Starting treatment for multiple sclerosis early — before symptoms even begin — could possibly delay the onset of the condition, new research finds.

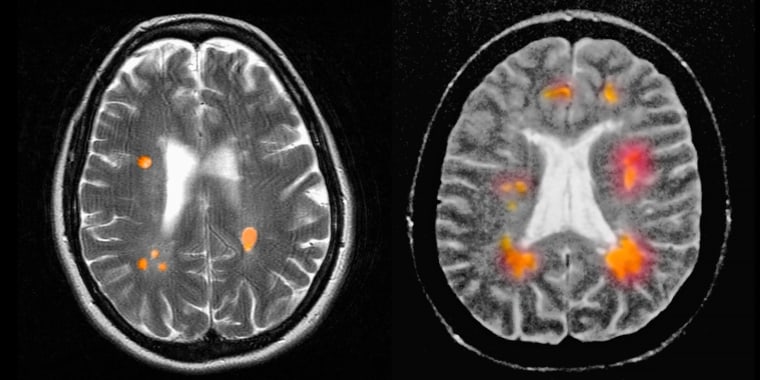

Preliminary results of a small Phase 3 clinical trial showed a drug called teriflunomide may delay or prevent MS symptoms in people who have what’s known as radiologically isolated syndrome, which causes the same brain and spinal cord lesions seen in people with MS. The findings will be presented next week at the American Academy of Neurology’s 75th annual meeting in Boston.

About half of people who have RIS go on to develop MS.

“The goal of treatment in the RIS phase is to keep a patient in the 50% that doesn’t convert to MS in 10 years, to stop it before the disease becomes symptomatic,” said Dr. Orhun Kantarci, a neurologist at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, and a co-author of the new study.

There are currently no Food and Drug Administration-approved treatments for RIS, but early intervention is crucial, experts say.

“Once damage starts to accumulate and disability starts to develop, we can’t reverse that,” said Dr. Jeffrey Cohen, a neurologist at Cleveland Clinic who was not involved in the research. “So it’s very important to prevent it from happening in the first place.”

MS is a central nervous system disease, affecting the brain and the spinal cord. It can cause a number of symptoms that vary in severity, including vision problems, muscle weakness, numbness and difficulty concentrating, according to the National Institutes of Health.

People with RIS may have very subtle symptoms that go unnoticed, said Dr. William Shaffer, a neurologist at UCHealth in Fort Collins, Colorado, who was also not involved in the trial. Early treatment could prevent any progression as soon as lesions are detected, he said.

The drug teriflunomide, sold under the name Aubagio, is already approved to treat patients with the most common type of MS, called relapsing-remitting MS. It accounts for 85% of all cases. Sanofi, which makes the drug, helped fund the trial.

The new trial is the second to test whether an approved MS drug is able to prevent symptoms in people who have RIS. The ARISE trial tested another MS drug, called Tecfidera, in 87 people in the U.S. and found it to be effective at delaying or preventing MS symptoms.

The latest study included 89 adults from Europe and Turkey with an average age of 40 who were followed for two years. Seventy percent were female, and all had RIS lesions that showed up on an MRI, but none had symptoms of MS.

Compared to those who got a placebo, those who were treated with teriflunomide had a 63% decreased risk of developing early symptoms of MS, including numbness and tingling and issues with balance or dizziness.

“The medications seem to work better when they’re started earlier,” Cohen said.

Although the trial only lasted two years, Kantarci said this is consistent with how long drugs are studied in clinical trials for MS, and the findings still suggest long-term results.

Who should get early treatment for MS?

Although early intervention is expected in other diseases that can show up on scans before they cause symptoms, such as breast and colorectal cancers, that isn’t the case for MS, Kantarci said.

But unlike breast and colorectal cancer, people aren’t screened for RIS; it’s typically found incidentally when people have a brain or spinal MRI for other reasons. Kantarci doesn’t think that should change; RIS is rare and doesn’t warrant routine screening, he said.

What’s more, because only half of patients with RIS go on to develop MS, early treatment would be unwarranted in the other half.

“Therapies have side effects and have some risks associated with them like all medications, and they’re expensive,” said Dr. Nancy Sicotte, director of the Multiple Sclerosis and Neuroimmunology Center at Cedars-Sinai in Los Angeles.

A better understanding of RIS could help guide doctors to which patients would benefit most from early intervention.

Previous research has already identified some specific lesions in RIS patients that appear to indicate a person will go on to develop MS. In the future, Sicotte said, early intervention may be reserved for these patients.

Kantarci agreed.

Based on previous studies, “we know that some patients are more likely to become symptomatic with MS, including those who are younger or who have problems with their spinal fluids and spinal cord that suggest MS,” he said. “We’d like those to be the ones who receive the treatment.”

Follow NBC HEALTH on Twitter & Facebook.