A dangerous strain of antibiotic-resistant bacteria is far more common in Houston than anyone knew and shows signs it can spread prolifically, researchers reported Tuesday.

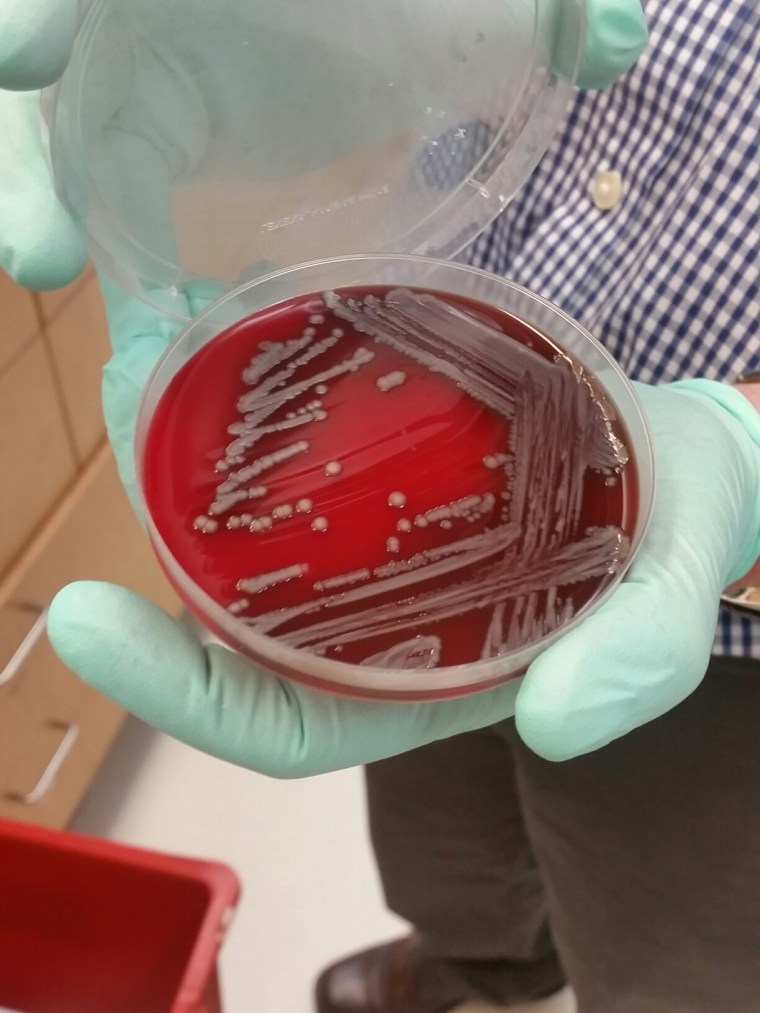

It’s a specific strain of a bacteria known as Klebsiella pneumoniae. The superbug is showing a special talent for picking up genes that give it the ability to resist a broad range of antibiotics, the team at Houston Methodist hospital system said.

“It causes very serious infection in hospitalized patients,” said Dr. James Musser, who led the study team.

“What we discovered, surprisingly, is one of the major strains causing infection in our patients in Houston is genetically distinct from strains of this same germ causing human infections [elsewhere] in the United States,” Musser added.

Related: Here's Why A New Superbug is Scaring Scientists

Doctors and public health officials have been warning for years about the rise of drug-resistant superbugs. They are especially dangerous to patients in the hospital for extended periods of time but they can also be found in people with ordinary infections such as cystitis and pneumonia.

There have been some nightmarish outbreaks — like one in 2011 at the flagship National Institutes of Health’s clinical center in Bethesda, Maryland, that killed seven people. That outbreak was caused by a strain of Klebsiella resistant to a major class of antibiotics called carbapenems.

Officials eventually discovered it was breeding in the hospital's sinks.

Related: Gene-Swapping Bacteria Make New Superbugs

And just this past January, doctors reported on the case of a Nevada woman who had traveled to India and died from a rare superbug that could not be killed by any antibiotic available in the U.S.

Musser's team did an extended genetic analysis of 1,777 Klebsiella samples taken from patients at the 2,000-bed Houston Methodist hospital system between 2011 and 2015.

"Currently, unfortunately, there is no approved human vaccine against Klebsiella pneumoniae."

They found all sorts of tricks the bacteria had developed to resist antibiotics. That included plasmids — little cassette-like pieces of genetic material that different species of bacteria can swap. They are a very quick and easy way for bacteria to acquire resistance genes and are very worrying to infectious disease experts.

“We identified 15 strains expressing the New Delhi metallo-beta-lactamase-1 (NDM-1) enzyme that confers broad resistance to nearly all beta-lactam antibiotics,” the team reported in the journal mBio, published by the American Society for Microbiology.

These extended-spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL) genes are especially dangerous and often kill patients.

A once-rare strain of ESBL Klebsiella called CG307 was unusually common, they found. That may mean there’s more to come, the team warned.

Related: Feared Superbug Gene Showed Up in 2015

“Our results may portend the emergence of an especially successful clonal group of antibiotic-resistant K. pneumoniae,” they concluded.

In other words, bacteria are actively trading a toolkit that makes them both deadly and resistant to treatment. The discovery in Houston, a diverse city of 6 million people that’s also a popular destination for people seeking medical treatment, is especially troubling, the researchers noted.

The superbug is still around, by the way. "We confirmed that CG307 strains continue to be an abundant cause of infections in our hospital system by sequencing an additional 96 ESBL-producing K. pneumoniae strains recovered in 2017," the team wrote.

“Currently, unfortunately, there is no approved human vaccine against Klebsiella pneumoniae,” Musser said. “We desperately need to have a human vaccine.”