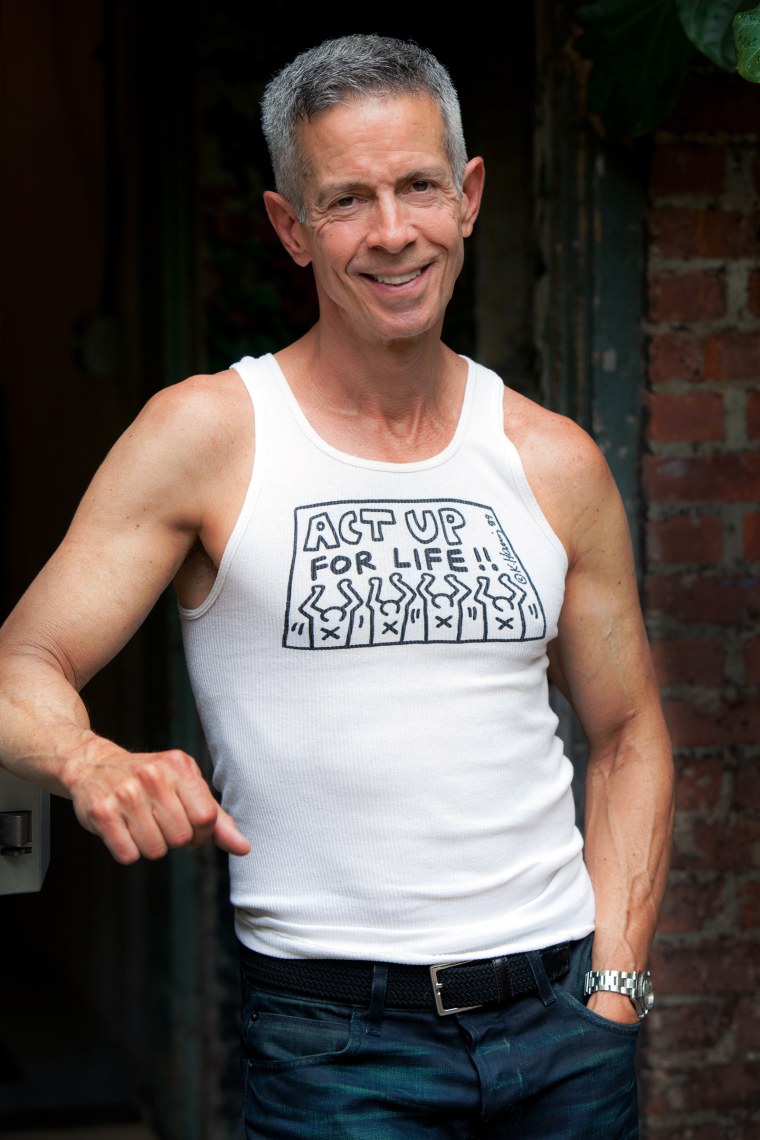

Peter Staley was at the top of his game when AIDS took off in New York City in the 1980s. He was a Wall Street bond trader and didn’t think the rumor about a disease affecting gay men was anything he needed to worry about.

He certainly never could have predicted that it would consume his life.

“I was a closeted gay man,” Staley, 55, told NBC News. “I was completely disconnected from the established but mostly closeted gay community that existed in New York that was doing the early struggling against this new epidemic.”

Now the HIV pandemic is more than 30 years old, and a new study out this week has put what one expert calls the final nail in the coffin of the idea that a single flight attendant carried HIV across the U.S. Instead, the study shows the virus probably arrived in New York City from the Caribbean around 1970, spreading to San Francisco in 1976 and then to the world.

Related: Genetic Study Shows HIV Came to New York in 1970

The report clears the name of Canadian Gaetan Dugas, who died in 1984 after helping Centers for Disease Control and Prevention investigators track down HIV.

“It’s shocking how this man’s name has been sullied and destroyed by this incorrect history. He was not ‘Patient Zero’ and this study confirms it through genetic analysis,” said Staley, who is currently teaching political activism at the Institute of Politics at Harvard’s John F. Kennedy School of Government.

Many Americans expressed horror at the image of an attractive, young, gay flight attendant flying around the world spreading a deadly virus through hundreds — by his own description — of sexual liaisons. The case cast the HIV epidemic even more strongly as a punishment for what many viewed as a sinful lifestyle.

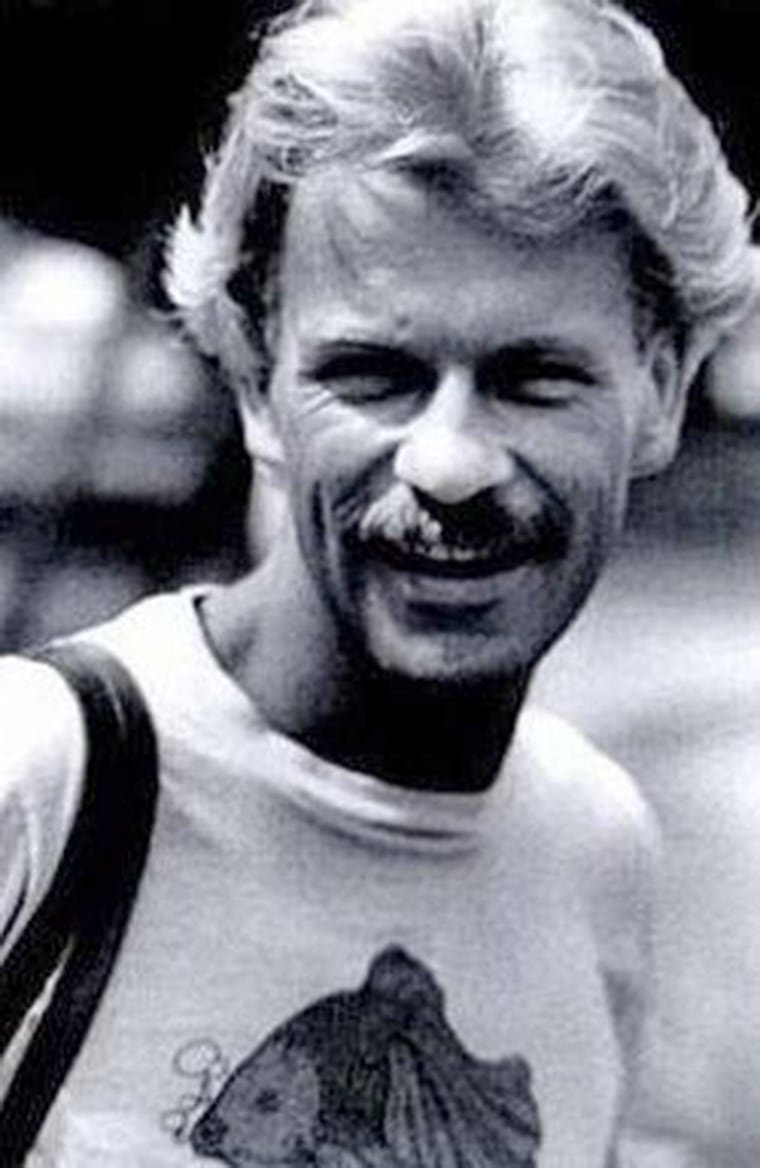

Sean Strub isn’t surprised by the findings. Strub, who founded POZ magazine, is another survivor of the early AIDS epidemic who understands the stigma then and now has little to do with scientific reality.

“The neglect and the governmental indifference started long before the epidemic was recognized,” Strub told NBC News.

From then-President Ronald Reagan on down, no one sounded an alarm about a surge in deaths from a mysterious infectious disease. Reagan's press secretary Larry Speakes openly joked about it.

The nonchalance allowed the epidemic to fester.

“It didn’t set off any alarm bells to a young closeted gay man in New York in 1983. And for that I am furious,” Staley said. “I mostly likely became infected that summer.”

Staley studied political activism on the streets.

“America was just letting thousands of its citizens die because of bigotry and hatred,” Staley said.

“America was just letting thousands of its citizens die because of bigotry and hatred."

Strub and Staley both learned they were HIV positive in 1985. “I found out right after Rock Hudson died,” Staley said. “There were panics going on. Rumors would appear that a child had HIV in a school system and parents would pull their kids out of the school.”

Related: Actor Rock Hudson's Death Shifted AIDS conversation

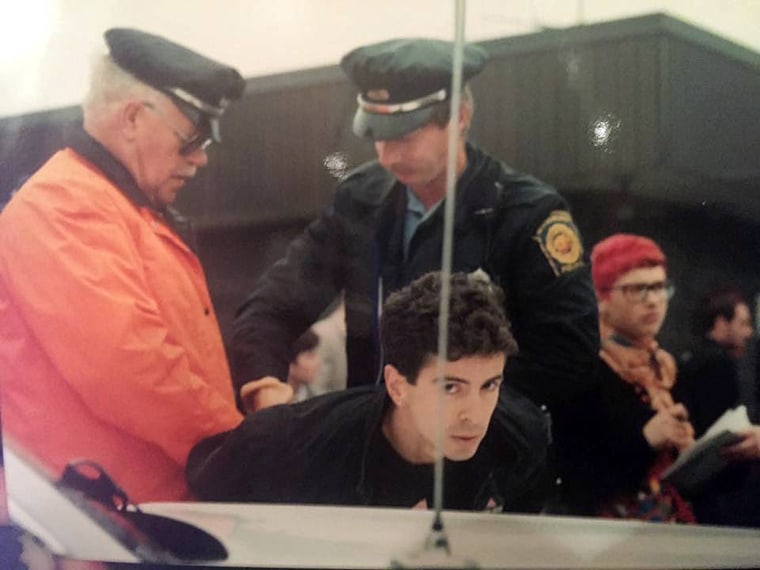

Staley at first worked as a bond trader by day and an activist by night. He joined a new group called the AIDS Coalition To Unleash Power (ACT UP) but got sicker and sicker and finally quit his job.

“The next week, I got arrested. I did my first demo with ACT UP,” Staley said. "I got 10 arrests during my time in ACT UP. We became the movement of our age. We became the Occupy, the Black Lives Matter of the 80s.”

They shut down the New York Stock Exchange and covered the home of North Carolina senator Jesse Helms with a giant condom.

The articulate, passionate and highly educated leaders of groups such as ACT UP forced a change in U.S. policies and transformed the research agenda. “By 1990, the NIH (National Institutes of Health) was spending over a billion dollars a year on AIDS research,” Staley said. “We guilt-ripped the whole country into finally reacting.”

Now there are more than two dozen HIV drugs. While there’s no cure for HIV, cocktails of these drugs can control it almost completely, and they’ve been reformulated into once- or twice-a day pills. People who take them can control the virus so well they almost never infect anyone else.

Related: Daily Pills Protect People Against HIV

Strub was pulled back from the brink himself, with a ravaged immune system and covered with lesions from Kaposi’s sarcoma, when researchers learned they could combine HIV drugs for powerful effect in 1996. It transformed the world for HIV patients, who no longer faced certain death.

“Most of us didn’t think we’d live to see the fruit of our activism,” Staley said.

“While we have incredibly effective medical treatments, we don’t have a pill to cure stigma."

HIV research has gone mainstream and work on a vaccine gets funding and attention. But Strub and Staley say their fight is far from over.

“While we have incredibly effective medical treatments, we don’t have a pill to cure stigma,” said Strub, who is 58. “And HIV-related stigma is worse today than it has ever been.”

Now Strub fights against criminalization of HIV patients as director of The Sero Project.

“Today, with disclosure, you risk losing your job. You risk partner violence. Women fear disclosing for fear of losing her children,” said Strub.

Strub’s group fights laws that make it a crime for an HIV-positive person to have sex with anyone without disclosing it — laws they say that have been abused by angry ex-partners, who can accuse HIV patients who have no way of proving whether they disclosed.

These laws, and a continued high level of discrimination among the general public, have driven the HIV epidemic underground, Strub says. People resist getting tested for fear of being prosecuted later. “The evidence is these laws are harming public health,” he said.

“Infections are at an all-time high among gay men,” he added. “The rates are rising among young gay men of color.” Statistics from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention confirm this.

“Today, with disclosure, you risk losing your job. You risk partner violence."

The CDC reports that, at current rates, one in six men who have sex with men will be diagnosed with HIV in their lifetimes. Gay and bisexual men in Southern cities are at the highest risk.

“We are not surrounded with the same kind of death and dying that was such a part of our daily lives. But that has helped erase it from the public’s consciousness,” Strub said. “It isn’t fashionable any more. But it is still very much a crisis. And many communities have been utterly neglected.”

Related: Gay, Bisexual Black men have 50 Percent HIV Risk

Staley says the worsening political divide in the United States has taken the epidemic in new directions. “The stigma is as bad as ever,” he said. “I call it Red AIDS and Blue AIDS.”

In mostly Democratic areas of the country — large cities in the Northeast and California — state health departments are pushing widespread HIV testing and treatment that have pushed new infections down.

Staley said Washington, D.C., has seen a 40 percent drop in the past decade, while San Francisco has seen a 50 percent drop in the past decade.

“It is back like the 1980s again, where apathy and ignorance and stigma are just letting the epidemic rage on."

“In these blue areas of the country that are using the current scientific tools, we are seeing great progress. It is the red areas, especially the deep South, where the epidemic is either flat or getting worse,” he said.

Related: Southern, Urban Gay Men More Likely to Have HIV

Republican-led states have fought some of the innovations proven to slow the spread of HIV and other infections. For instance, Indiana bans needle exchanges, although last year Gov. Mike Pence, a Republican now running for vice president, issued an executive order allowing temporary needle exchanges after an outbreak of HIV among injecting drug users in his state.

Related: CDC Says Urgent Action Needed in Indiana

“It’s frustrating when you have these tools and large parts of the country are not using them at all,” Staley said. “Lives are being lost because we just don’t have the money and the political will to make it work.”

In the United States, more than 1.2 million people have HIV, and about 50,000 people are newly infected each year.

“It is back like the 1980s again, where apathy and ignorance and stigma are just letting the epidemic rage on,” Staley said. “I am an AIDS activist still and trying to finish the job we started in the late 1980s.”