PINEHURST, N.C. — From the time Sgt. 1st Class Richard Stayskal heard about Special Forces dive school, he knew it was for him. The 35-year-old Army Green Beret had been drawn to the military by its mission and purpose and the dive school appealed for the same reasons. "I had heard how tough the school was and knew a few divers and they were all great guys," Stayskal said. "I wanted to work with guys who would subject themselves to such a rigorous course. To me, it showed character."

Before starting, Stayskal was required to undergo a CT scan of his lungs. A bullet had torn through his chest during a 2004 tour of duty in Iraq and left scar tissue. He needed the all clear to be sure his wounds wouldn't compromise safe underwater operations.

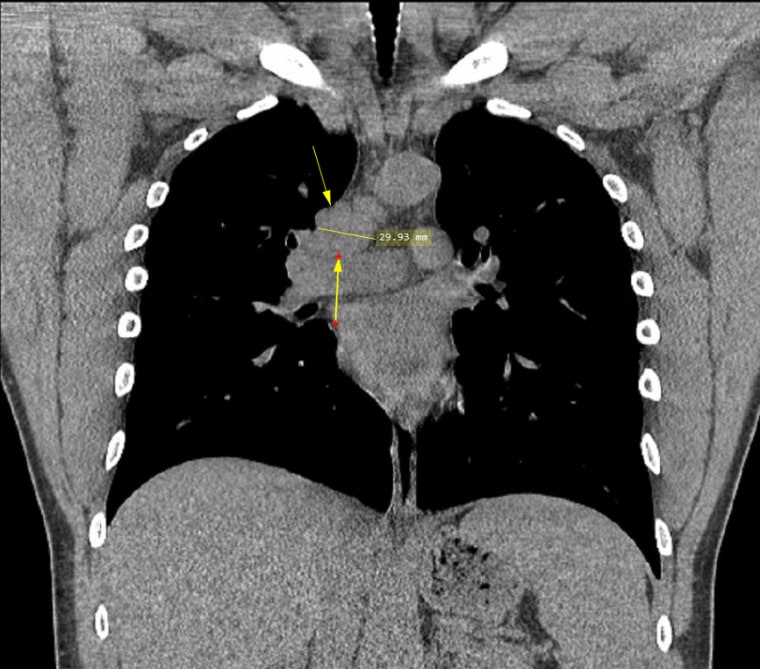

In January 2017, Stayskal reported to the Womack Army Medical Center, an Army-run hospital at Fort Bragg. He had the scan but no one noted a mass in his right lung — a tumor more than an inch in diameter.

Four months later, Stayskal was rushed to the Womack ER in an ambulance. He was having chest pains, wheezing and felt dizzy. His wife, Megan, met him there. The doctors took a look at the earlier scan and this time noticed the tumor, writing "Abnormality: Attention Needed" in the medical record. Still, Stayskal was sent home with a diagnosis of "atypical pneumonia," three prescriptions, and a referral to a military hospital pulmonologist for evaluation.

By June, Stayskal was coughing up blood and obtained special permission to go off the military base to see a civilian specialist. Dr. Michael Pritchett, a pulmonologist, gave Stayskal his first accurate diagnosis: Lung cancer. Stage 3.

"The fact that he went six months without a diagnosis allowed that cancer to grow and very likely advanced its stage," Pritchett told NBC News. From the first scan in January to the one in Pritchett's office, the size of the tumor had nearly doubled.

"They robbed me of six months," said Stayskal. "Six months of untreated time…"

Stayskal's cancer is now Stage 4, and terminal.

The Feres Doctrine

But Stayskal can't hold the military's doctors accountable in court. A 1950 Supreme Court ruling followed by decades of case law known as the Feres Doctrine prevents active-duty service members from suing the federal government for medical malpractice. For years, the doctrine has survived one legal challenge after another, effectively preventing military families from seeking redress in the courts.

The number who have had cases blocked is unknowable but could be vast. Some cases were dismissed in lower courts, others on appeal. Many were dissuaded from even filing. But the ruling has affected all active duty service members over the past seven decades and there are more than 1.3 million on active duty today.

The Stayskals were stunned. They understood a ban on lawsuits related to injuries on the battlefield, where split-second medical decisions are necessary. After all, Stayskal had been shot in Iraq and treated at a combat hospital. He was awarded a Purple Heart for "wounds received in action." But in this case, doctors at a stateside hospital had missed his cancer diagnosis. If a civilian patient like his wife or daughters had received negligent treatment at that same military hospital from the same doctors, they would have the right to sue.

As the Stayskals searched for avenues to pursue, they learned of story after story of lawsuits that had been blocked. Navy Seaman Danyelle Luckey, 23, died of sepsis shortly into her first tour aboard the USS Ronald Reagan amid allegations that doctors failed to treat her symptoms in a timely manner. Navy Lt. Rebekah "Moani" Daniel, 33, bled to death after childbirth at a Washington state military hospital in 2014. Her husband, Walter, a former Coast Guard officer, filed a wrongful-death lawsuit. A federal appeals court said, "If ever there were a case to carve out an exception to the Feres doctrine, this is it." But in May, the Supreme Court declined to hear it.

The Stayskals found one of the few lawyers willing to take on Feres cases, Natalie Khawam of the Whistleblower Law Firm in Tampa. "If we can't better the standard of care for our troops, then what kind of country are we?" Khawam said. "How can we ask service members to protect us, but we can't protect them?"

Since so many legal challenges had failed in the courts, the best course, Khawam believed, was to get Congress to pass a law. So Richard and Megan left their two young daughters at home and joined Khawam on Capitol Hill to lobby Congress. A half dozen trips later, Stayskal told his story in an emotional hearing before a subcommittee of the House Armed Services Committee on April 30.

"It's long past time that Congress fix this injustice," said Jackie Speier, D-Calif., who chaired the hearing and introduced a bill in Stayskal's name that day. The Sergeant First Class Richard Stayskal Military Medical Accountability Act of 2019 would carve out an exception to the Feres Doctrine for medical malpractice in non-combat cases. "The current law denies servicemembers the same rights held by their spouses and families, all other federal workers, and even prisoners," said Speier.

Since then, getting the bill passed has become a second mission for Stayskal. In between cancer treatments, he makes the 330-mile drive to Washington, D.C. nearly once a month. He's met with dozens of lawmakers and staffers, officials at the Pentagon and spoke briefly with President Donald Trump and Vice President Mike Pence at a rally in Greenville, N.C., this summer.

The president told Stayskal "he'd definitely look into it," according to Stayskal, and asked about his prognosis.

Opposition to the original Supreme Court decision goes back decades and comes from across the political spectrum. "Feres was wrongly decided and heartily deserves the widespread, almost universal criticism it has received," conservative Justice Antonin Scalia wrote in a dissent to a 1987 case. More recently, Justice Clarence Thomas wrote this when the Court denied Walter Daniel's petition in May: "Unfortunate repercussions … will continue to ripple through our jurisprudence as long as the Court refuses to reconsider Feres."

While it is difficult to know how many cases were barred or dropped by the doctrine, a conservative estimate of meritorious claims would be in the hundreds, says Andrew Popper, professor of law and government at American University's law school. "Year after year, perfectly legitimate and often heartbreaking cases are filed and courts, often with statements of regret, are required to dismiss them," said Popper, who published a law review article calling on Congress to act. "We should not accept the premise that one willing to fight and die for a system of justice should be denied access to the system."

The Feres Doctrine defended

The Department of Defense defends the current system of medical accountability and compensation, maintaining that regardless of who is at fault, benefits are paid and every injury or death is treated the same "whether caused by combat, training accident, household accident, natural cause, or other reason."

If an exception to the Feres Doctrine were carved out for medical claims, courts could award extra compensation for certain injuries or deaths. Other cases, like those involving combat injuries, would not be eligible.

The DOD opposes such a carve out. "The combat injury or death would appear to be valued lower than an injury or death where a tort claim would be allowed," DOD spokesperson Lisa Lawrence said in a statement. "Such an inequity toward members injured or killed in military operations or a wide range of other circumstances could not be sustained."

Read the full DOD response here.

"What we are talking about is what works best for national defense," said retired Maj. Gen. John D. Altenburg, a former deputy judge advocate general of the Army, who has testified before Congress in support of Feres. "They are making sure the soldiers can train and be focused on their mission, which is operational readiness. Litigation is a civilian court would be a "distraction" and "disruptive," he says.

Under the current system, it makes no difference if there is negligence, Altenburg points out. "The only thing that matters is you got hurt while you were in the military and you are going to get the compensation that the system provides."

The Defense Department claims that more malpractice suits would likely bring defensive medicine practices into military health care. "It can include performing excess tests and procedures that are not necessary for the patient, may harm the patient, and increases costs to the Department," a DOD spokesperson wrote in an email. "This affects military readiness by increasing time a Service member is…away from duty."

But in Stayskal's case, an extra test might have changed his prognosis. "The chance for a cure is better at an early stage," Pritchett told NBC News. "We'll never know what would have happened if we would have caught it six months earlier."

Womack Army Medical Center, where Stayskal was screened in January and treated in May, told NBC News it does not discuss specific case details with the public, but noted it is "required to identify, analyze and appropriately report unanticipated outcomes, and take requisite corrective actions."

"Womack AMC is committed to providing the highest quality care in the Military Health system," the Center said in a statement. "We continue to support Sgt. 1st Class Stayskal in his ongoing medical treatment."

The end of the mission

"I used to think, jokingly, when I was wounded in Iraq that I paid my price. I was going to be good. I was going to live to be 90," Stayskal said. But he is now 38 and the picture looks quite different. His cancer is incurable.

"I won't be able to walk my daughters down the aisle, never see my grandkids, not grow old with my wife," he said. "You get silly thoughts like, are your parents going to have to bury you? That's hard to think about."

Stayskal still drives an hour to Fort Bragg every day, where he works with Green Berets on skills training. He is grateful for the backing of his commanders. It saddens him that he will never again deploy and experience the life of a Special Forces soldier — the training, the camaraderie, the chance to lead and mentor.

He spends as much time as he can with his daughters, Addison,12, and Carly, 10, coaching softball and watching gymnastics competitions. He's been accepted to a clinical trial. Every other Sunday, he flies to Moffitt Cancer Center in Tampa for scans, labs and an IV drug cocktail. Always on his mind is the legislation that could change the future for his fellow soldiers.

If we can’t better the standard of care for our troops, then what kind of country are we?

Natalie Khawam

Although the Stayskal bill has bi-partisan support and the endorsement of many military and veterans' organizations, it may not be enough. The proposal passed the House as part of the broader National Defense Authorization Act, the annual Pentagon policy bill, currently under negotiation in the House and Senate. But Sen. Lindsey Graham, R-S.C., whose support as chair of the Senate Judiciary Committee is critical to preserve the provision, voiced his opposition in October. "I have been a military lawyer for 33 years," Graham said in response to a question from a Fox News affiliate. "The deal is: You sign up for the military, you get disability, you get benefits, your family gets well taken care of and you're not able to sue. … I think it's a trade-off that's stood the test of time."

But Stayskal remains hopeful. He and his lawyer have had a phone call with Graham. "I just hope we convinced him why he should support the bill," he said.

Stayskal wants the law to be his legacy. He wants his daughters to remember that he took the hard route. "I hope one day they will understand that I'm doing this for so many others and this is something that can't continue." He wants to leave the military better than he found it.

"It's really just what I try to teach my kids, you know? So many great things have happened in this country over time. And all because somebody said, "'Hey, this isn't right. And I'm going to fix it.'"

Kit Ramgopal, Kara Stevick and Jaime Longoria reported from New York.