical figures as partaking in transgender practices but will not say they had transgender identities.

For instance, she said she uses he/him pronouns to discuss the stagecoach driver Charley Parkhurst — who was assigned female at birth but lived as a man — and treats Parkhurst's life as part of transgender history. Parkhurst lived from 1812 to 1879, while the label "transgender" is thought to have been coined in the latter part of the 20th Century.

California's inclusive curriculum includes fourth- and eighth-grade history lessons on Parkhurst, who had initially dressed as a man in order to participate in the Gold Rush but maintained this identity long after.

When it comes to applying this discussion to the classroom, Miriam Morgenstern, the co-founder of History UnErased, said that a top priority should be ensuring that students learn that people of all sexual orientations can make history.

Morgenstern’s organization, based in Massachusetts, looks to promotes LGBTQ-inclusive history curricula, like the one mandated by the FAIR Education Act, nationwide.

“We feel like teachers and schools can contextualize LGBT history and look at this as something that’s just a fabric of society, how we’ve developed as a people and as a nation,” she said. “It’s important for all students, not just LGBTQ students.”

And ultimately, “pushing for inclusivity and visibility,” Morgenstern said, “that’s what’s most important.”

While California's new and more LGBTQ-inclusive textbooks may be available as early as next fall, the debate about assigning specific gender and sexuality labels to historical figures is likely to continue long after.