Kingston Brown, 8, woke up in his Augusta, Georgia, home last weekend complaining of a headache and gulping for air. His mother rushed him to a nearby hospital, where he vomited in the lobby.

"I don't want to die," he told her.

When his father, Michael Brown, saw Kingston, the boy was pale, but his oxygen level was steady.

"That's the thing that scared me the most. Out of all of the times that I encountered him having one of these episodes," Brown said of Kingston, who had experienced an asthma attack and was hospitalized overnight at Augusta University Health, "he's never had one this bad and mentioned death."

An estimated 25 million people in the United States have asthma, but for those like Kingston, who is Black, their condition can be dire. Health data collected in recent years has indicated a growing imbalance along racial lines: Black people and Native Americans are diagnosed with asthma at higher rates; emergency department visits related to asthma are five times as high for Black patients as for white patients; and Black people are about three times more likely to die from asthma than white people.

The concern among doctors and patient advocates to ensure adequate treatment and access to care comes as the asthma death rate appears to be climbing.

Asthma deaths across the country rose by more than 17% from 3,524 in 2019 to 4,145 in 2020 — the first "statistically significant increase" in more than 20 years, according to federal data examined by the Asthma and Allergy Foundation of America, a nonprofit patient organization that tracks hospital visits and asthma-related mortality rates; it plans to include its findings in an annual report this fall.

For years, the asthma death rate has declined, in part because of better diagnosis and medications.

Kenneth Mendez, the foundation's president and chief executive, called the year-over-year jump "puzzling" for a disease that is largely manageable through an array of treatments, and said further studies are needed to understand why the number of deaths increased and if a lack of proper care or a severity in cases were to blame.

While Covid-19 may also be a likely factor in the recent increase, there's more to be studied as a warming climate and hotter days are only worsening the effects on people with asthma and allergy sensitivities, Mendez said.

"We need to connect the dots between climate change, allergies, asthma and the disproportionate burden of these experienced by Black, Hispanic and Indigenous populations," Mendez said. "Climate change is making allergy seasons longer and more intense. We must do more to reverse these trends."

Extreme heat a factor

Brown is unsure what directly triggered Kingston's latest bout of asthma, although he had experienced a milder attack earlier this year and had been given an inhaler to use twice a day. The family plans to have a lung doctor evaluate him further.

On the days surrounding the asthma attack, the temperatures in northern Georgia had been in the 80s and 90s, and Brown believes that extreme heat and weather are playing a part in his son's condition.

Punishing heat waves from coast to coast and stretching across the globe this summer — part of a pattern of consistently hotter years — can't be ignored, scientists and allergists say.

Rising temperatures elevate ozone levels in the air, which can aggravate asthma symptoms and irritate airways. Intense wildfires are burning more frequently, creating hazardous smoke and airborne particles that affect air quality. Meanwhile, record flooding and rains fueled by warmer temperatures and rising sea levels can spur mold and microbial growth, potentially inflaming a person's asthma.

"It's worse for me on days when it's really hot and humid," said Amanda Ernest, 27, of Boston, who spent several days in the hospital in late June for her asthma. Ernest, who is Black and Haitian American, said she's still unsure what led her to develop breathing problems later in life.

But people of color with a chronic respiratory condition may face added threats that make it harder to breathe.

Recent studies have shown people of color in the U.S., including Black, Latino and Asian populations, are subjected to more polluted air than white Americans, with exposure coming from industrial, agricultural and residential sources. In larger cities, communities of color are more likely to be located in neighborhoods historically overburdened by factories or near highways. And poorer-quality housing in urban areas can be home to asthma triggers, such as mold, cockroaches and mice.

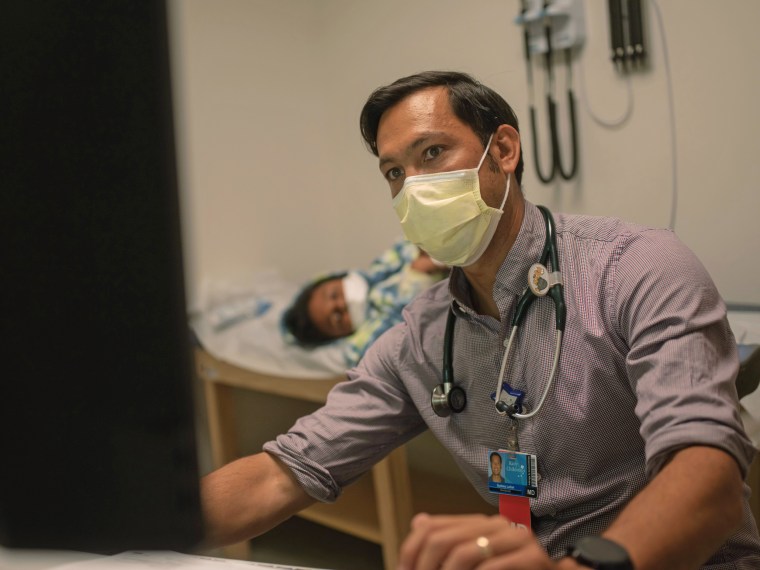

Dr. Sydney Leibel, who treats children with severe asthma at the Rady Children's Hospital in San Diego, said most of his patients come from areas of the city that were historically segregated because of redlining — in which federal agencies in the 1930s allowed for unjust lending practices that disenfranchised Black and Latino home buyers. A study in March in the journal Environmental Science & Technology Letters found that air quality is still worse in cities where redlining was practiced.

"It is children from these areas that are already vulnerable for asthma development and exacerbations that I am most worried about with global warming and the changing climate," Leibel said.

Finding solutions

Leibel's hospital hosts a specialized clinic founded in 2015 with UC San Diego Health, and with financial assistance from the Asthma and Allergy Foundation of America.

Children who are referred to the clinic undergo a thorough evaluation by a pulmonologist, allergist and a clinical pharmacist to determine the severity of their asthma, and to also educate families and offer treatment options.

A study of the program published in 2020 found significant reductions in the number of emergency department visits and hospitalization days for patients who participated in the clinic.

Leibel said the coronavirus pandemic also led to a small reprieve in hospital visits, thanks in part to masking and social distancing.

More than half of the participants at Rady Children's Hospital's asthma clinic are insured by Medi-Cal, California's insurance program for low-income residents.

Giving these most susceptible families a place to go to for controlling their children's asthma is critical, Leibel said.

"Here's the reality: No one has to die from asthma," he said.

On the national level, a study published this year in the New England Journal of Medicine took an unusual approach by conducting a clinical trial involving 1,200 Black and Latino asthma patients in order to understand why there is a persistent racial gap in treatment. The study found that those participants who were also treated with an as-needed inhaled corticosteroid, an anti-inflammatory drug, had a better health outcome — which could ultimately help reduce hospital visits.

Mendez said he's hopeful that the recently passed federal Inflation Reduction Act, which includes hundreds of billions of dollars meant to reduce global warming and lower the cost of prescription drugs, will also be a benefit for asthma sufferers.

"We will continue to advocate for more of these kinds of changes to protect our community," he said, "especially ones that bear this unfair burden of higher hospitalizations and deaths."