For years, Meghan Neri paid $30 apiece for packages of epinephrine auto-injectors for her two adolescent children with food allergies. The price for four packs of the lifesaving medication was a manageable $120 a year.

So Neri, 42, of Scituate, Massachusetts, was shocked when, in 2019, her family pharmacist said that each auto-injector pack would cost $600.

Her out-of-pocket cost for the year had skyrocketed to $2,400.

The price of the epinephrine shots themselves had not risen. The problem was the Neris had switched to a new, high-deductible health insurance plan to save money. Monthly payments are lower with high-deductible programs, but families must pay thousands of dollars each year before many costs — often including epi auto-injectors — are covered.

Like the Neris, many families are caught off guard by the jump in price. Some are forced to ration the auto-injectors or go without them.

“Many families have opted not to pick up their EpiPens because they can’t afford it,” said Dr. Purvi Parikh, an allergist and immunologist at NYU Langone Health in New York City. “They’re taking the chance that, God forbid, a bad outcome will occur.”

Parikh said families have had to shoulder more and more financial responsibilities over the past decade, particularly as high-deductible insurance plans have become more common.

The 2010 Affordable Care Act expanded access to health insurance, so companies were faced with covering more people than ever before. To compensate, insurers “not only raised how much it costs to be covered, but they’ve pushed more of that out onto the patient in the form of high-deductible plans,” Parikh said. “We’ve been seeing this every single year for at least the last seven to 10 years.”

An analysis by KFF, also known as the Kaiser Family Foundation, found that in 2009, 17% of workers were enrolled in a health plan with an annual deductible of at least $1,000. By 2021, it was 50%.

“The average deductible in employer-based health insurance now is over $1,700 per person,” said Larry Levitt, executive vice president of KFF.

With some family plans, deductibles can soar well over $3,000.

“What it means is that even when you’re insured, you may not actually be protected from potentially catastrophic health care costs,” Levitt said.

Prescriptions that previously cost no more than $30 or so — a basic copay — are now full price, which can soar into hundreds of dollars.

Some medications, such as drugs to control high blood pressure, are covered even before the deductible is met. But the epinephrine auto-injectors — which deliver a shot of epinephrine and are the only emergency medicine available for life-threatening allergic reactions — usually are not.

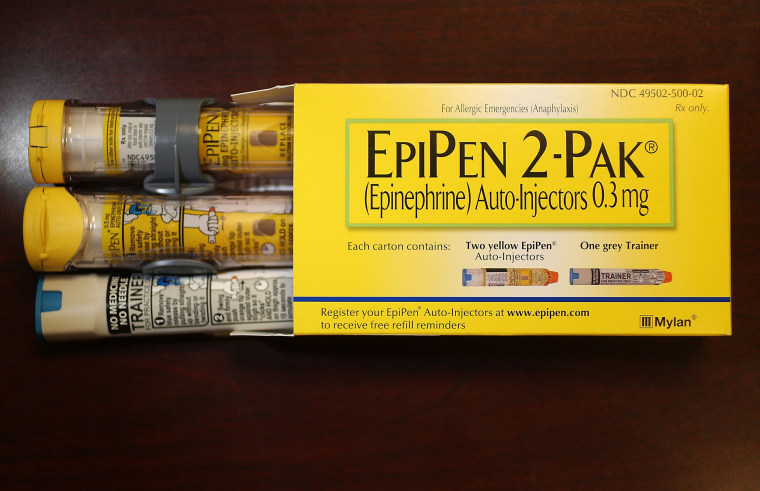

Few prescription drugs or devices symbolize out-of-control health care costs more than EpiPen.

From 2008 to 2016, Mylan pharmaceutical company raised the price of its auto-injectors by more than 400%, leading to public outrage and congressional scrutiny.

Other epinephrine-delivering products soon emerged, such as Adrenaclick and Auvi-Q, along with generics, with the hope of creating prices more people could afford. It worked, to a point.

“The amount that privately insured patients had to pay out of pocket did decrease,” said Dr. Kao-Ping Chua, an assistant professor of pediatrics at the University of Michigan Medical School and the Susan B. Meister Child Health Evaluation and Research Center in Ann Arbor, Michigan.

Side effects: More on drug costs in the U.S.

- Mark Cuban's next act on drug costs: Tackling insulin.

- Video: A new gene therapy could help children with an inherited blood disorder. The cost: $2.8 million.

- $35 price caps on insulin to take effect in January. Most people with diabetes won't benefit. Why?

- Inflation Reduction Act: How it will affect your health care.

But after switching to a high-deductible plan, some patients like the Neris discovered they were charged nearly full price for epinephrine auto-injectors.

Neri’s daughter, Shea, 14, has a milk allergy, and her son, Thomas, 12, is allergic to milk, peanuts and tree nuts. They do not leave home without the devices nestled into a small fanny pack they wear at all times — just in case of an exposure.

“You hope that it’s wasted medicine and wasted energy,” Neri said.

The injectors are only good for one year, on average. The Neri family must purchase four auto-injector packs for the two children each year to keep in their home and schools. Shea and Thomas have each had to use the emergency epinephrine shots.

When the pharmacist told Neri the new price for the refills, she was devastated and did not pay the $2,400 that day.

“It was a little embarrassing to say, ‘I can’t do this right now,’” she said.

Deductibles are intended to discourage improper use of medical care and abuse of prescription drugs, Levitt said. But epinephrine auto-injectors save people’s lives.

“No one is using them inappropriately,” he said.

Indeed, Neri said the auto-injectors are necessary tools to protect her children.

People don’t expect to pay this much when they have health insurance.

Pediatrician Dr. Kao-Ping Chua, University of Michigan Medical School

“This is not a choice. Nothing about this is a choice,” she said.

Epinephrine is the first line of defense when a person has a severe allergic reaction, called anaphylaxis. When this occurs, blood pressure plummets. Airways narrow, making it hard to breathe. A shot of epinephrine, or adrenaline, can reverse what could otherwise be deadly.

“For high-value, lifesaving medications, there should be zero cost out of pocket,” said Chua, of the University of Michigan.

Chua has spent years studying how much families pay for emergency epinephrine. He led a study published in July that found 1 in 13 patients were paying more than $200 a year for their epinephrine auto-injectors.

Most were children, in part because allergies are more prevalent in kids than adults, but also because they need multiple auto-injectors to store at home, at school and during after-school activities.

A majority of the families paying more than $200 a year in Chua’s study — 62.5% — were enrolled in high-deductible health plans.

“I view this primarily as a problem of insurance benefit design,” Chua said. “People don’t expect to pay this much when they have health insurance because they assume that insurance will cover the medication.”

Patients can question high prices

“It’s typically up to insurers — and employers in the case of workplace health benefits — whether any health care services and drugs are exempt from the deductible,” Levitt said.

Health insurance companies could exempt epinephrine auto-injectors from their high deductibles. UnitedHealthcare announced that starting next year, there will be no copay or other out-of-pocket costs for epinephrine on some of its plans.

It’s the only major health insurance company to cover epinephrine so far, but “we are increasingly seeing a trend towards insurance companies waiving out-of-pocket costs for patients for drugs that are lifesaving,” Levitt said.

Chua said it would be good public policy to limit the cost of other lifesaving drugs, too, such as insulin for diabetes and naloxone to reverse opioid overdoses.

But AHIP (formerly known as America’s Health Insurance Plans), a group that represents such companies, said drug manufacturers are to blame.

“We encourage Big Pharma to end their price gouging tactics and lower their out-of-control prices for patients,” the group said in a statement to NBC News. “Patients need their life-saving medications, so a lack of medication choices mean that Big Pharma has no incentive to agree to lower prices.”

Ultimately, navigating health plans and scrambling to figure out ways of paying for expensive medications is left to patients.

“The most important thing to know is whether or not they have to pay a deductible for drugs before insurance coverage occurs,” Chua said.

After that day in the pharmacy, Neri took a close look at her family’s health insurance plan and contacted their physician to talk through other options.

They switched to a different brand of emergency epinephrine and now pay $25 per pack.

“We were going to spend what we needed to keep them safe,” Neri said. “But it’s helpful to have enough information to make an educated decision and not feel like you’re throwing money away unnecessarily.”

Levitt said that patients should feel empowered to question high prices.

“It’s a lot of work,” Levitt said, but “if you’re faced with a claims denial, if you’re faced with a high cost, fight it. Fight it with your health care provider, fight it with your insurance company.”

“No almost never means no in health insurance,” he said. “You can often win.”

Follow NBC HEALTH on Twitter & Facebook.