Visits to emergency rooms for traumatic brain injuries — most of them concussions — jumped a whopping 29 percent in just four years, according to new research that suggests a growing awareness of the seriousness of these injuries.

Highlighting the danger, a second study published Tuesday in the Journal of the American Medical Association found that college football players, especially those who had been diagnosed with concussions, appeared to have atrophy in a brain region vital to creating new memories.

Researchers can’t say whether the rise in ER visits from 2006 to 2010 comes from an increase in concussions, greater awareness of their dangers, more vigilance on the part of doctors making the diagnosis or a combination of those factors, said Dr. Jennifer R. Marin, the study’s lead author and an assistant professor of pediatrics and emergency medicine at the University of Pittsburgh Medical School.

But brain injury experts said the biggest factor was probably a growing public awareness of their impact — and that they don’t only affect professional athletes.

"It’s not just boxers or pro football players. It can be your kid.”

“We’ve known that there were problems with boxers’ brains since 1928, but boxing was historically viewed as a uniquely brutal sport that had to be different from football,” said Dr. Douglas Smith, a professor of neurosurgery and director of the Center for Brain Injury and Repair at the University of Pennsylvania Medical Center. “Next, people started thinking that football might be like boxing, but only at the pro level where there are big guys crashing into one another. Now we realize that kids can have the same issue. It’s not just boxers or pro football players. It can be your kid.”

In fact, the biggest jumps in ER visits for traumatic brain injury were among toddlers and seniors.

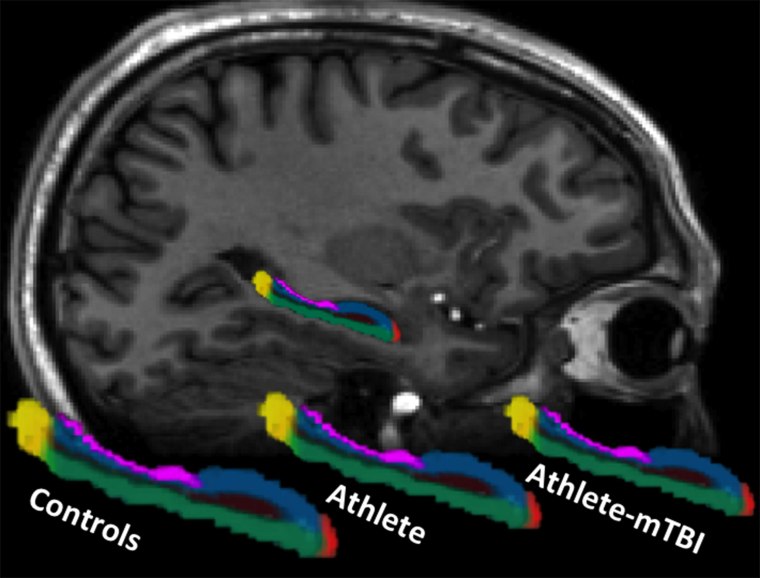

In the second study, researchers scanned the brains of 25 college football players who had had a concussion, 25 players without concussions and 25 students who did not play football.

The researchers focused on the hippocampus, an area of the brain that is crucial to forming new memories and that has been found to be atrophied in boxers and pro football players who have developed chronic traumatic encephalopathy, or CTE.

Overall, football players had smaller hippocampi than those who played no football. But the most striking results were in players who had been diagnosed with concussions, said co-author Patrick Bellgowan, an associate professor and director of cognitive neuroscience at the Laureate Institute for Brain Research.

The findings were “dramatic,” said David Hovda, a professor of neurosurgery at the University of California, Los Angeles, and director of the UCLA Brain Injury Research Center. But no one knows whether the atrophy is due to “the concussion itself or if the atrophy could have been caused by mismanagement of the player after injury,” he added.

As for the atrophy seen in players with no diagnosed concussions, Hovda suggested it could be due to sub-concussive blows, brain-rattling hits that aren’t hard enough to cause actual concussion symptoms.

Researchers also don’t know whether the atrophy is permanent, Hovda said.

“We know that the brain atrophies with age, so it would be interesting to know if this TBI-induced atrophy would stay ahead of the curve.”

"The question for parents is, do you want to take that risk to the brain so your kid can be a teenage superstar and then spend the rest of his life dealing with what’s left?"

How big a deal is the loss of some hippocampal volume?

“I know I use every neuron I have,” Hovda said. “So any atrophy would be significant. What we do not know is to what extent the atrophy is clinically relevant.”

The shrinking of the hippocampus is “alarming,” Smith said.

“This is another nail in the coffin for contact sports. It’s another topic to bring up over the dinner table when kids are trying out. The question for parents is, do you want to take that risk to the brain so your kid can be a teenage superstar and then spend the rest of his life dealing with what’s left?”

The rise in ER visits might be good news, Bellgowan said, if it is a sign that Americans are learning that concussions shouldn’t be ignored.

A lot of parents still brush off concussions when kids don’t appear to have severe symptoms. Bellgowan would like to see parents take their kids to a concussion specialist no matter how slight the jolt to the head might seem at the time. Symptoms can linger or even get worse if concussions aren’t managed properly, he said.

“One message we’re hoping to get out is that if a kid gets hurt, parents should bring him in to see a specialist,” Bellgowan said. “This needs to be taken seriously because it may have long-term consequences.”