New York Gov. Kathy Hochul declared a state of emergency on Friday in response to poliovirus, which has been detected since April in wastewater from four counties plus New York City.

Just one case has been confirmed — an unvaccinated man in his 20s who was diagnosed with paralytic polio in Rockland County in July. But one paralytic case is usually a sign of hundreds of additional infections, since only around 1 in 100 polio infections result in serious disease, according to New York's declaration.

Nassau County was the latest to find polio in its wastewater. The poliovirus found in a sample collected there in August was genetically linked to the paralytic case. The viruses found in another 50 samples collected from Rockland, Orange and Sullivan counties share the same genetic link.

State health officials said this is evidence that polio is spreading in these communities.

Polio vaccination rates are low in most of the affected counties: In Orange County, around 58% of children have received three shots before their second birthday. Rockland County has a rate of 60%, and Sullivan County has a rate of 62%. The vaccination rate in Nassau County is similar to the New York state average: around 79%.

By declaring a state of emergency, New York hopes to raise the state average above 90%.

"On polio, we simply cannot roll the dice,” New York State Health Commissioner Dr. Mary Bassett said in a statement. “If you or your child are unvaccinated or not up to date with vaccinations, the risk of paralytic disease is real. I urge New Yorkers to not accept any risk at all."

With the emergency declaration, health officials aim to expand the network of people who can administer polio vaccines to include emergency medical services workers, midwives and pharmacists. It also requires health care providers to send data about polio vaccinations to the state health department so the department can determine where to focus its vaccination efforts.

Polio vaccines are 99% effective against paralytic polio, which can be fatal in 2% to 10% of cases.

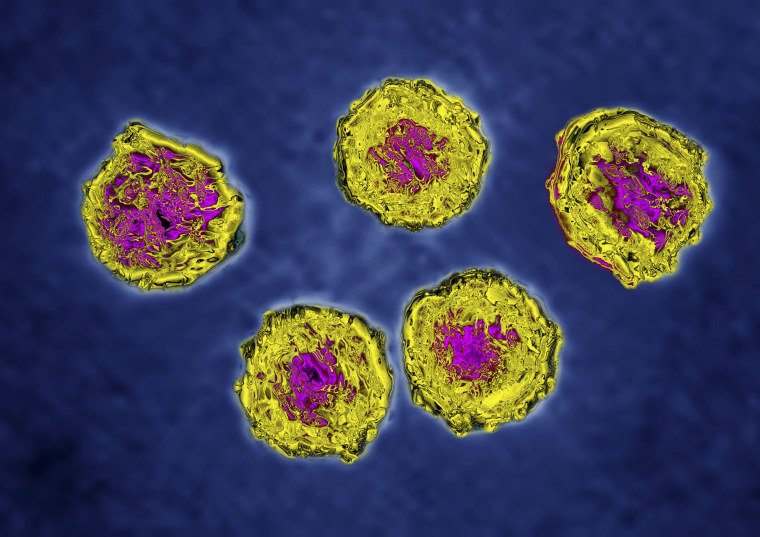

The person in New York who developed paralytic polio was infected with vaccine-derived polio, a strain linked to weakened, live virus from an oral polio vaccine that’s not administered in the U.S. This type of polio can arise after people take the oral vaccine then briefly shed the virus in a community with a low vaccination rate. The virus can then spread among unvaccinated people and mutate to be more virulent.

The types of poliovirus found in New York City’s wastewater samples have not been genetically linked to the paralytic case but are known to cause illness. As of June, 86% of children in New York City between the ages of 6 months and 5 years had gotten three doses of the polio vaccine.

Most Americans receive four doses of the vaccine between the ages of 6 weeks and 6 years old.

People who have not started their vaccination series by age 4 should receive three doses, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Those who have only received one or two shots should complete their vaccination series as soon as possible.

If you're unsure whether you've been vaccinated, the CDC suggests asking parents or caregivers, doctors or health clinics you visited as a child, or previous schools or employers that required immunizations. Most state health departments also allow you to request childhood vaccination records, though many immunization registries are fairly new and do not carry records for older adults.

The CDC says it's safe to repeat vaccinations if you can’t find your records.