A new Alzheimer's drug was granted full approval by the Food and Drug Administration on Thursday, marking the first time the agency has approved a drug meant to slow the progression of the disease.

The drug, called Leqembi, was shown in clinical trials to slow the progression of Alzheimer’s disease in people with mild cognitive impairment or early-stage illness. It is not a cure.

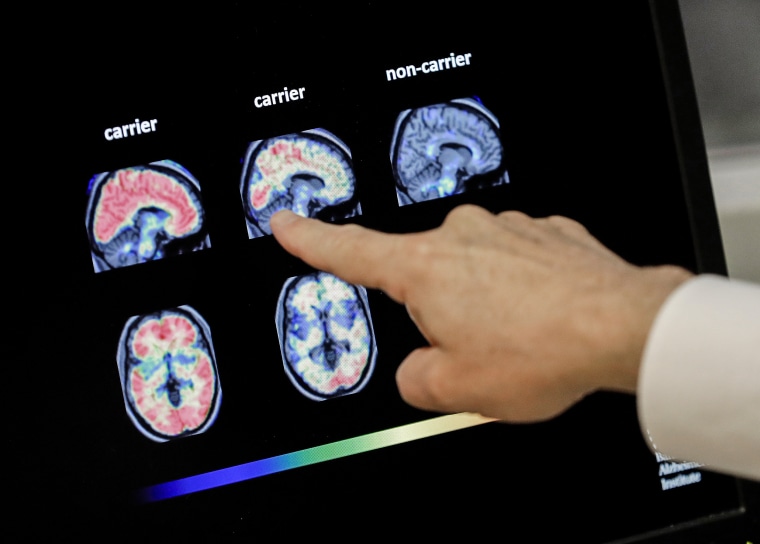

Leqembi targets a type of protein in the brain called beta-amyloid, long thought by scientists to be one of the leading causes of the disease.

It's given every two weeks as an infusion, so patients will need to visit a hospital or clinic twice a month for the treatment. It also comes with a hefty price tag: $26,500 a year.

While Leqembi offers hope to patients and their families, experts say that there are still some key unanswered questions about the drug, including about its safety and effectiveness.

Here are questions experts still have about the Leqembi.

Will patients notice a difference?

Though clinical trials found that Leqembi slowed the progression of Alzheimer's disease compared to a placebo, experts have called the drug's effect "modest" and said it's unclear whether it will lead to noticeable changes in people's daily lives.

In the drug's Phase 3 clinical trial, researchers looked at cognitive decline over 18 months in nearly 1,800 people who were given either the drug or a placebo.

Cognitive decline was measured using a scale that focused on how well patients fare in six areas: memory, orientation, judgment and problem solving, community affairs, home and hobbies, and personal care.

For each category, patients are on a 5-point scale: 0 is normal, 0.5 is questionable dementia and 1, 2 and 3 are mild, moderate and severe stages of dementia, respectively.

The rating method is “very subjective,” said Dr. Ronald Petersen, a neurologist at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, because the scores are based on questions the researchers posed to patients. That said, it is currently the best method researchers have to quantify the severity of symptoms in patients, he said.

Researchers added up the scores and then looked at how much they changed over the course of the trial in people who were given Leqembi compared to the people who were given a placebo.

At 18 months, patients in the Leqembi group scored on average 1.21 on the clinical dementia scale and the placebo group scored 1.66, a 0.45 difference or 27% slower rate of decline.

That difference is small, said Dr. Alberto Espay, a neurologist at the University of Cincinnati College of Medicine, and below the threshold of what would be clinically meaningful to a patient.

It is unlikely that patients or their families would "be able to tell the difference," he concluded.

Petersen, however, was more hopeful. "It doesn't stop the disease, it doesn't make it any better, but it might delay the rate of progression," he said.

Who will benefit from Leqembi and for how long?

Leqembi is only approved for patients with mild cognitive decline or who are in the early stages of Alzheimer's.

A sub-analysis of Eisai’s clinical trial data found the drug appeared to work better in older people compared to younger people and in men versus women, puzzling Dr. David Rind, a primary care physician and the chief medical officer for the Institute for Clinical and Economic Review, a group that determines fair prices for drugs.

“It makes you wonder whether lecanemab is doing something we don’t completely understand yet,” he said, using the generic name for Leqembi.

Donna Wilcock, the assistant dean of biomedicine at the University of Kentucky, said more research is needed.

“The short answer is: We don’t really know why this would be at this point,” she said. “We can all try to speculate on what that means,” but ultimately the findings will need to be further investigated in additional studies.

Still, the sub-analysis is not a reason to not offer Leqembi to certain groups, Wilcock said. "I think there's enough information and that the decision really should be down to the doctor and the patient."

Besides questions about who will benefit the most, there are also questions about how long the drug will benefit patients.

Eisai's Phase 3 results only looked at the drug's effects over 18 months. It's unclear how effective the drug will be after a longer time period, Petersen said.

The 27% slowing could "have an increasing impact over 24 months or 36 months or 48 months and could be more meaningful down the road," he said. "I don't think it's actually accurate to portray this as a linear effect out forever."

Wilcock said many colleagues she has spoken with are also "quite confident" the positive benefits of the drug will increase over time.

How safe is Leqembi?

According to the FDA, Leqembi can lead to brain bleeding or brain swelling — side effects that are particularly concerning to researchers after reports of three deaths of patients who got the drug. In response to the first two reports of deaths, Eisai has denied a link to Leqembi.

The drug's approval came with the FDA's strongest safety warning — called a boxed warning — about the brain bleeding and swelling, which can be life-threatening in some cases.

Petersen said brain bleeding and brain swelling are likely caused by how the drug works: It removes amyloid from brain cells, but, in the process, it also removes amyloid from the walls of blood vessels, which can make the brain "leaky."

The side effects are also seen with another Alzheimer's drug, Biogen's Aduhelm, which also targets amyloids, Wilcock said.

About 12.6 % of patients who got Leqembi in the clinical trial developed brain swelling, compared with 1.7% of those in the placebo group. About 17% of the Leqembi group experienced brain bleeds, compared with 9% in the placebo group.

The company noted that many of the people who were found to have brain swelling didn't have any symptoms as a result.

Because Eisai's Phase 3 trial only went for 18 months, it's unclear how prevalent the condition may be, or if it becomes more common the longer a person takes the drug, Espay said.

The reports of brain bleeding and brain swelling "may only be the tip of the iceberg," he said.

The condition is "potentially very serious," Petersen said, "there’s no doubt about it."

He said people who get Leqembi will need to be monitored closely, but added the side effects should be manageable.

Follow NBC HEALTH on Twitter & Facebook.