Emet Oden tried reaching out in the only way he knew how.

“I had been struggling with my mental health and, specifically, suicidal thoughts since the eighth grade,” said Oden, who is now 18.

“I didn’t want to talk to my friends about it, because they never knew how to handle it. I just didn’t want to bother them.”

He dropped heavy hints around some teachers he trusted, but they didn’t pick up on the cues.

“I was kind of hunched. Walking around, I just looked sad,” said Oden, who’s about to graduate from his high school in Nashville.

When a teacher asked him how he was doing, he answered that he was fine, while wishing that someone would press a little deeper. But no one did.

Oden attempted suicide a little over a year ago. He’s part of a growing number of teens and children who are thinking about or even attempting suicide.

A new study out Wednesday finds that more kids are either thinking about or attempting suicide.

“When we looked at hospitalizations for suicidal ideation and suicidal encounters over the last decade, essentially 2008 to 2015, we found that the rates doubled among children that were hospitalized for suicidal thoughts or activity,” Dr. Gregory Plemmons of Vanderbilt University told NBC News.

Plemmons and colleagues analyzed a database of visits at 49 children’s hospitals for kids aged 5 to 17.

Although suicide ideation — thinking about suicide — and suicide attempts accounted for just 1 percent of all hospital visits, the numbers have steadily increased,

Half of the encounters involved teens aged 15 to 17; 37 percent were 12 to 14; and almost 13 percent were children aged 5 to 11 years. Girls made up nearly two-thirds of the cases.

That’s at the same time that actual suicide deaths are up, too, so it’s not a case of awareness alone, the researchers said.

It’s possible pediatricians are paying more attention and sending kids to specialist hospitals because they don’t feel equipped to deal with suicidal thinking, Plemmons and colleagues reported in the journal Pediatrics.

“I don't have any one magic answer that explains why we're seeing this,” Plemmons said. “We know that anxiety and depression are increasing in young adults as well as adults. I think some people have theorized it's social media maybe playing a role, that kids don't feel as connected as they used to be.”

But there was a hint in Plemmons’ data. The rate of hospital visits was much higher during the school year.

“On average, during the eight years included in the study, only 18.5 percent of total annual suicide ideation and suicide attempt encounters occurred during summer months,” the team wrote.

“Peaks were highest in fall and spring. October accounted for nearly twice as many encounters as reported in July.”

Dr. Laurel Williams, chief of child and adolescent psychiatry at Texas Children’s Hospital, says mental illnesses such as depression, mood disorders and even bipolar disease may play a role.

“Over 90 percent of young people that eventually go on to commit suicide have some diagnosable mental health disorder,” she said.

“A young person has a mental health problem, let’s say depression. Then an external stressor, let’s say at school or at home, will push them over the edge.”

Pressures of social media

Oden said he had been struggling for some time, and was hospitalized three times for what’s called suicide ideation — not just thinking about suicide, but actively planning for it. “There were family issues and the pressure of school because I was really behind after being a hospital inpatient,” he said.

“There was a lot going on.”

Williams said that’s a common theme — teens and young adults feel pressure, with no time to break off and connect with someone.

"It doesn’t matter what it is, if it makes you feel hopeless, it makes you feel hopeless."

Oden, a transgender male, had been cutting himself. Self-harm is one red flag for suicide risk, although not every child who cuts or scratches or harms him or herself is at risk of suicide.

Social media complicated things.

“I could go onto tumblr and in the search engine search type ‘depressed’ and see all these posts of people experiencing depression,” he said. “It validated what I was feeling, but I also felt trapped there.”

And then there were classic feelings of worthlessness. “I felt I was annoying and people would be better off without me,” he said.

That’s familiar to Dese’Rae Stage, a suicide attempt survivor and activist who photographs and tells the stories of suicide survivors as part of the Live Through This project.

She can’t really remember her first suicide attempt, at age 16 or 17, but she remembers the second time. She was 23 and in a tumultuous relationship.

“I was thinking ‘I am never going to have a good relationship. I am never going to have a good job. I am never going to …’,” she said. “I had just gotten into a Ph.D program. I had a future and I just couldn’t see it.”

Many of the people Stage has interviewed describe feelings of despair and being unable to connect with the people nearest to them.

“I think that is where people get confused about the suicidal experience,” Stage said.

“You can tell people all day long that they have this future and they can’t see it. It doesn’t matter how surrounded by people you are. You feel so isolated and alone.”

Stage is not sure if social media has made things better or worse.

“To me, the internet is probably the most wonderful thing that ever entered my life,” she said. “But at 35, I know what my boundaries are. I know what is going to make me feel bad if I look at it.”

Children and teens may get overwhelmed by the constant pressure to post, to show only the positive.

“Maybe they haven’t figured out how to balance in-person social connection with the internet social connection,” Stage said. “We can use technology in good and bad ways and we can just do life in good and bad ways.”

What she can understand is why suicide is such a risk for pre-teens and teens.

“I think that life as a teenager is even harder than life as an adult. When you are a teenager, you are feeling things for the first time,” she said. “You don’t know how you are going to solve that problem, whatever it might be. It doesn’t matter what it is, if it makes you feel hopeless, it makes you feel hopeless,” she said.

Stage remembers music was so much more important to her as a teen. “Every lyric would touch me and I would feel it so deeply.”

"There is this fear that if you talk about suicide or you talk about depression that sometimes somehow you'll encourage a kid to do that. We know that that's not the case."

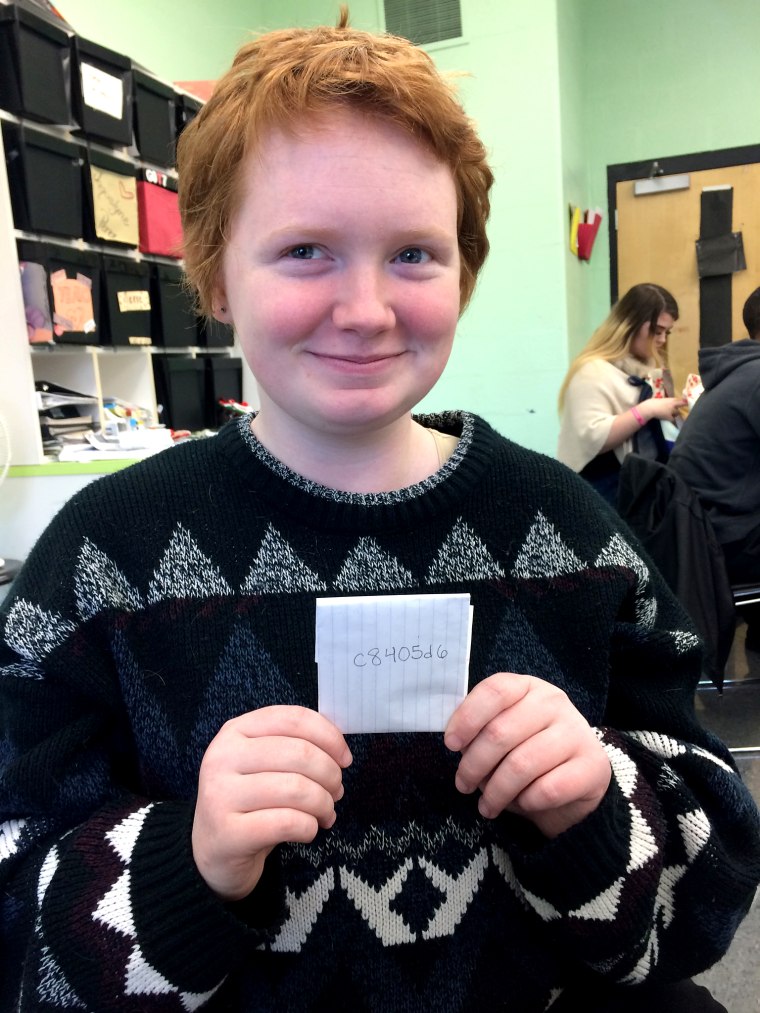

Oden, who volunteers at the Tennessee Suicide Prevention Network, said people may not take the time to listen to someone in distress.

“Teens, many of us, we don’t know how to listen, like truly listen to someone and be there for someone,” he said. “We just want to fix the problem. Listening to someone is the most important part.”

In the end, Oden’s pastor helped, by simply listening. For Stage, the help was more traditional, with regular therapy and medication. Now she’s married and has a four-month-old son. Oden is preparing to head to college at the University of Louisville.

Look for the signals

“If someone is sending you invitations and you see those warning signs, just ask them point blank if they are suicidal,” Oden advised.

“That can be so, so difficult because there is this fear that the person will get mad at you or they will react in a bad way. But most suicidal people want that connection. Being asked is such a relief.”

Williams agreed. “You should always ask. If you are concerned or have a suspicion you should always ask,” she said.

It doesn’t give people ideas they didn’t have before, Plemmons said.

“I think there is this fear that if you talk about suicide or you talk about depression that sometimes somehow you'll encourage a kid to do that,” he said. “We know that that's not the case.”

Parents, teachers and friends can all help, he said.

“Talking to your kids about it's OK to be mediocre, it's OK to fail once in a while, and share experiences of your own feelings,” he advised.

“I think it's really important to limit screen time whenever possible,” he added.

“Studies show that if someone is spending an inordinate amount of time on electronics or screen time, that does seem to be associated with increased rates of depression so paying attention to how much time I think your kids are utilizing social media, or computers, and things like that, I think is important too.”

Editor's note: If you are looking for help, please call the National Suicide Prevention hotline at 1-800-273-8255.