Just like you, your dog knows when someone is speaking your native tongue or a foreign language, Hungarian researchers reported.

Brain scans from 18 dogs showed that some areas of the pups’ brains lit up differently depending on whether the dog was hearing words from a familiar language or a different one, according to a report published in NeuroImage.

“Dogs are really good in the human environment,” said study author Laura Cuaya, a postdoctoral researcher at the Neuroethology of Communication Lab at Eötvös Loránd University in Budapest, Hungary.

“We found that they know more than I expected about human language,” Cuaya said. “Certainly, this ability to be constant social learners gives them an advantage as a species — it gives them a better understanding of their environment.”

Dogs appear to recognize their owners’ native language based on how it sounds overall, since the experiments did not use words the dogs would have been familiar with, Cuaya said in an email.

“We found that dogs’ brains can detect speech and distinguish languages without any explicit training,” she added. “I think this reflects how much dogs are tuned to humans.”

Cuaya was inspired to do the research when she and her dog Kun-kun moved from Mexico to Hungary. Cuaya had previously only spoken to Kun-kun in Spanish and wondered if he “noticed that people in Budapest talk a different language,” she said. “Then, happily, this question fitted with the Neuroethology of Communication Lab goals.”

Our results show that dogs learn from their social environments, even when we don’t teach them directly.

Laura Cuaya, Eötvös Loránd University

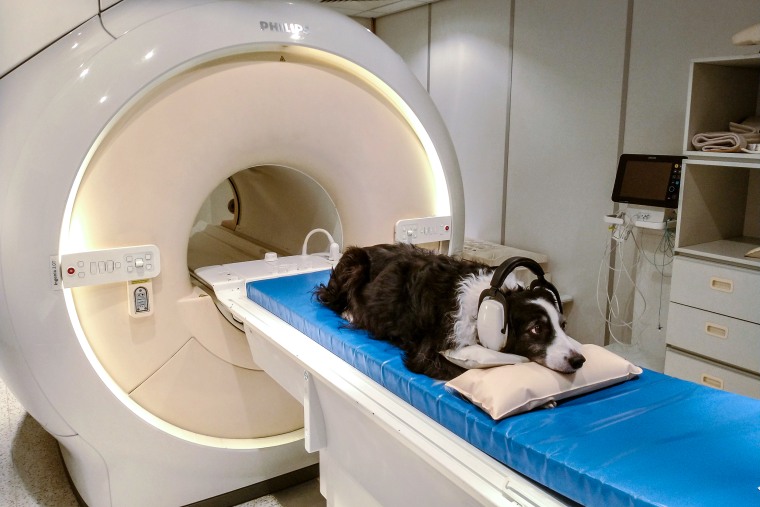

To take a closer look at whether dogs have the same kind of innate ability to differentiate between languages that human infants do, the researchers turned to a group of pet dogs ranging in age from 3 to 11 — five golden retrievers, six border collies, two Australian shepherds, one labradoodle, one cocker spaniel and three of mixed breed — who had previously been trained to remain still in an MRI scanner. The native language of 16 of the dogs was Hungarian and Spanish for the other two.

In their experiments, Cuaya and her colleagues had a native Hungarian speaker and a native Spanish speaker read sentences from Chapter 21 of “The Little Prince” while the dogs were in the scanner. The text and the readers were unknown to all the dogs.

When Cuaya and her colleagues compared the fMRI scans from the readings in the two languages, the researchers found different activity patterns in two areas of the brain that have been associated in both humans and dogs with deciphering the meaning of speech and whether its emotional content is positive or negative: the secondary auditory cortex and the precruciate gyrus. The differences were more pronounced in older dogs and dogs with longer snouts.

Cuaya suspects the older dogs had a different result because they had more years listening to the native language of their owners. She wasn’t sure why dogs with longer snouts did better at distinguishing the languages.

What should owners take from this study?

“As many owners already know, dogs are social beings interested in what is happening in their social world,” Cuaya said. “Our results show that dogs learn from their social environments, even when we don’t teach them directly. So, just continue involving your dogs in your family, and give them opportunities to continue learning.”

The findings were a surprise to Dr. Katherine Houpt, the James Law Professor Emeritus in the section of behavior medicine at the Cornell University College of Veterinary Medicine.

“I didn’t know that they would respond differently to different languages, particularly because I thought voice intonation would mean more than the words,” Houpt said. “This shows they know when you are not speaking the language they learned. Knowing the difference between languages might be important to dogs as part of their guard dog duties. [When on alert] the dog is more likely to be suspicious of people speaking a different language.”

“To me the most interesting thing is that older dogs and long-nosed dogs understand better,” Houpt said.

It’s possible, she added, that the explanation for longer-snouted dogs might be that head shape is common among sheep dogs, who have to be able to understand what a shepherd is saying to the dog.